Articles are given in chronological order by date of publication. Those marked with an asterisk (*) indicate principal publications, mostly on sites and monuments that have been introduced to the scholarly world for the first time.

ABBREVIATIONS:

BAI: Bulletin of the Asia Institute (Bloomfield Hills, Michigan)

ISSN: 0890-4464

BSOAS: Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London (Cambridge University Press)

ISSN: 0041-977X EISSN: 1474-0699

Available by subscription from Cambridge Journals Online

EI3: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Third Edition (E. J. Brill, Leiden-Boston)

ISSN: 1873-9830

Available on the Encyclopaedia of Islam website, http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/browse/encyclopaedia-of-islam-3

EIr: Encyclopaedia Iranica (Columbia University, New York)

ISSN 2330-4804

Available on the Encyclopaedia Iranica website, www.iranicaonline.org

JRAS: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (Cambridge University Press)

ISSN: 1356-1863

Available by subscription from Cambridge Journals Online

MHJ: The Medieval History Journal, Journal of the Medieval History Society (Sage Publications, New Delhi - Thousand Oaks - London)

ISSN: 0971-9458

Available by subscription from Sage Online: http://mhj.sagepub.com

SAS: South Asian Studies, Annual of the British Association for South Asian Studies (formerly Society for South Asian Studies), the British Academy (Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group)

ISSN: 0266-6030

UDS: Urban Design Studies, Annual of the University of Greenwich Urban Design Unit (Araxus, London. www.araxus.org)

ISSN: 1358-3255

“The City of Turquoise, a preliminary report on the town of Hisar-i Firuza”, M. and N. H. Shokoohy, Water and Architecture, AARP Environmental Design, II, Rome, 1985, pp. 82-9, 3 maps and architectural drawings, 5 photographs.

“The City of Turquoise, a preliminary report on the town of Hisar-i Firuza”, M. and N. H. Shokoohy, Water and Architecture, AARP Environmental Design, II, Rome, 1985, pp. 82-9, 3 maps and architectural drawings, 5 photographs.

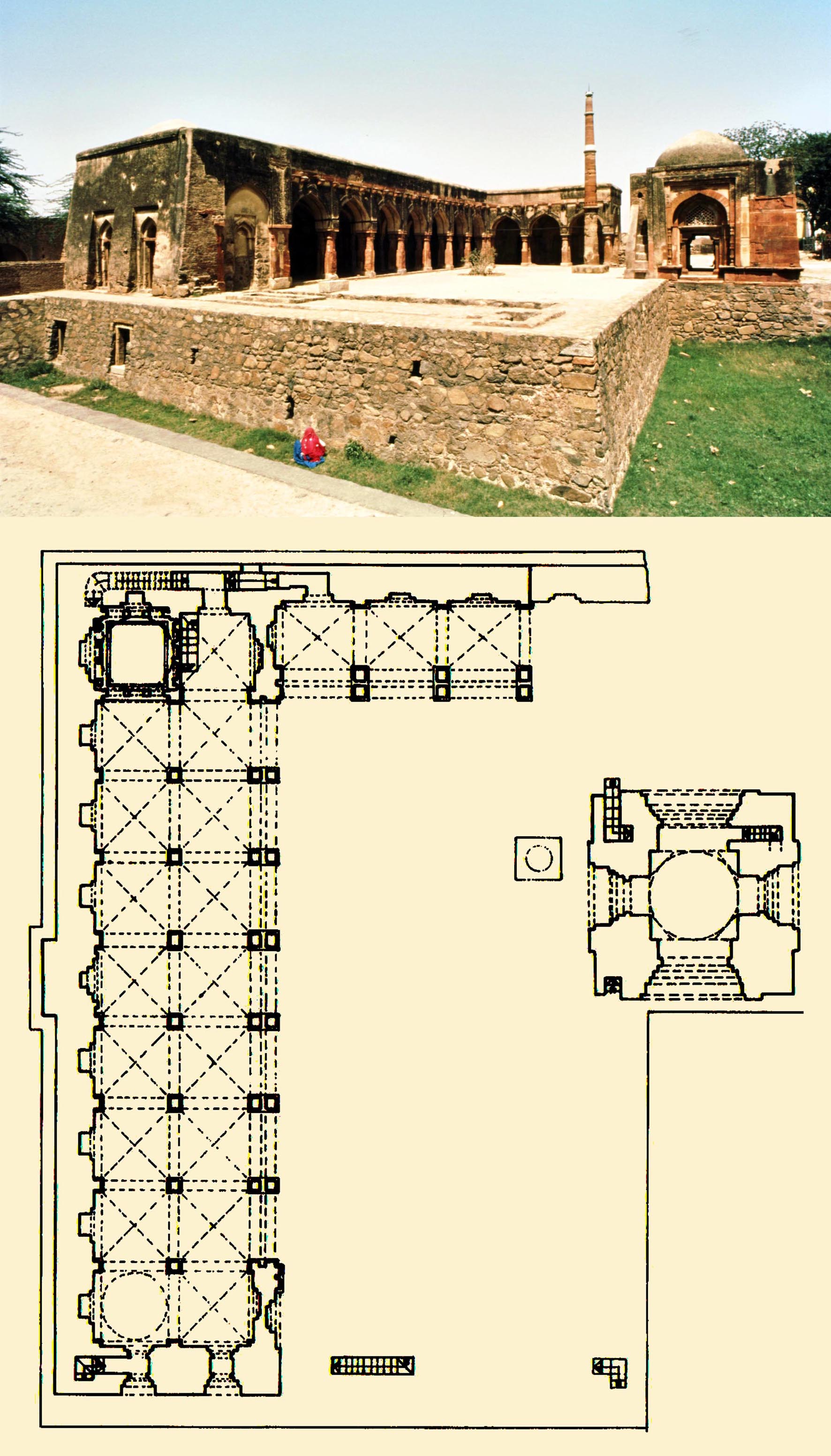

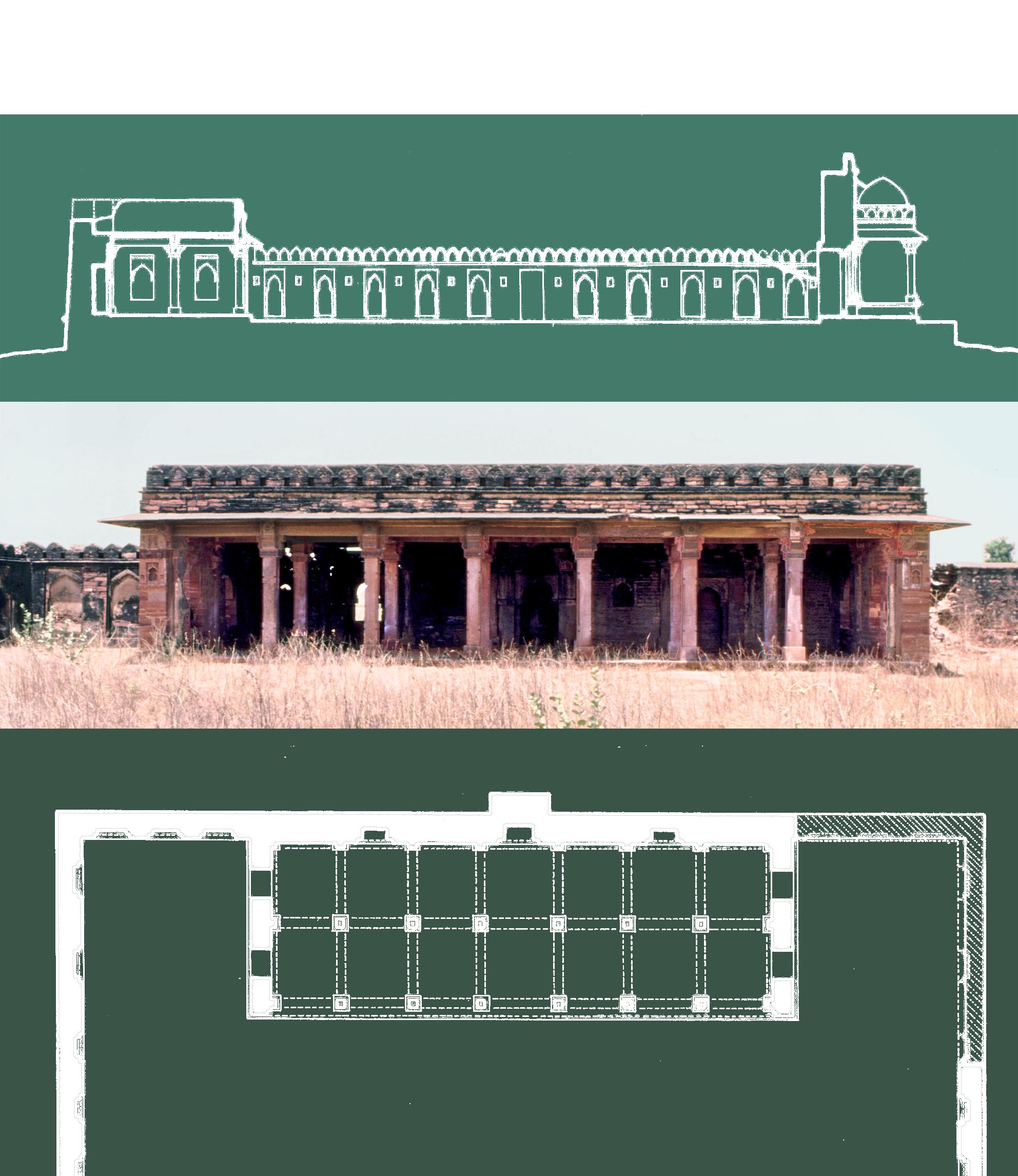

A brief introduction to the site of Hisar, unfamiliar at the time to many in the field, was published three years before the final report. The paper includes a plan of the old town of Hisar as well as a plan of the garden pavilion, known as Gujari Mahal and a plan and section of Lat ki Masjid. Other sites of the district of Hisar are not discussed. For the full report see: Hisar-i Firuza, Sultanate and Early Mughal Architecture in the District of Hisar, India.

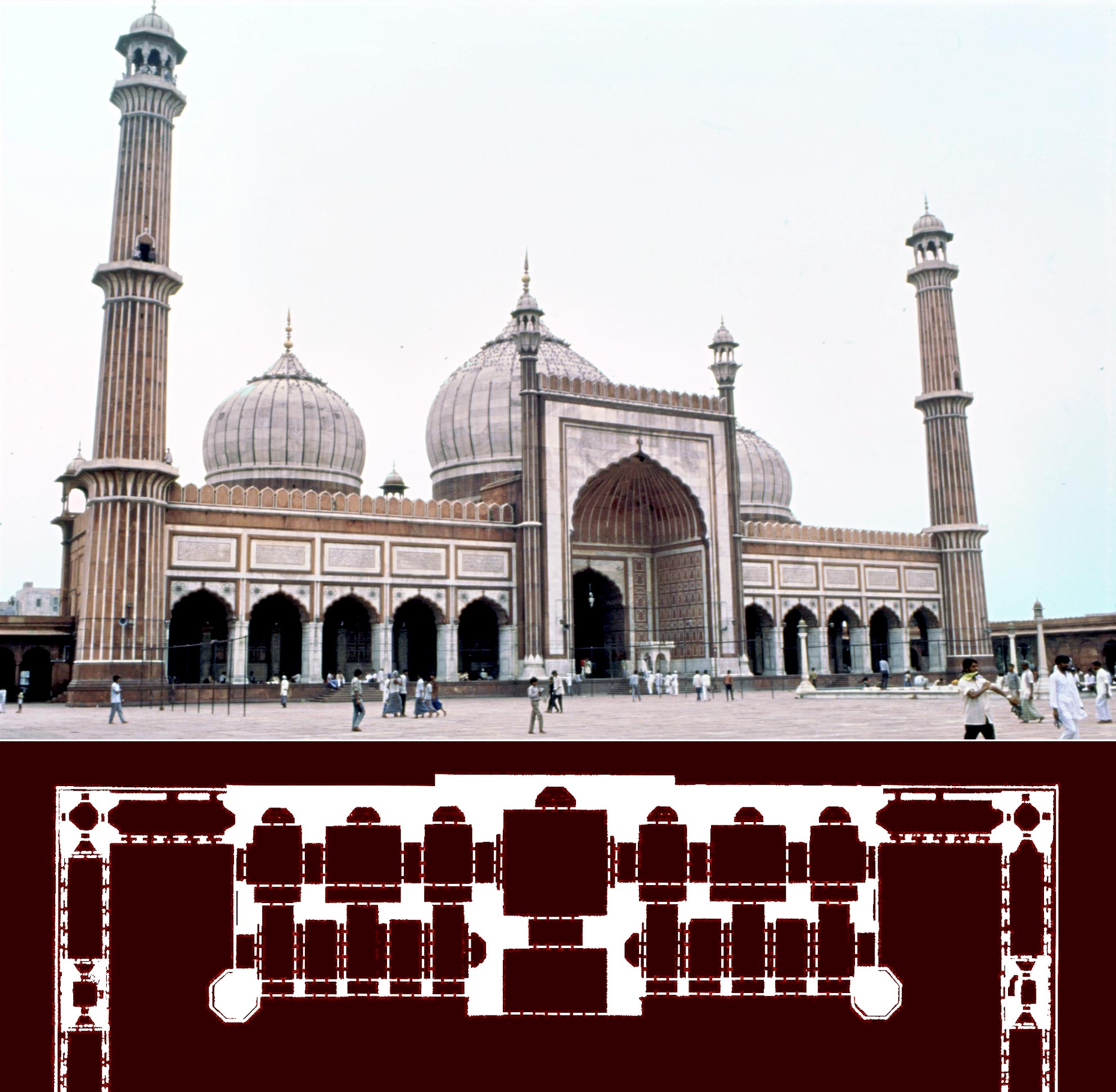

The royal mosque of Hisar built within the palace complex and known as Lat ki Masjid after the column (lat) set up by Firuz Shah in its courtyard. The lower register of the column is part of an ancient Ashokan pillar, the other part of which may be that in Fatehabad, again erected by Firuz Shah and inscribed with the early history of the Tughluq dynasty up to the beginning of his reign.

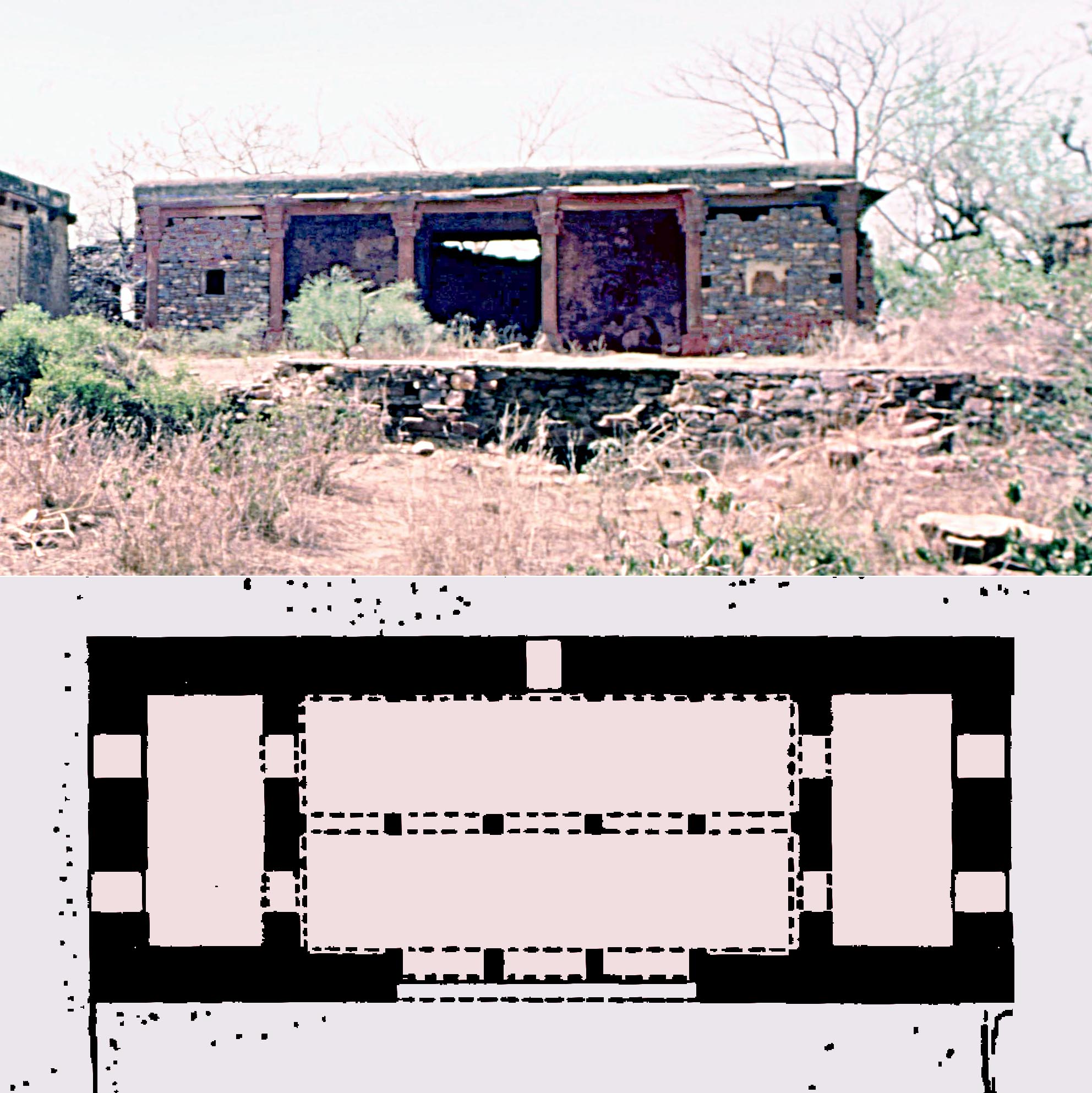

* “The Architecture of Baha al-din Tughrul in the region of Bayana, Rajasthan” M. and N. H. Shokoohy, Muqarnas, IV, 1987, pp. 114-32, figs 1-27 (9 architectural drawings, 20 photographs).

ISBN: 978-8-178240-10-7 ISSN: 0921-0326

“Malik Baha al-din Tughrul was of handsome disposition, very just and kind to the needy or strangers. He was a slave of long standing of the victorious sultan Mu‘izz al-din (Muhammad ibn Sam) who had brought him up and given him a good education. The fortress of Tahangar was in the territory of Bhayana ... When the sultan conquered it, he gave it to Baha al-din Tughrul who made that territory prosperous. Merchants and men of distinction from different parts of Hindustan and Khurasan joined him and he gave all of them houses and resources which were to be their own property, and for this reason they settled near him. As he and his army found the fort of Tahangar unsuitable he built the town of Sultankut in the territory of Bhayana, and here he made his abode... There was a speck of the dust of vexation between Malik Baha al-din Tughrul and Sultan Qutb al-din. Malik Baha al-din Tughrul was extremely benevolent and in the region of Bhayana numerous beneficial monuments of his have remained. He died and was received into the mercy of the Lord.”

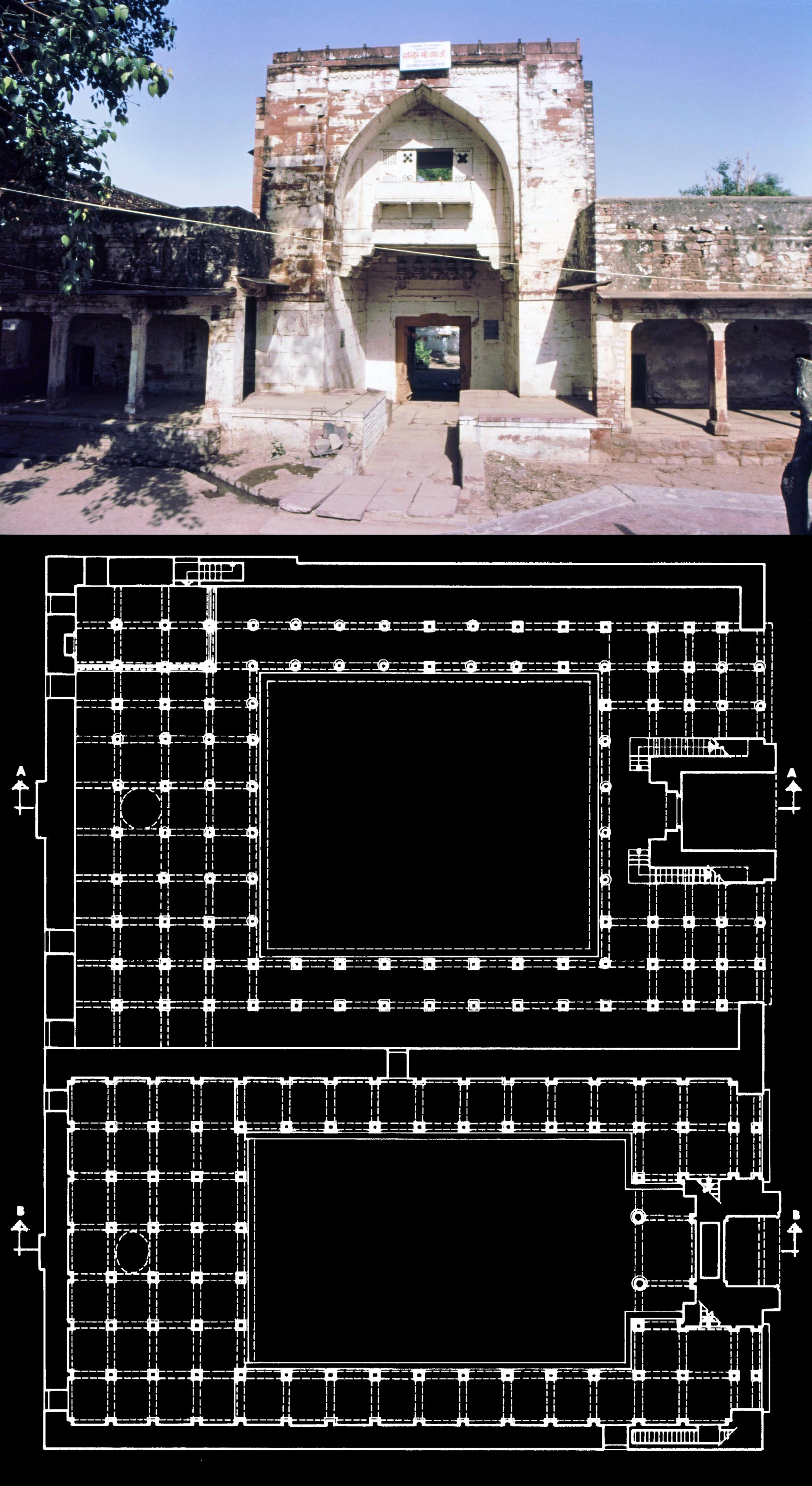

Minhaj-i Siraj, the historian of the early sultanate of Delhi, so describes the founder of Bayana. A rival of Qutb al-din Aibak (whose authority he did not accept) Baha al-din went as far as declaring himself sultan in an inscription in his mosque, the Chaurasi Khamba at Kaman, but died early during his governorship of Bayana so a conflict between him and Qutb al-din was averted. Two of Baha al-din’s mosques, the Chaurasi Khamba and in Bayana the Ukha Mandir Masjid (it has been converted to a temple) are amongst the earliest sultanate buildings in India.

Ukha Mandir Mosque, one of the oldest sultanate structures in

India dating from the end of the twelfth or very first years of

the thirteenth century. The arch of the portal is not a true arch,

but what is called a corbelled arch with stones laid horizontally.

In plan the structure with the smaller courtyard is an extension

of AD 1320-21 by Malik Kafur (Mubarak Shah Khalji’s governor)

and known as Ukha Masjid.

Ukha Masjid, praised by the fourteenth century Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta.

In later dates an extension, now known as Ukha Masjid was built at one side of the Ukha Mandir mosque at the time of Mubarak Shah Khalji in AH 720 (AD 1320-21). The mosque and its extension, when still very new, was visited by Ibn Battuta who notes: “Bayana is a great city and has fine buildings and attractive bazaars, and its Jami‘ is one of the finest mosques, with walls and ceilings all of stone”.

The mosques of Baha al-din, built out of temple spoil, represent the distinctive features of the earliest sultanate mosques, including multiple prayer niches (mihrabs) and a dedicated royal chamber known as muluk khana or shah nishin, at the north side of the prayer hall. These features became characteristics of the architecture of the sultanate mosques, a trend that continued for several centuries.

The mosques of Baha al-din, built out of temple spoil, represent the distinctive features of the earliest sultanate mosques, including multiple prayer niches (mihrabs) and a dedicated royal chamber known as muluk khana or shah nishin, at the north side of the prayer hall. These features became characteristics of the architecture of the sultanate mosques, a trend that continued for several centuries.

As well as the mosques, the prayer wall (‘idgah) of Bayana, likely to date from the time of Baha al-din Tughrul, making it the oldest specimen of its kind in India, is also discussed.

The ʽidgah or namazgah of Bayana has, instead of

a simple mihrab (prayer niche), a small chamber in

the centre. This feature, together with the corbelled

instead of true arches, indicates its early date.

“Muslim architecture in Gujarat prior to the Islamic conquest”, M. Shokoohy, Marg, XXXIX, iv, 1988, pp. 75-78, figs 1-9 (1 architectural drawing, 8 photographs).

“Muslim architecture in Gujarat prior to the Islamic conquest”, M. Shokoohy, Marg, XXXIX, iv, 1988, pp. 75-78, figs 1-9 (1 architectural drawing, 8 photographs).

ISSN: 0972-1444

Gujarat was the only region in India to have an established tradition of Muslim architecture before the Islamic conquest. To introduce the material in the book Bhadresvar, the oldest Islamic monuments in India, the shrine of Ibrahim and the two mosques: the Solahkhambi and the Chhoti Masjid in Bhadresvar (Bhadreshwar) as well as the mosque of Abu’l-Qasim b. ʽAli al-Idhaji (or al-Iraji) in Junagadh are briefly considered and the stylistic development of the architecture of the Muslim trading communities on the Gujarat coasts during the twelfth and thirteenth century is discussed.

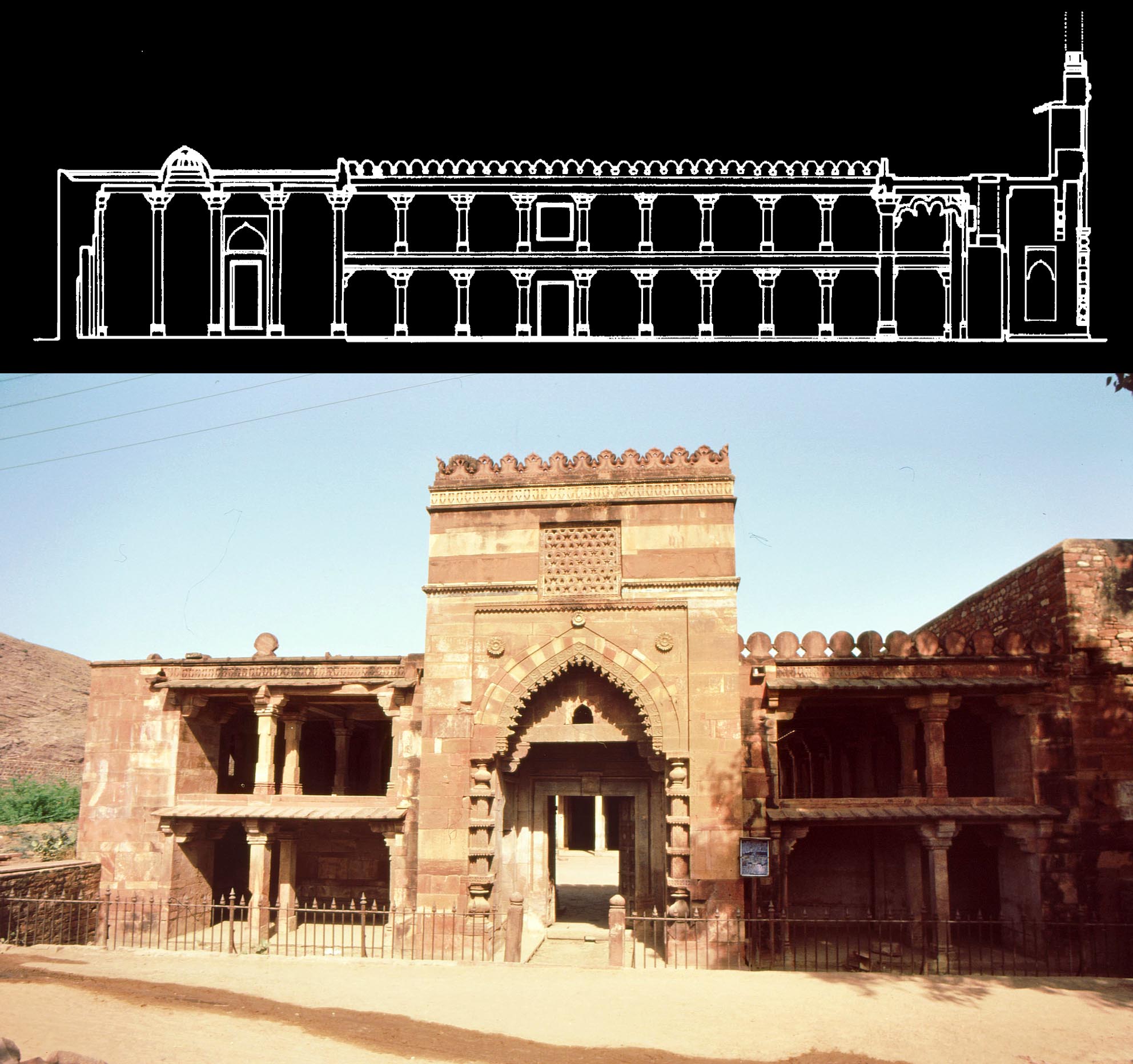

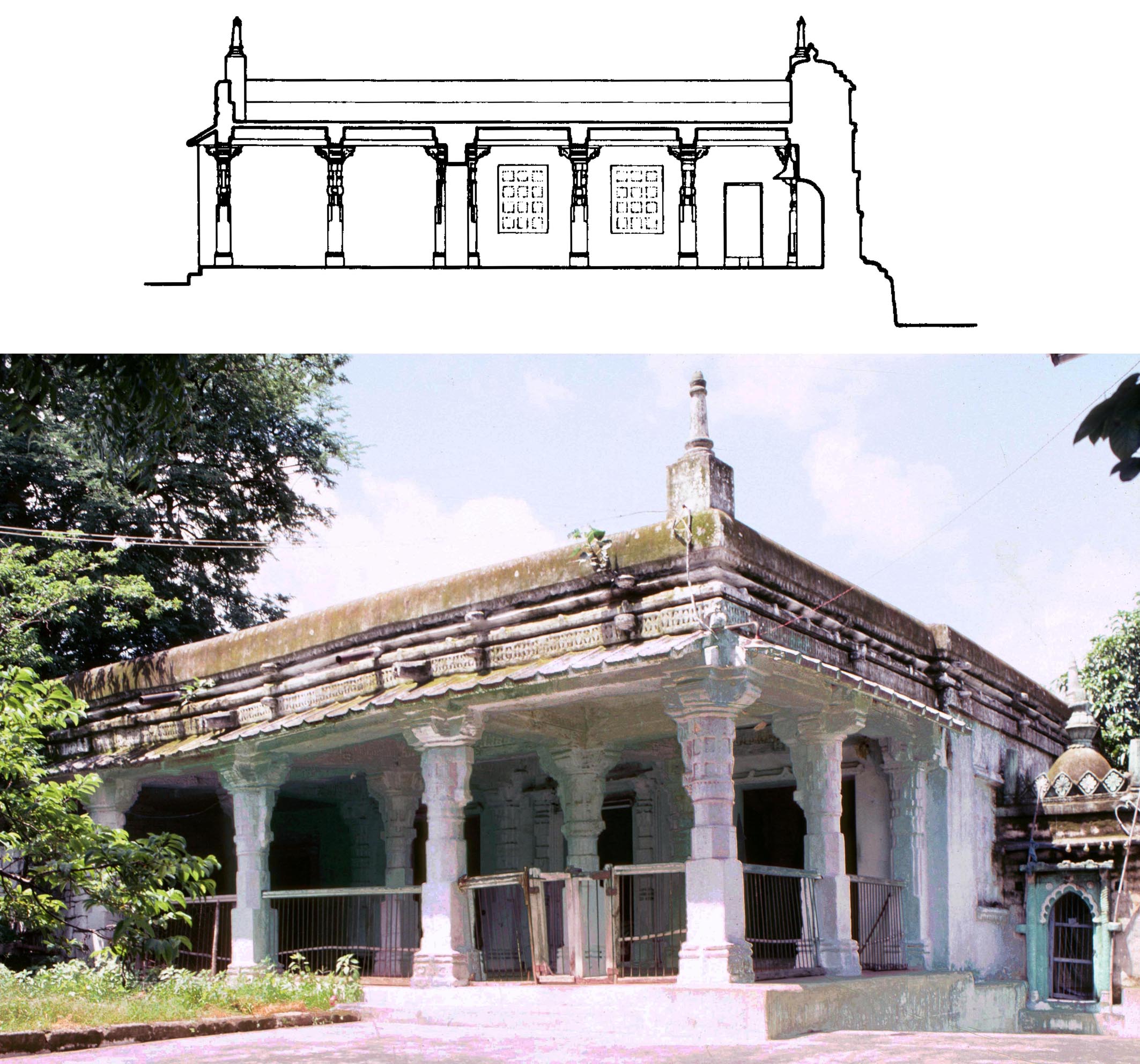

The mosque at Junagadh built in AD 1286-7 by Abu’l Qasim b. ʽAli, the head of the merchants and shipmasters of the town. The grand portico in front of the prayer hall is a hallmark of the buildings of the Muslim maritime traders on the Indian littoral.

* “Architecture of the Sultanate of Ma'bar in Madura and other Muslim monuments in South India”, M. Shokoohy, JRAS, 1991, pp. 31-92, figs 1-18, pls 1-16 (32 monochrome photographs).

The obscure history of the short-lived fourteenth-century Sultanate of Ma`bar and the monuments related to it in present Tamil Nadu, presented first in a lecture to the Royal Asiatic Society in 1990, was the first report (extended for this paper) of the wide-ranging project of surveying the then almost unknown Muslim architecture of the South India littoral, culminating in the publication of Muslim Architecture of South India.

The obscure history of the short-lived fourteenth-century Sultanate of Ma`bar and the monuments related to it in present Tamil Nadu, presented first in a lecture to the Royal Asiatic Society in 1990, was the first report (extended for this paper) of the wide-ranging project of surveying the then almost unknown Muslim architecture of the South India littoral, culminating in the publication of Muslim Architecture of South India.

The tomb of Sultan ʽAla al-din Udauji in Madura where Sultan Shams al-din `Adil Shah is also buried was brought to the attention of scholars, and on the same site the tombs of Sayyid Husain Quddus’ullah (belived to be a vezier of `Ala al-din) and Shaikh Muhammad `Abd’ullah Bara Mastan Sada Pir were also discussed. These edifices are just outside old Madura, where the Muslim graveyard must have been. In the old town, and not far from the grand Sri Minakshi temple, the historic mosque of Qadi Taj al-din was also examined. Far away from Madura in Tiruparangundram, the site of the final episode of the sultanate of Ma`bar, the tomb of Sikanar Shah (the last sultan, killed in a battle with the Vijayanagar forces) was also studied.

The tomb of Sultan ʽAla al-din Udauji in Madura where Sultan Shams al-din `Adil Shah is also buried was brought to the attention of scholars, and on the same site the tombs of Sayyid Husain Quddus’ullah (belived to be a vezier of `Ala al-din) and Shaikh Muhammad `Abd’ullah Bara Mastan Sada Pir were also discussed. These edifices are just outside old Madura, where the Muslim graveyard must have been. In the old town, and not far from the grand Sri Minakshi temple, the historic mosque of Qadi Taj al-din was also examined. Far away from Madura in Tiruparangundram, the site of the final episode of the sultanate of Ma`bar, the tomb of Sikanar Shah (the last sultan, killed in a battle with the Vijayanagar forces) was also studied.

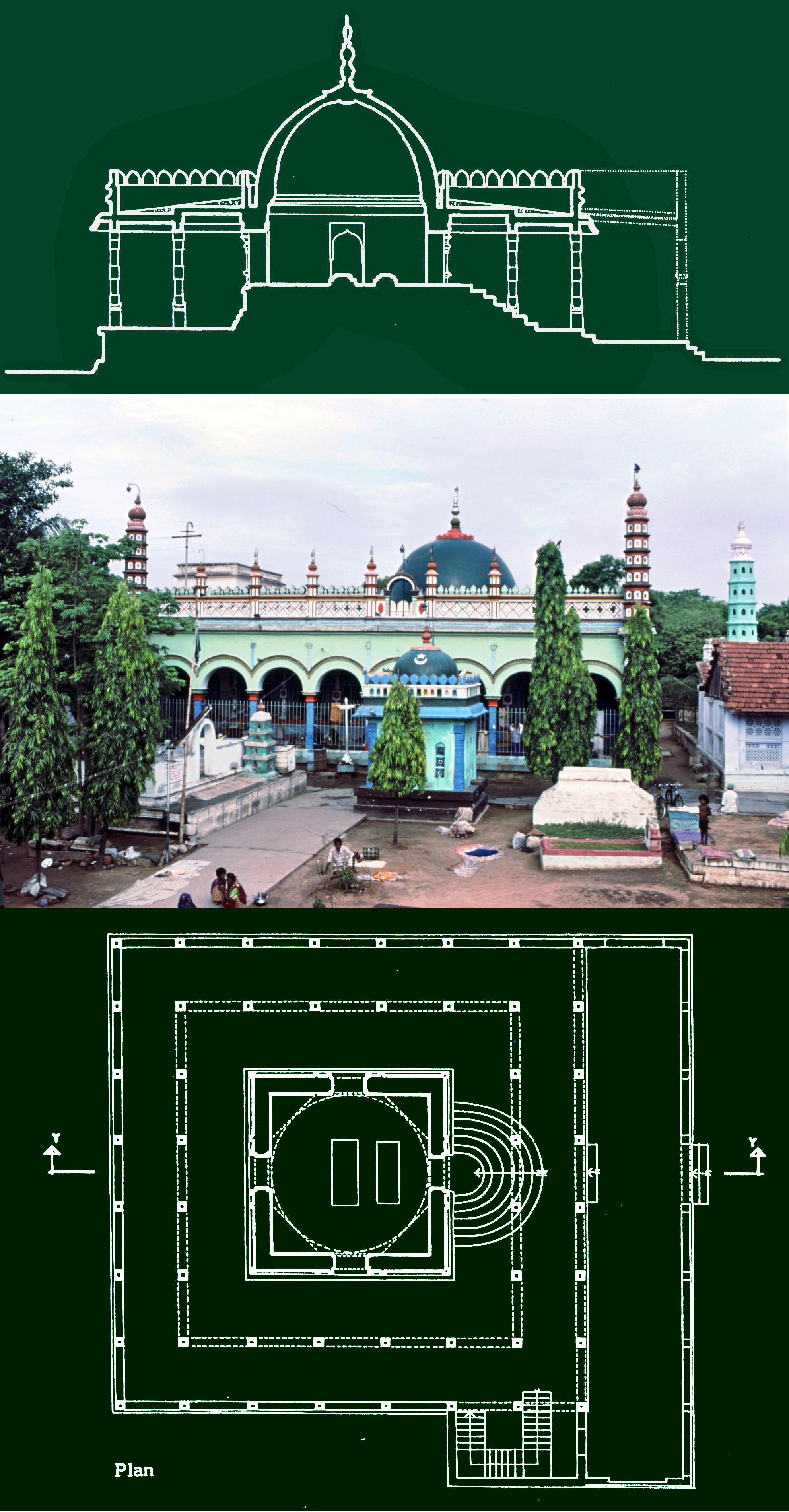

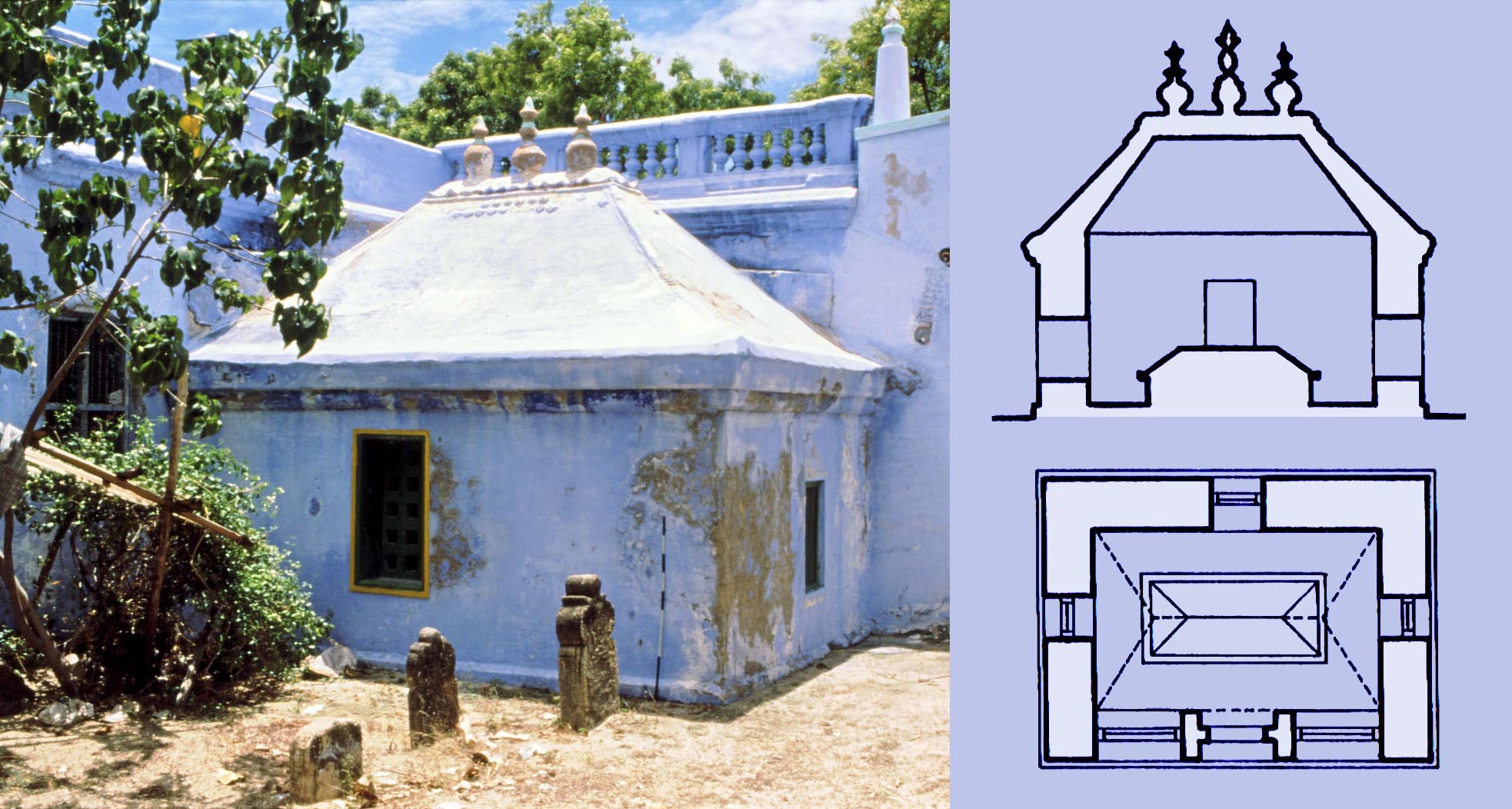

The square domed chamber surrounded by a colonnade

two bays deep houses the tombs of ʽAla al-din Udauji

(c. AD 1338-9) and Shams al-din ʽAdil Shah (c. 1356-72).

The form is alien in South India, but resembles the tomb

chambers of Gujarat. In the garden and in front of the

tomb of ʽAla al-din and Shams al-din stands the small

chatri tomb of Sayyid Husain Quddus’ullah.

The mosque next to the tomb of ʽAla al-din and Shams al-din, with a colonnaded portico almost as large as the prayer hall, characteristic of the mosques of the maritime merchants. An inscription of Shams al-din ʽAdil Shah in the compound confirms the existence of such traders in his territory.

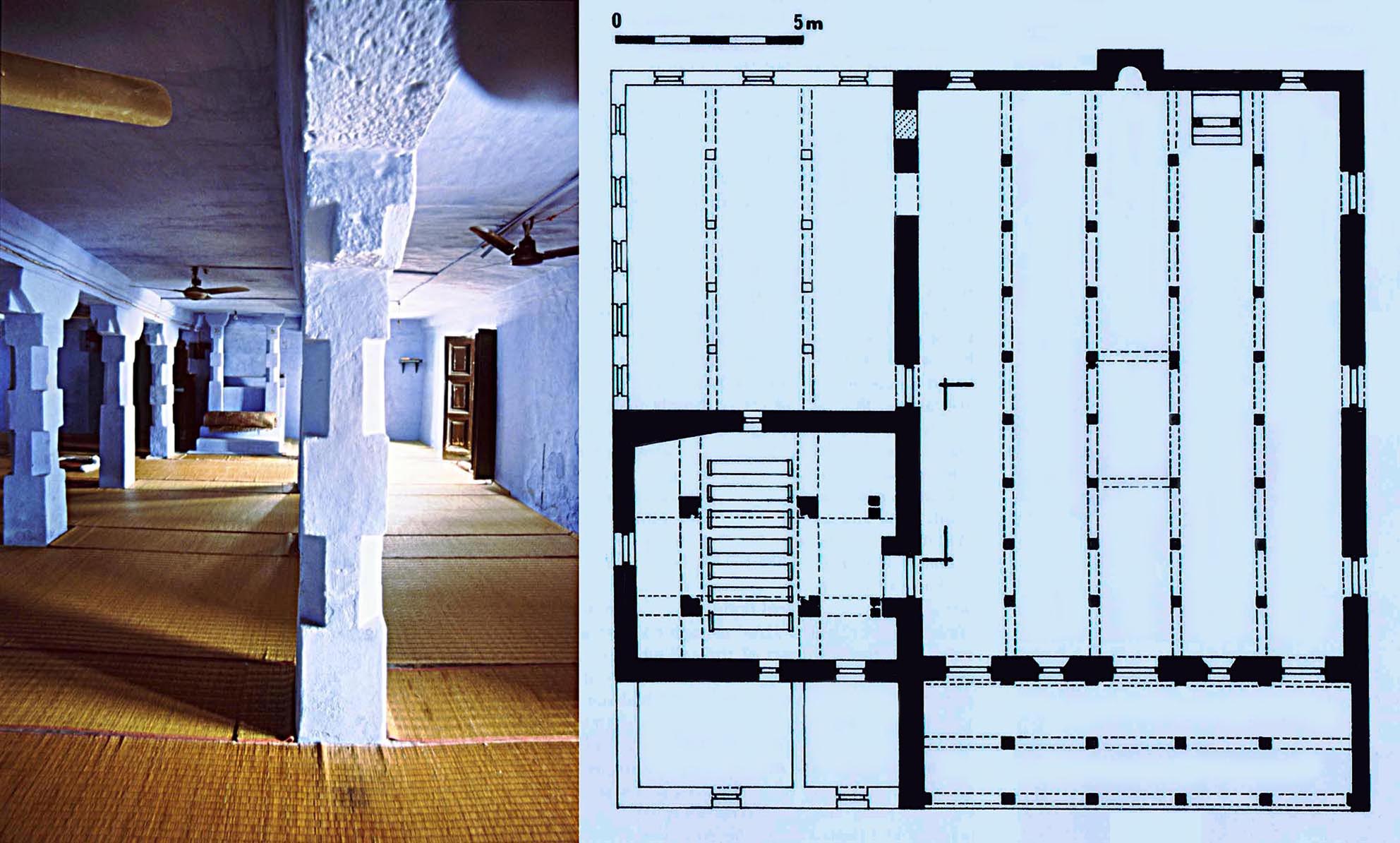

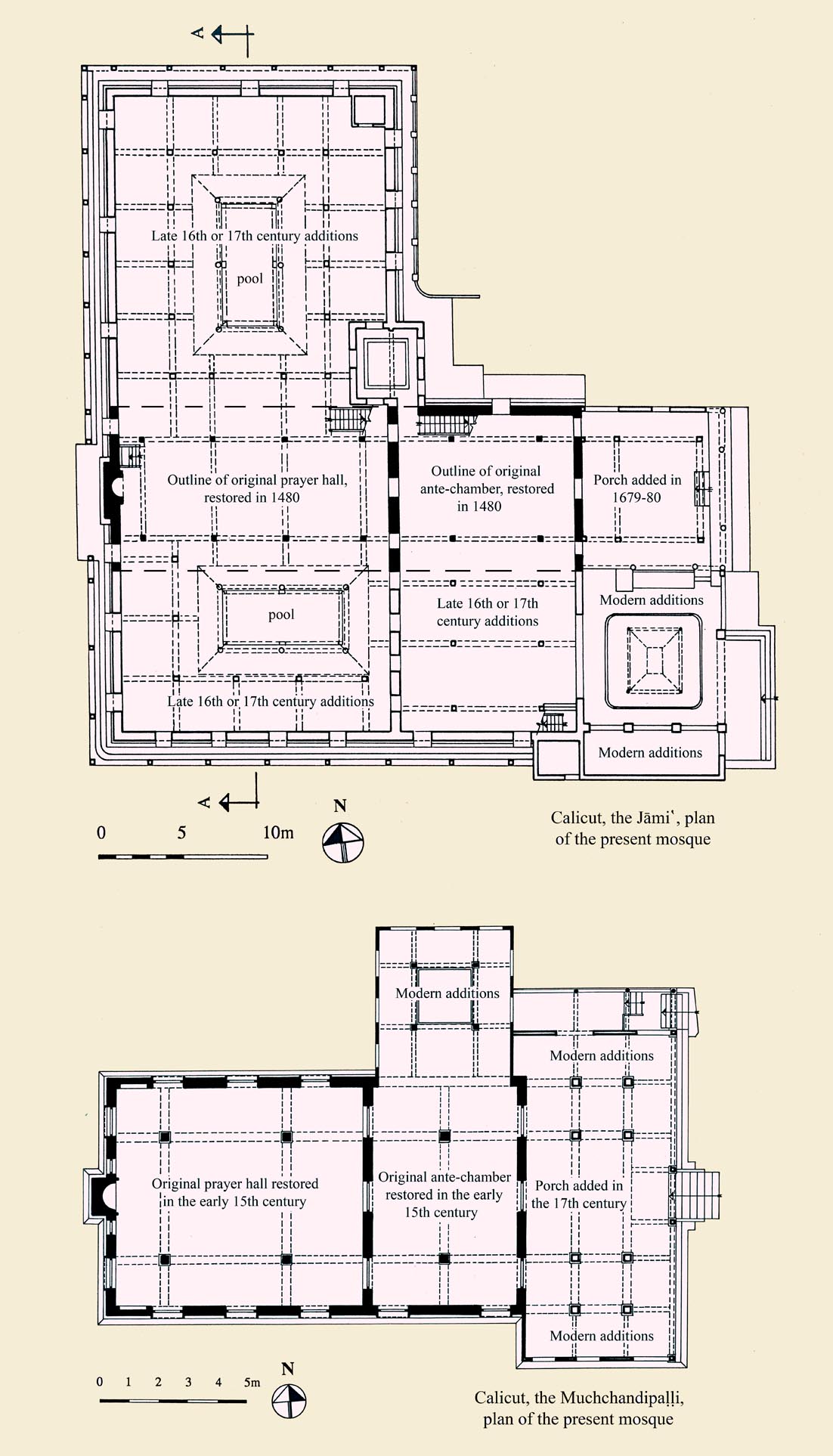

Brief notes of the monuments of Calicut with some sketch drawings are also given (superseded by detailed survey drawings made in later fieldwork). For a full account of the sites discussed see the book: Muslim Architecture of South India.

“History and Architecture of Kirtipur, Nepal”, M. and N. H. Shokoohy, South Asia Library Group Newsletter, XXXIX, 1992, pp. 25-9, 2 figs.

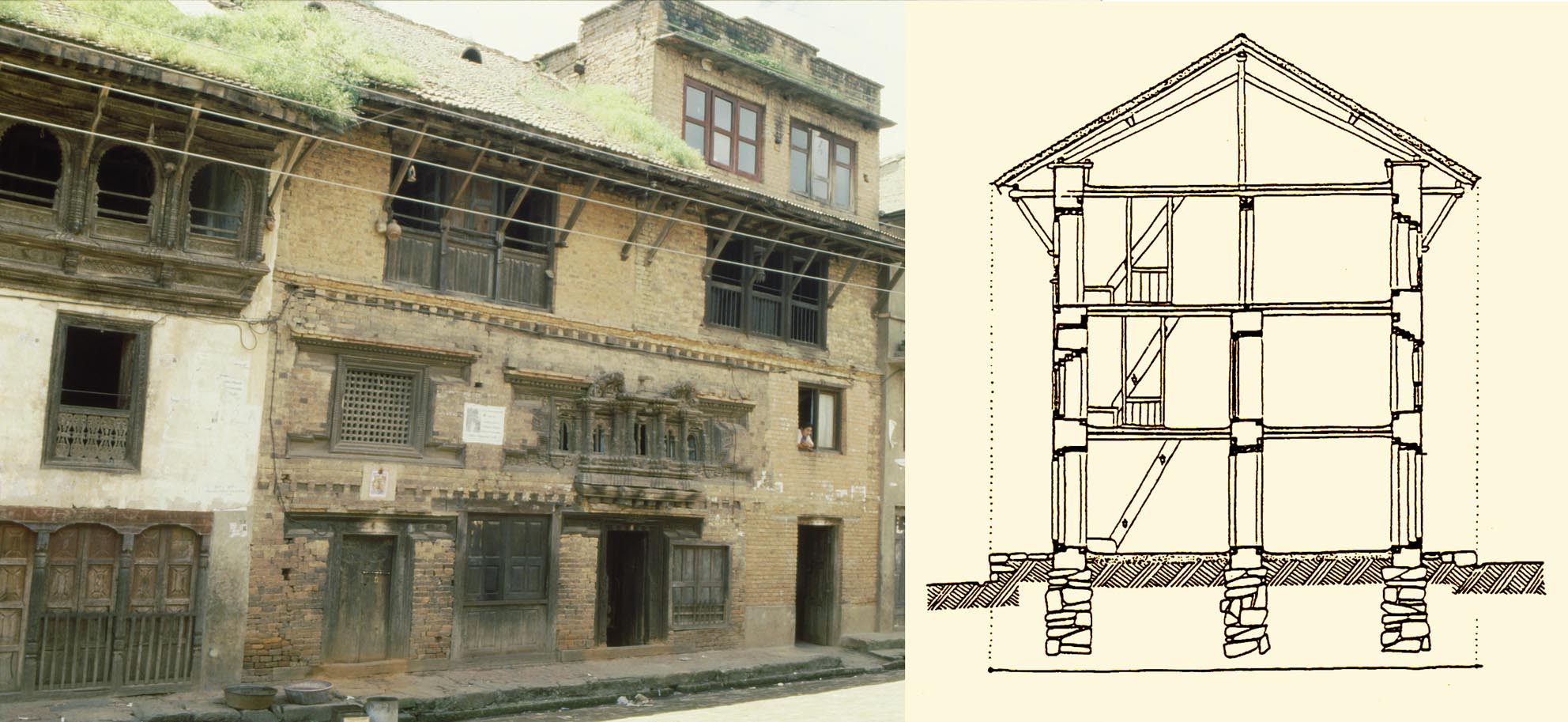

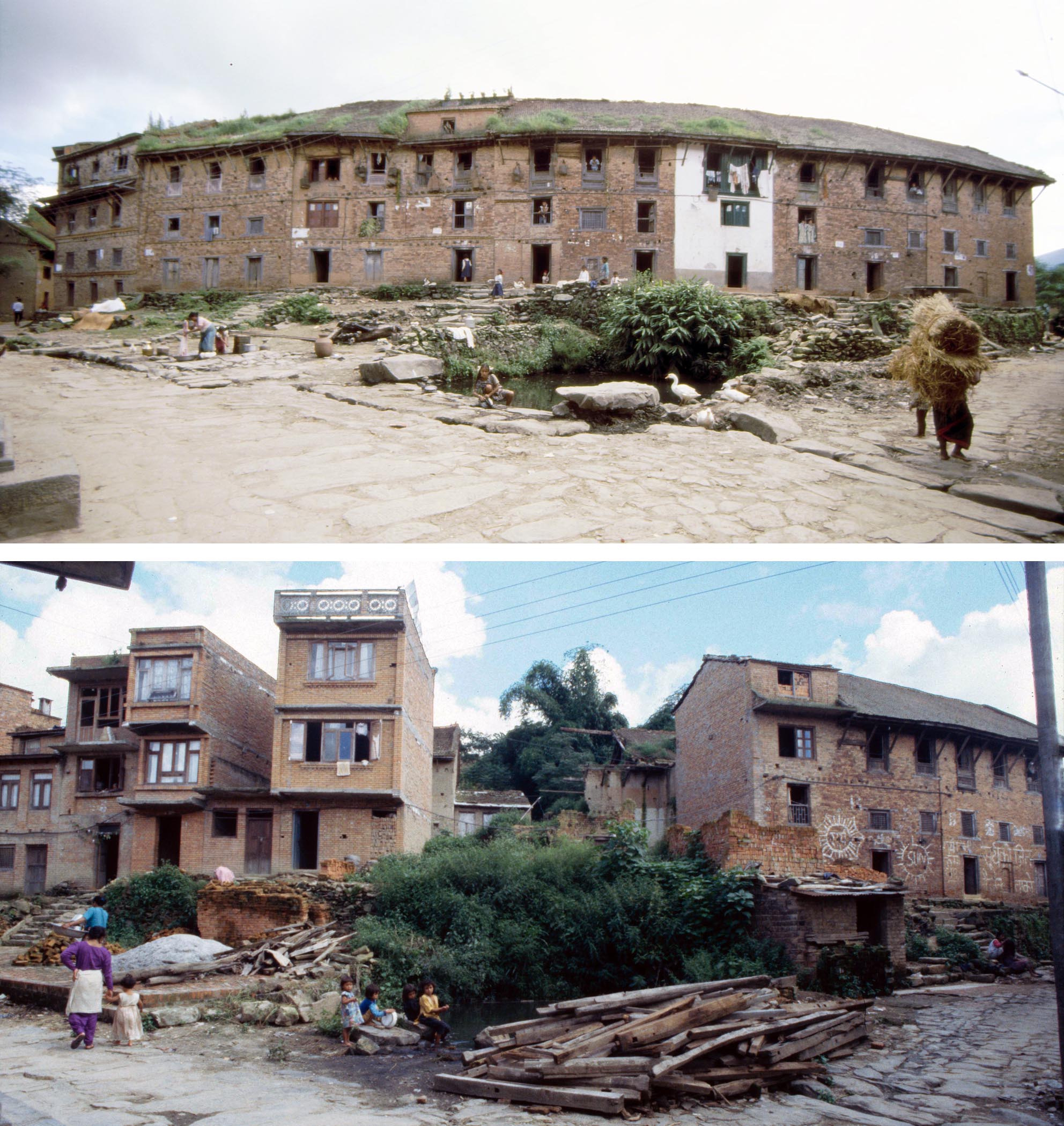

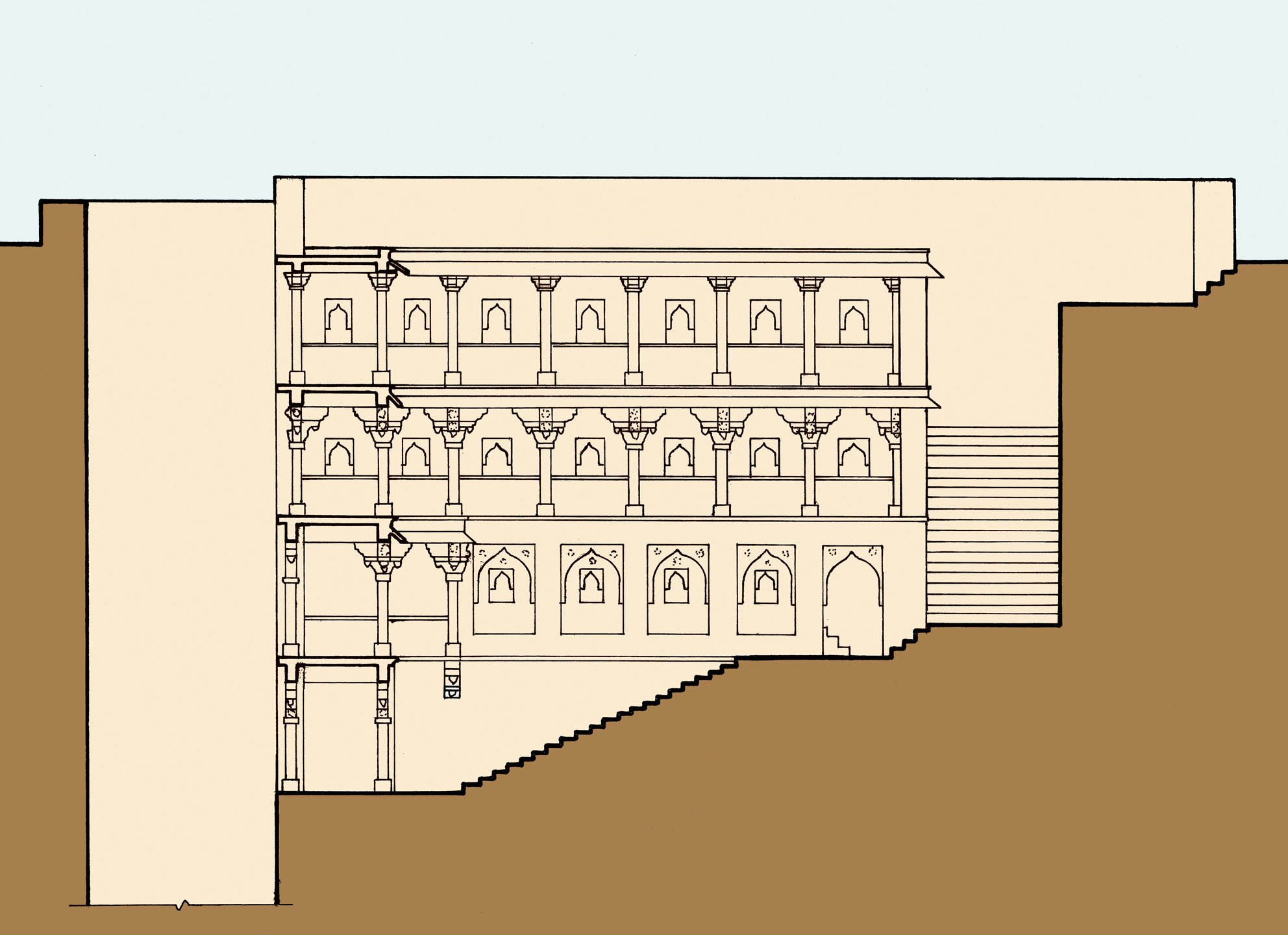

By the 1990s the art, architecture and social life of Nepal’s major urban centres and some distant locations had become well known through books, films and its popularity as a travel destination. Kirtipur, however, in spite of its historic importance as a former Newar capital and its proximity to Kathmandu had remained out of the picture. In an illustrated talk in 1992 at the Royal Asiatic Society the Shokoohys brought the town to the attention of the members of the South Asia Library Group. Mehrdad Shokoohy discussed the history, caste system and social structure of the town reflected in the morphology of the town plan, and Natalie Shokoohy introduced the architectural characteristics of Kirtipur. The paper includes an account of the hierarchical organisation of houses as the sacred territory of the family – with the ground floor as a transitional zone which outsiders can enter, progressing to the first floor, representing the world of people, where the family lives and people of acceptable caste may also enter, to the second floor, symbolising the celestial regions and housing the more private family accommodation, and finally the attic, the most sacred part of the house where food is prepared and only the close family gather.

Religion plays a dominant role in the urban fabric with Buddhists and Hindus living in harmony, but in distinct quarters. Although this tradition is gradually eroding, the Hindu temples such as the Bagh Bhairav and Uma Mheshvara are in the historic Hindu area while the Budhhist shrines, monasteries and the impressive Chilancho Stupa are surrounded by clusters of dwellings inhabited by Buddhists. The paper was an early report of the project of studying multiple aspects of the town, its people, urban form, religious and domestic architecture, resulting on the publication of Kirtipur: an Urban Community in Nepal two years later and the Street Shrines of Kirtipur in 2014.

Religion plays a dominant role in the urban fabric with Buddhists and Hindus living in harmony, but in distinct quarters. Although this tradition is gradually eroding, the Hindu temples such as the Bagh Bhairav and Uma Mheshvara are in the historic Hindu area while the Budhhist shrines, monasteries and the impressive Chilancho Stupa are surrounded by clusters of dwellings inhabited by Buddhists. The paper was an early report of the project of studying multiple aspects of the town, its people, urban form, religious and domestic architecture, resulting on the publication of Kirtipur: an Urban Community in Nepal two years later and the Street Shrines of Kirtipur in 2014.

A traditional house in Layaku, opposite the site of the old palace, and a section through a typical Newar house, with the platform under the eaves and the ground floor being an interface between the householder and customers or passers-by, while the upper floors become progressively more private with the kitchen in the attic the most secluded area.

* “Architecture of the Muslim Port of Qa'il on the Coromandel Coast, South India, Part One, History and the 14th-15th Century Monuments”, M. Shokoohy, SAS, vol. IX, 1993, pp. 137-166, figs. 1-15 (2 maps and 27 architectural drawings), pls 1-16

The first interim report on the historic port of Qaʽil (now Kayalpatnam) in Tamil Nadu embarked on an account of its extensive architectural heritage. The work was part of a wider project started in 1988 and culminating in 2003 with the publication of Muslim Architecture of South India, with the aim of recording the architecture of the Muslim maritime settlers. Four seasons of fieldwork were carried out in 1988, 1990, 1994 and 1996.

The first interim report on the historic port of Qaʽil (now Kayalpatnam) in Tamil Nadu embarked on an account of its extensive architectural heritage. The work was part of a wider project started in 1988 and culminating in 2003 with the publication of Muslim Architecture of South India, with the aim of recording the architecture of the Muslim maritime settlers. Four seasons of fieldwork were carried out in 1988, 1990, 1994 and 1996.

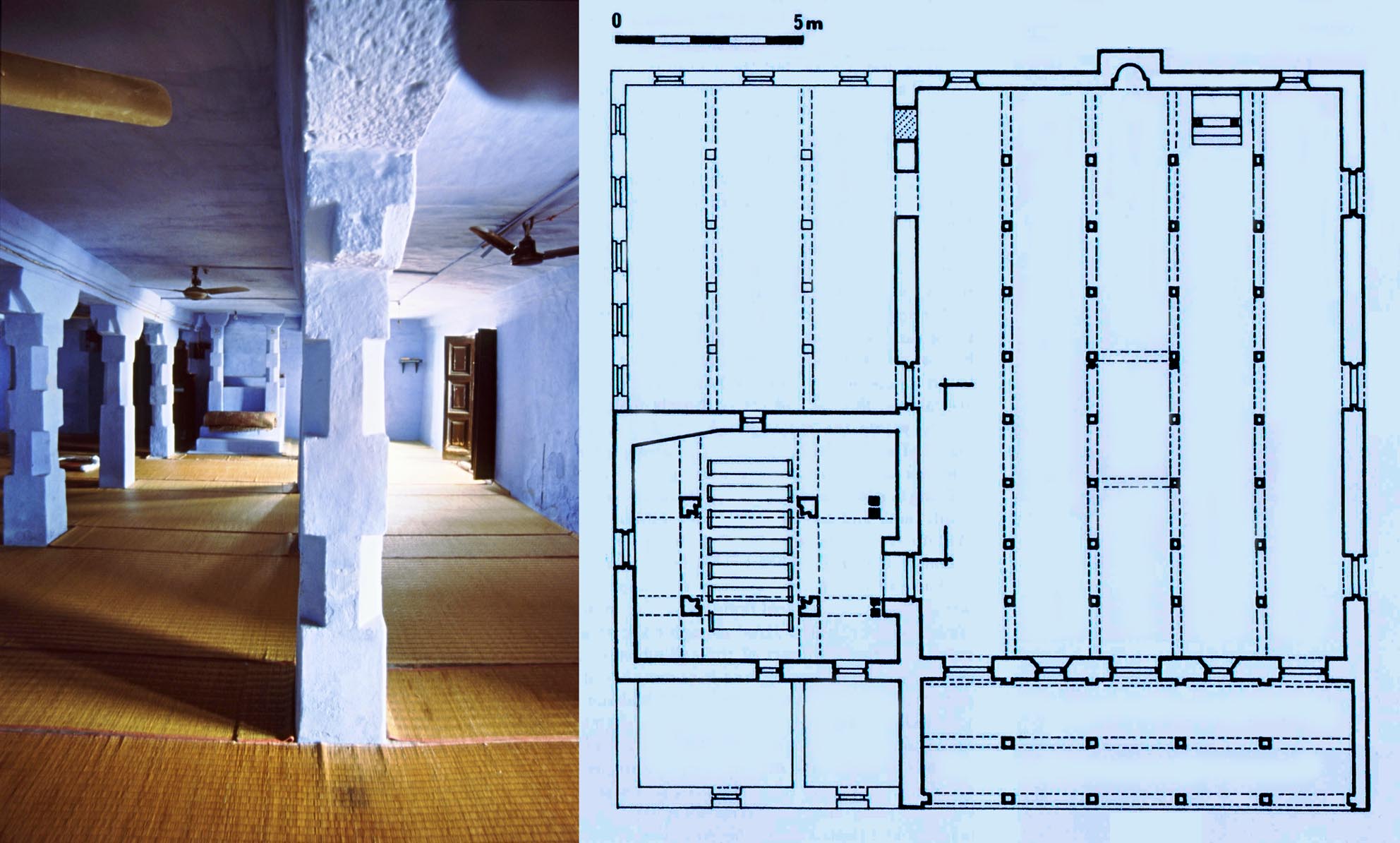

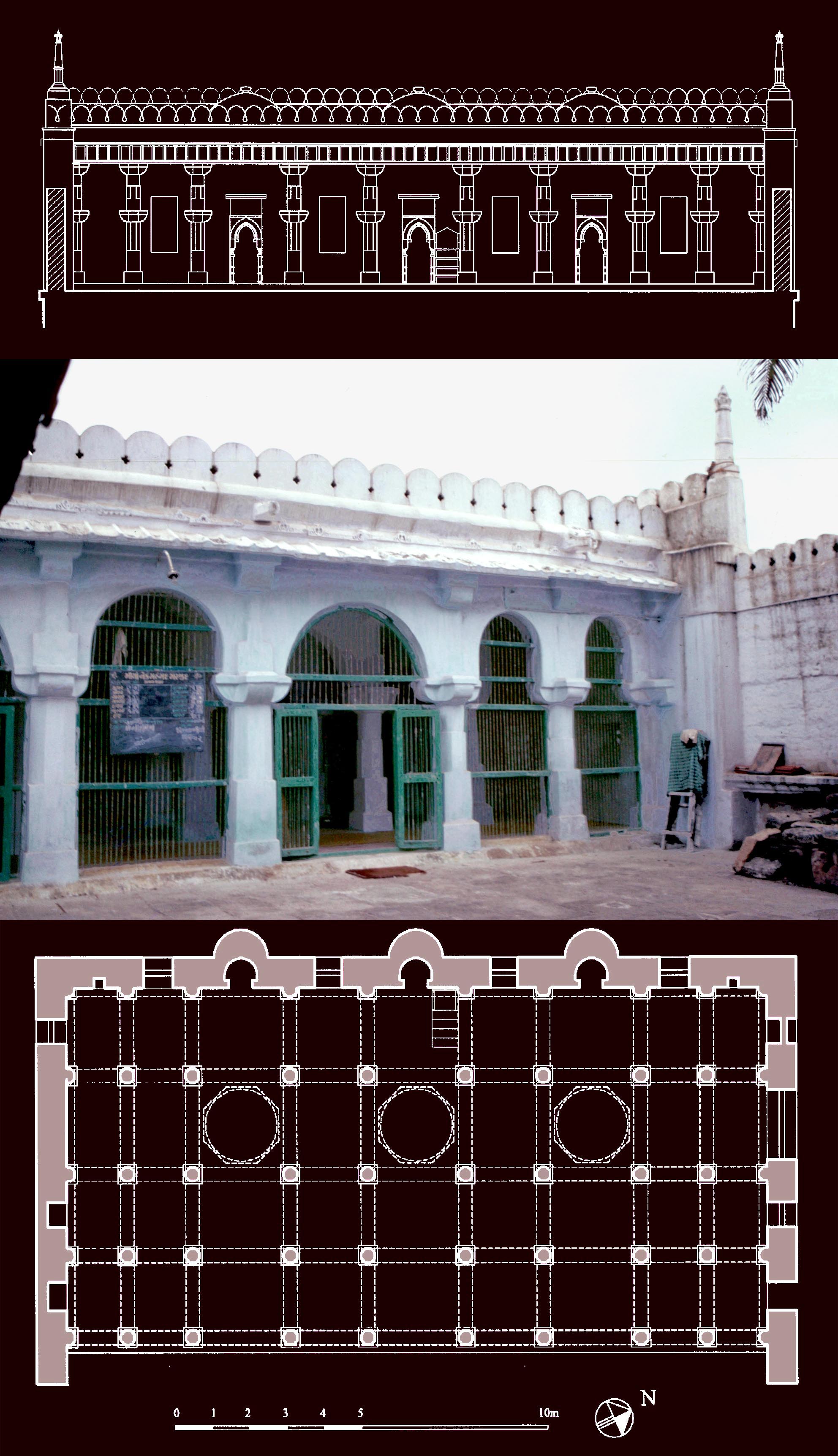

The Jamiʽ al-saghir, the smaller congregational mosque

of Kayalpatnam, which although not dated must belong

to at least the fourteenth century on account of the dated

tombstones in the chamber attached to the prayer hall.

Ahmad Nainar, a small but pleasant building featuring the characteristics of a Muslim trading community mosque including a fairly large portico in front of the prayer hall.

The history of the port, visited among others by Marco Polo, is given; he noted: "Cail is a great and noble city, and belongs to Ashar, the eldest of the five brother kings. It is at this city that all the ships touch that come from the west, as from Hormos and from Kis and from Aden and all Arabia, laden with horses and with other things for sale, and this brings a great concourse of people from the country round about, and so there is great business done in this city of Cail".

Decorative details on the parapet of the roof of

the Ahmad Nainar Mosque relate to the features

known as vajramastaka in early Buddhist and

Hindu temples. Similar motifs also appear around

the roof of the Greater Jamiʽ, which bears a date

of AH 737 (AD 1336-7).

A map of the region as well as a town plan of Kayalpatnam shows the location of major monuments. The historic remains are discussed beginning with the two Jami` mosques, the greater bearing an inscription recording its construction in AH 737/AD 1336-7, and the smaller, possibly even earlier. Other earlier buildings described include the mosques of Ahmad Nainar, the Qadiriya, and Ahmad Makhdum Wali (d. 539/1144-5), all of which are entirely roofed, a characteristic of South Indian mosques -- which unlike those of North India, do not have courtyards in front of a prayer hall. Numerous drawings of plans, sections and details of the special features set out the salient characteristics.

* “Architecture of the Muslim Port of Qa'il on the Coromandel Coast, South India, Part Two, the 16th-19th Century Monuments” M. Shokoohy, SAS, vol. X, 1994, pp. 162-178, figs 1-8 (1 map, 20 architectural drawings), pls. 1-14.

* “Architecture of the Muslim Port of Qa'il on the Coromandel Coast, South India, Part Two, the 16th-19th Century Monuments” M. Shokoohy, SAS, vol. X, 1994, pp. 162-178, figs 1-8 (1 map, 20 architectural drawings), pls. 1-14.

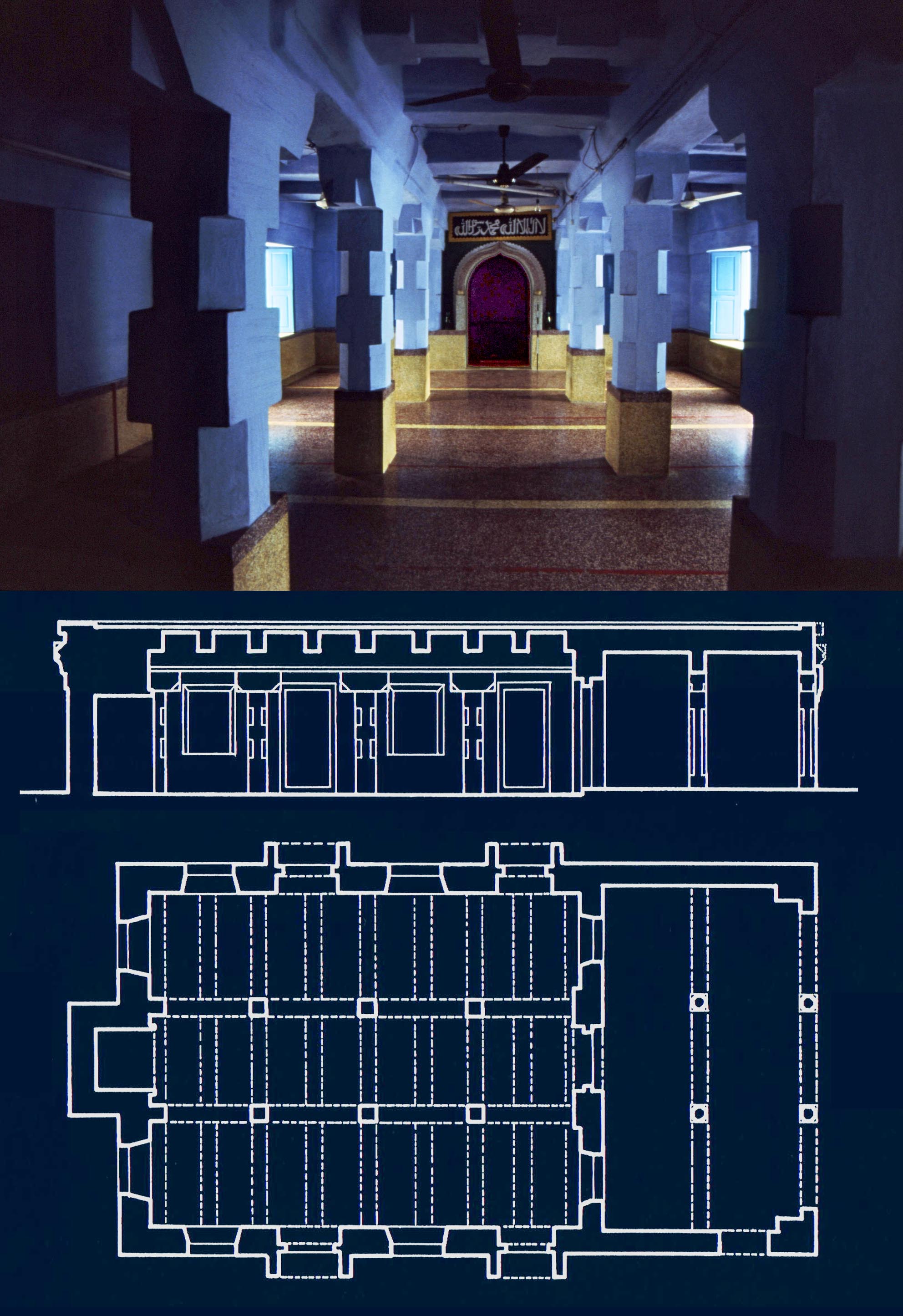

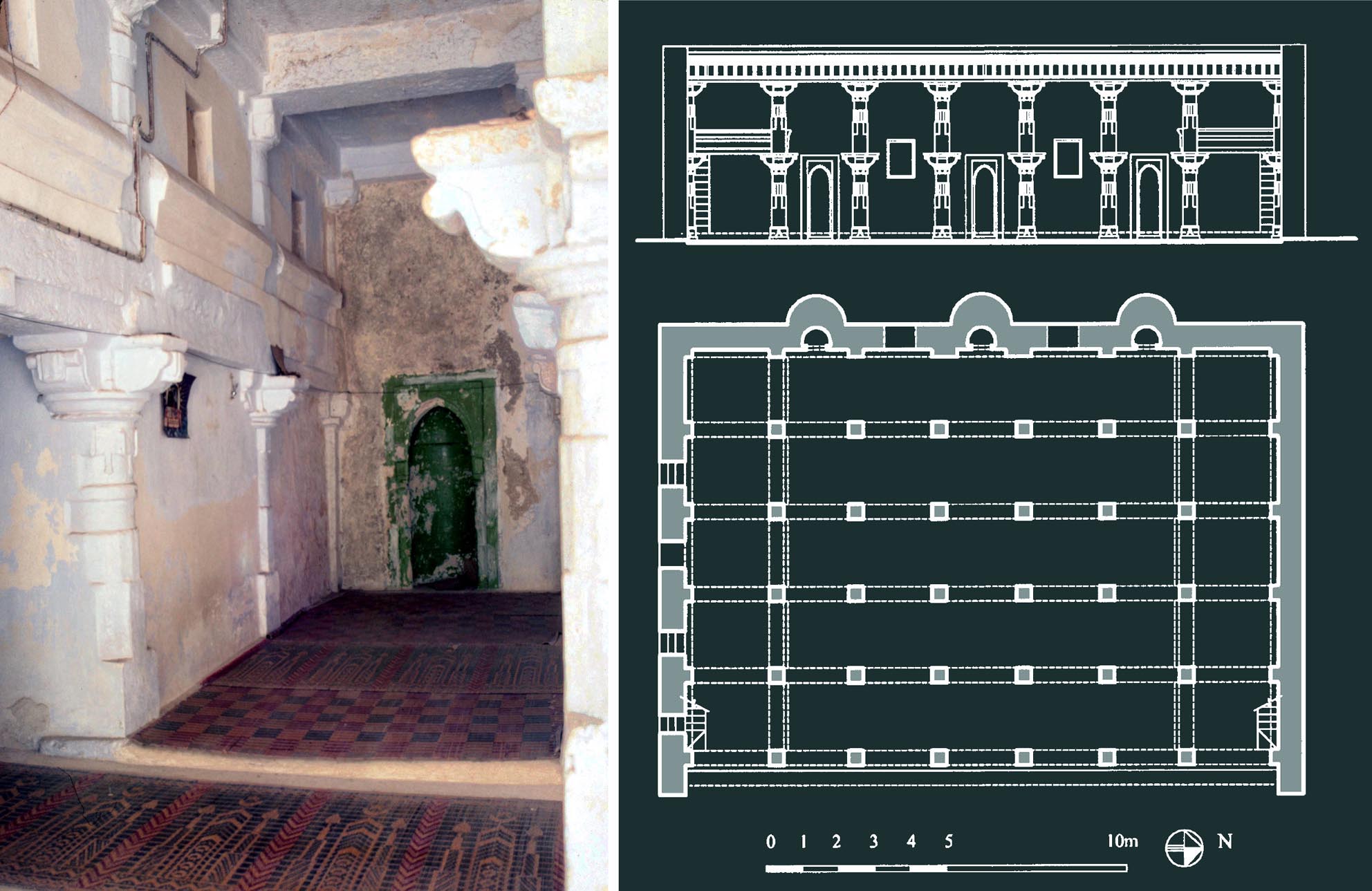

Rettaikulampalli, one of the finest small mosques of Kayalpatnam, the plan of which presents some innovations, including the wide central aisle, but the traditional portico in front of the prayer hall is maintained.

The second interim report on Kayalpatnam – the historic port of Qa`il – is concerned with the later monuments of the town, discussing the development in the design of mosque plans as well as the more elaborate carvings of the architectural elements. The mosques of Rettaikulampalli, Marakkayarpalli, Kadayapalli and Mahalara are described, supported by survey drawings as well as the shrines, including Koshmurai Appa and the tombs of Shaikh Sulaiman, and Shaikh Sam Shahab al-Din Wali'ullah.

The interior of Rettaikulampalli displays finely decorated monolithic

The interior of Rettaikulampalli displays finely decorated monolithic

columns, inspired by the late sixteenth to seventeenth century Hindu

architecture of Tamil Nadu. Similar columns appear in the renovated

centre of the prayer hall of the Greater Jamiʽ.

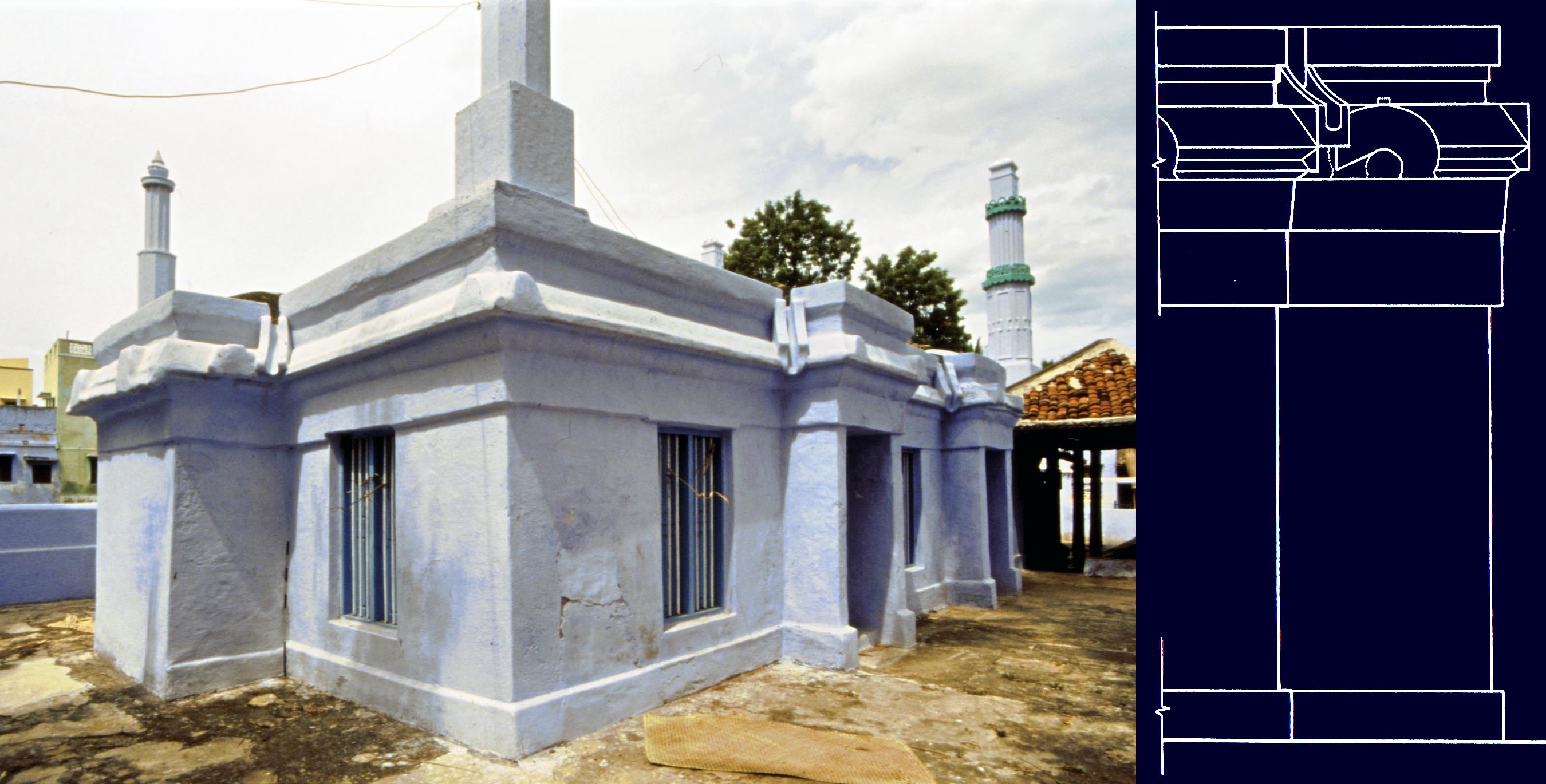

These tombs, while built entirely with stone, have hipped roofs, complete with three finials, imitating the form of timber roofs in Malabar (the west coast of India), indicating that timber structures with hipped roofs must have been commonplace in the past. Existing examples can still be found in the Kattupalli and in some of the nineteenth and early twentieth century extensions to the earlier mosques. For the final report of the whole area see Muslim Architecture of South India.

The tomb of Shaikh Sulaiman (AD 1591-1669) built of stone, but in the style of a wooden structure with a hipped roof and three finials, showing that wooden buildings in the South and South-East Asian style would have been more common in the region then they are now.

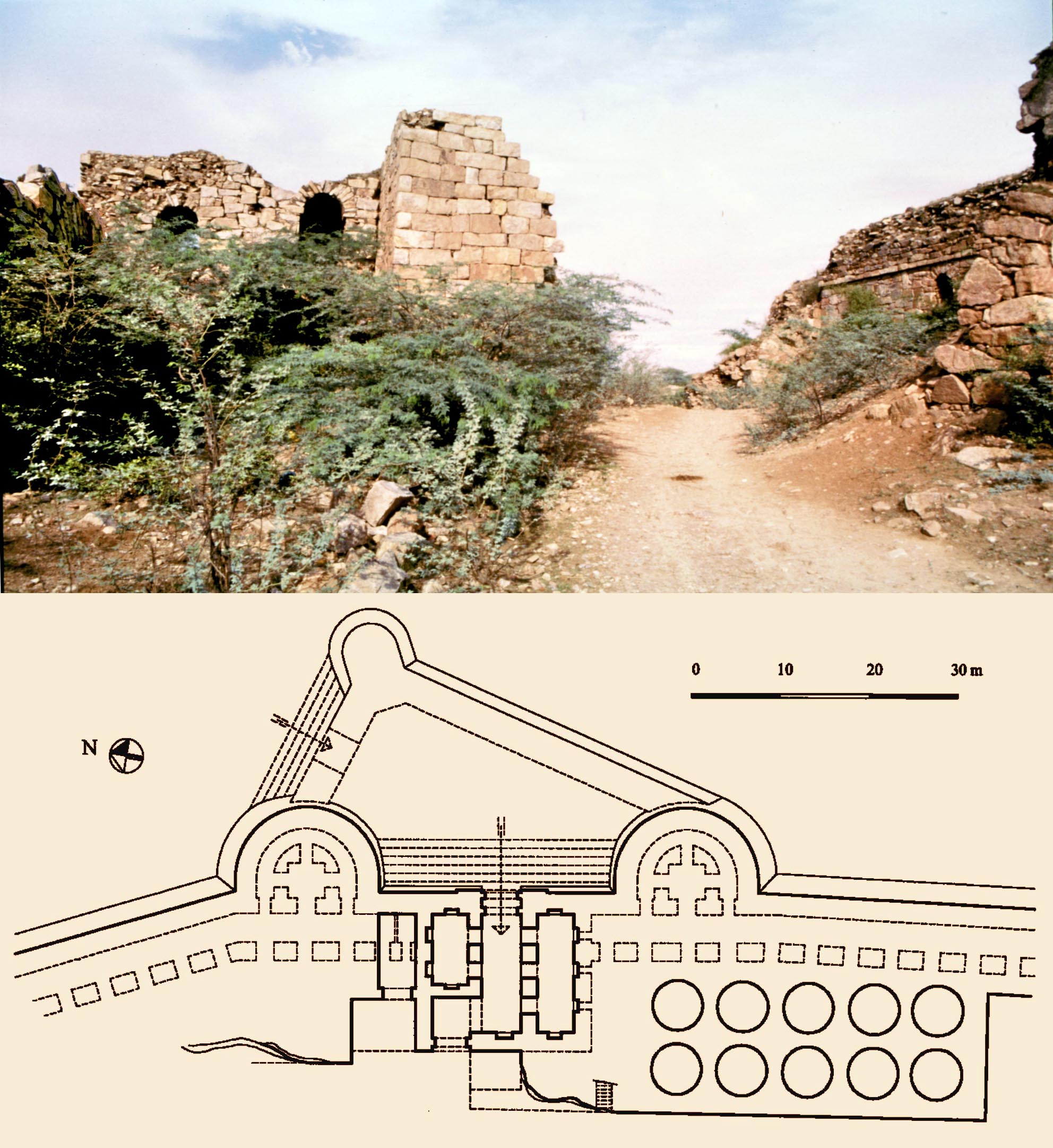

* “Tughluqabad, the earliest surviving town of the Delhi Sultanate” M. and N. H. Shokoohy, BSOAS, vol. LVII, 1994, pp. 516-550, figs 1-14 (1 town plan and 24 architectural drawings) pls. 1-16 (32 photographs).

‘One day he [Ghiyath al-din Tugluq] was accompanying Sultan

Qutb al-din [Mubarak Shah] and pointed to the site and said

“O Lord of the World how good it would be if a city could be

built there”. The sultan replied sharply: “build it when you are

the sultan”. As God willed it he did become the sultan, built the

city and named it after himself'.

The fourteenth-century traveller, Ibn Battuta.

Many years ago a colleague commented to the Shokoohys that their work was on such out of the way places that it was hard to dispute, as hardly anyone else in the field had seen the locations, let alone written on them, and why did they not look into somewhere more familiar? The challenge was irresistible. Tughluqabad is nine miles to the south-east of the capital, Delhi, and its towering fortifications dominate the landscape. The project to survey it was launched in 1984.

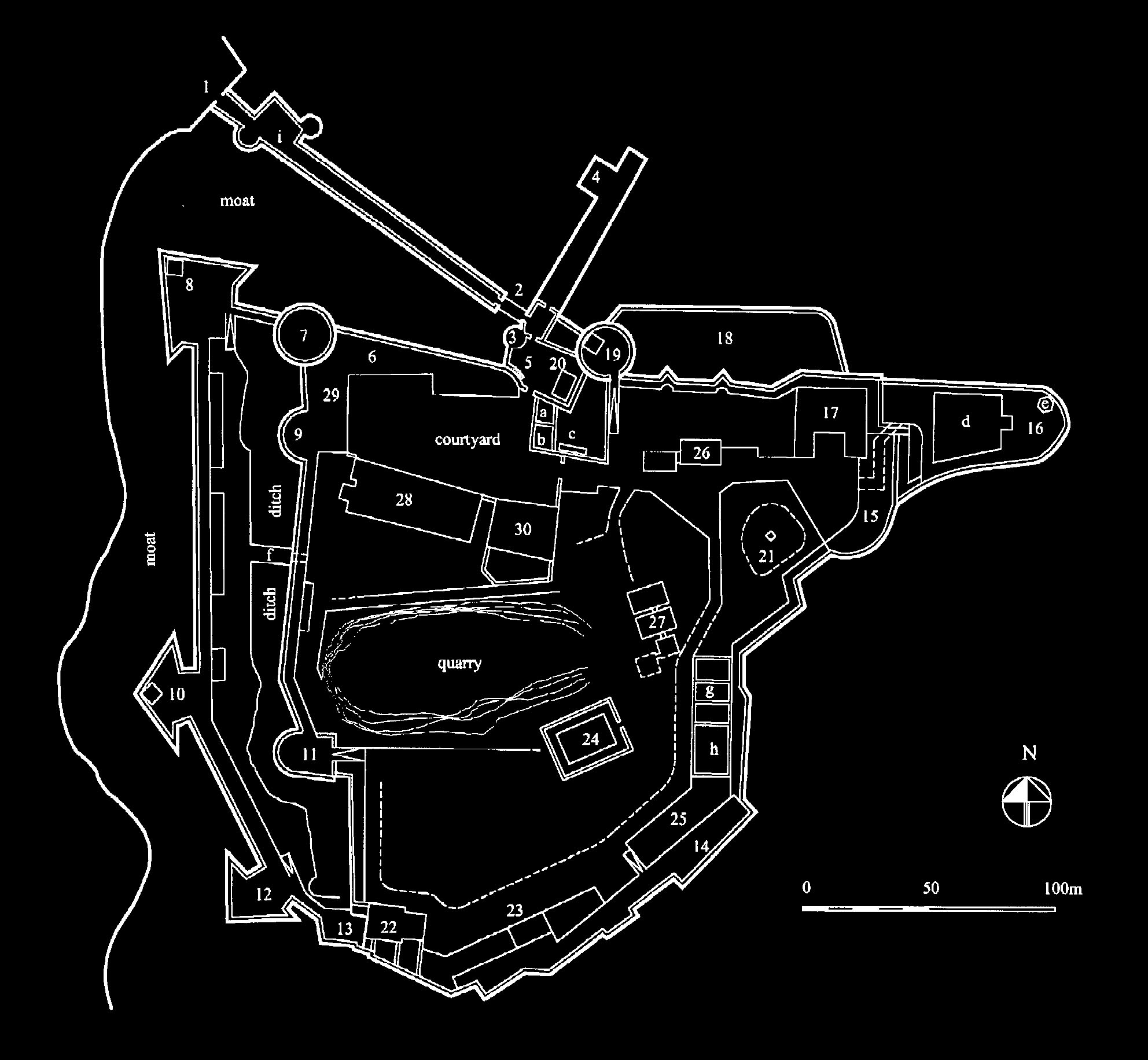

This first report took the neglected site, where the early-fourteenth century capital remains in a time capsule after its abandonment, and gives a town plan based on an aerial survey of 1946, before modern accretions. The public palaces and other structures in the fort are discussed, and sketches of the ruins of the well-known jahan nama, a pavilion over the private palaces in the Citadel are given. In the town the paper considers the ruins of a house and the substantial Jami`, the congregational mosque, with reconstruction drawings suggesting its original form. Many of the drawings, including the town plan, were work in progress and are superseded by more detailed and accurate drawings as the project continued, with second and third interim reports in BSOAS, an article in UDS, V, on the planning of Tughluqabad and its divergence from traditional Hindu urban forms, and in 2007 the final report as a monograph: Tughluqabad, a paradigm for Indo-Islamic urban planning and its architectural components.

.jpg?791) * “Sasanian royal emblems and their re-emergence in the fourteenth-century Deccan” M. Shokoohy, Muqarnas, XI, 1994, pp. 65-78, figs. 1-21 (3 engravings, 7 drawings, 11 photographs).

* “Sasanian royal emblems and their re-emergence in the fourteenth-century Deccan” M. Shokoohy, Muqarnas, XI, 1994, pp. 65-78, figs. 1-21 (3 engravings, 7 drawings, 11 photographs).

ISSN: 0921-0326

ISBN: 978-9-004259-31-7

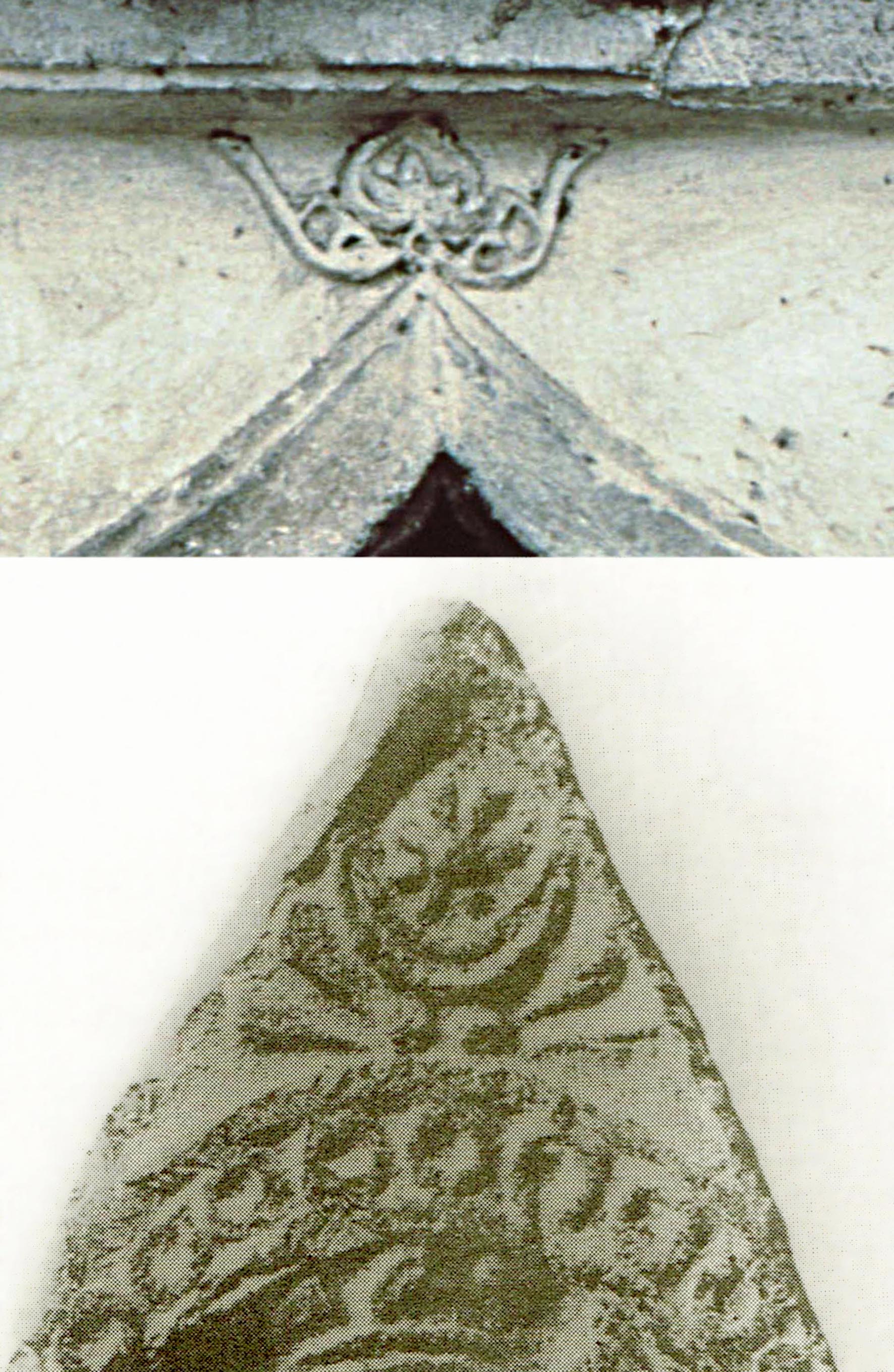

The necropolis of the early Bahmani sultans at Gulbarga

displaying variations of a device composed of a pair of

wings below a crescent moon, in some cases encircling

a disc which occasionally bears the word Allah.

The Bahmani dynasty of the fourteenth century Deccan in central India claimed descent from the pre-Islamic Sasanian dynasty of Iran. The Bahmanis decorated the crowns of the arches of their monuments with a curious device, which varies in detail but has a crescent or disc flanked by open wings, closely resembling the emblems on the crowns of the Sasanian emperors. The crest appears on the buildings of several early Bahmani sultans, who perceived that their claim to royal ancestry would reinforce their legitimacy to the throne, but as they consolidated their power, the device became transfigured gradually to a simple decorative feature, and during the following dynasty – the `Adil Shahis – evolved as two wings or two large triangular forms filling up the space above the arch.

Investigation of the roots of the form from ancient Iran to the Sasanian crowns prompts the argument that that although the device appears on the crowns of Sasanian emperors on all their coins, it is unlikely that the Bahmanis would have taken their emblem from coinage, as if they had seen the coins – found in large numbers even today – they would not relate the device to the arches of buildings. Another thread is, therefore, investigated, presenting historic and archaeological evidence of such a device appearing over the arches of the Sasanian buildings and even on some early Muslim structures.

Investigation of the roots of the form from ancient Iran to the Sasanian crowns prompts the argument that that although the device appears on the crowns of Sasanian emperors on all their coins, it is unlikely that the Bahmanis would have taken their emblem from coinage, as if they had seen the coins – found in large numbers even today – they would not relate the device to the arches of buildings. Another thread is, therefore, investigated, presenting historic and archaeological evidence of such a device appearing over the arches of the Sasanian buildings and even on some early Muslim structures.

A coin of the Sasanian Emperor Khusraw II showing the emperor wearing a crown topped with a pair of wings, the crescent moon and a star. On the crown of earlier Sasanian emperors a disc or globe is presented instead of the star.

In the fourteenth century Sasanain ruins would have been commonplace in Iran and Central Asia, the homeland of the Bahmani family, and it would have been from these buildings that they adopted their concept, perhaps unaware of the symbolic meaning of each of the Zoroastian features: the wings representing God (Ahura Mazda), and the crescent and disc the divine beings Anahita and Mithra.

In the fourteenth century Sasanain ruins would have been commonplace in Iran and Central Asia, the homeland of the Bahmani family, and it would have been from these buildings that they adopted their concept, perhaps unaware of the symbolic meaning of each of the Zoroastian features: the wings representing God (Ahura Mazda), and the crescent and disc the divine beings Anahita and Mithra.

Above: a version of the Bahmani motif over

the arch of a shop in the bazaar of the fort

of Gulbarga, and below: an old photograph of

a Sasanian ossuary, representing an arched

portal with a device similar to that on the crown

of the Sasanian emperors.

“Kirtipur: Cultural traditions under siege”, M. Shokoohy, UDS, I, 1995, pp. 125-132, figs. 12.1-12.7.

ISBN: 978-1-870606-04-2

ISSN: 1358-3255

The nature of the town of Kirtipur, and the relationship of the population with urban space was the primary focus of the project initiated at the University of Greenwich in 1985 resulting in the publication of Kirtipur, An Urban Community in Nepal, and continuing until 2014 with the book Street Shrines of Kirtipur.

The nature of the town of Kirtipur, and the relationship of the population with urban space was the primary focus of the project initiated at the University of Greenwich in 1985 resulting in the publication of Kirtipur, An Urban Community in Nepal, and continuing until 2014 with the book Street Shrines of Kirtipur.

In this early report on the Greenwich project, an explanation is given of how the focal points of the neighbourhoods, the Buddhist and Hindu temples and shrines, which share the architectural traditions of other Kathmandu Valley towns, define the neighbourhoods and how the temples and shrines are incorporated in the many and varied processional routes for religious festivals and joyous occasions as well as the particular routes for funerals through the town.

Deo Dhoka Tole with its traditional dwellings still standing in 1986, but many collapsed some years later, probably undermined by an earthquake in 1988. They were reconstructed in later years with no reference to the traditional architecture of the town.

The spiritual aspect of life is not confined to formal worship and dominates all aspects of the daily life of the townspeople. The sacred territory of the family is the house, and its arrangement is understood in terms of a complex symbolism, with the house taking its roots in the underground world, rising up to the earth, where people live, and pointing towards the celestial regions. The construction materials and other elements too have their own symbolism, and spiritual considerations also regulate the practical use of a dwelling, according to a vertical hierarchy. The importance attached to these considerations and to living in the ancestral home have an essential role in the way the houses are used and extended, and the density of housing. However, the traditions are fluid, and the impact of modern ways of life and the proximity of the capital, Kathmandu are challenging the old norms. Another report “Social effects of land use changes in Kirtipur, Nepal” (UDS, III, 1997) considers our follow-up study of the physical, morphological and social changes which are taking place rapidly in Kirtipur.

The spiritual aspect of life is not confined to formal worship and dominates all aspects of the daily life of the townspeople. The sacred territory of the family is the house, and its arrangement is understood in terms of a complex symbolism, with the house taking its roots in the underground world, rising up to the earth, where people live, and pointing towards the celestial regions. The construction materials and other elements too have their own symbolism, and spiritual considerations also regulate the practical use of a dwelling, according to a vertical hierarchy. The importance attached to these considerations and to living in the ancestral home have an essential role in the way the houses are used and extended, and the density of housing. However, the traditions are fluid, and the impact of modern ways of life and the proximity of the capital, Kathmandu are challenging the old norms. Another report “Social effects of land use changes in Kirtipur, Nepal” (UDS, III, 1997) considers our follow-up study of the physical, morphological and social changes which are taking place rapidly in Kirtipur.

The toles, or clusters of related houses of Kirtipur provide the space

for families of the neighbourhood to interact, while getting on with

everyday occupations: washing and drying laundry, bathing, or

processing the harvest. The street shrines in the toles are a focus

for daily worship as well as marking the routes of the many religious

processions. This view of Tanini Tole taken in 1986 shows how the

houses still preserved their traditional form, but in the following

decade many were altered with additions and reconstructions.

“Epitaphs of Kayalpatnam, South India”, M. Shokoohy, SAS, vol. XI, 1995, pp. 121-128, figs 1-7.

Kayalpatnam means “Kayal city", but the town was not recognised by scholars as the famous ancient Qa'il, visited by many early travellers. Influenced by the views of Robert Caldwell, Coadjutor Bishop of Madras, and regarded an authority on South Indian history early in the twentieth century, even Henry Yule, while noting in his edition of Marco Polo that "Kayalpatnam must in all probability be the place", still published Caldwell's dismissive comment: "There are no relics of ancient greatness in Kayalpattanam and no traditions of foreign trade, and it is admitted by its inhabitants to be a place of recent origin, which came to existence after the abandonment of the true Kayal. They state also that the name of Kayalpattanam has only recently been given to it, as a reminiscence of the older city”.

Kayalpatnam means “Kayal city", but the town was not recognised by scholars as the famous ancient Qa'il, visited by many early travellers. Influenced by the views of Robert Caldwell, Coadjutor Bishop of Madras, and regarded an authority on South Indian history early in the twentieth century, even Henry Yule, while noting in his edition of Marco Polo that "Kayalpatnam must in all probability be the place", still published Caldwell's dismissive comment: "There are no relics of ancient greatness in Kayalpattanam and no traditions of foreign trade, and it is admitted by its inhabitants to be a place of recent origin, which came to existence after the abandonment of the true Kayal. They state also that the name of Kayalpattanam has only recently been given to it, as a reminiscence of the older city”.

This view confused later reports, even the Imperial Gazetteer of India – where two entries appear, under Kayal and Kayalpatnam – as well as that of Sayyid Yusuf Kamal Bukhari, who published two Muslim epitaphs of Kayalpatnam, noting the town as a small port in the Tinnevelly District, but not to be confused with the historic Qa'il.

Tombs of personages who lived in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth century, in

the tomb chamber attached to the smaller congregational mosque (Jamiʽ al-saghir).

Caldwell’s view, in spite of claiming that he had spent some time in Kayalpatnam, ignored the townspeople’s belief that their town is the same as Qa'il and their veneration of the shrines of their Sufi saints, some of whom are believed to have settled there as early as the twelfth century. Moreover, if Caldwell had examined Kayalpatnam itself he could not have missed the numerous old tombstones in the graveyards attached to the mosques, inescapable to even an untrained eye.

Caldwell’s view, in spite of claiming that he had spent some time in Kayalpatnam, ignored the townspeople’s belief that their town is the same as Qa'il and their veneration of the shrines of their Sufi saints, some of whom are believed to have settled there as early as the twelfth century. Moreover, if Caldwell had examined Kayalpatnam itself he could not have missed the numerous old tombstones in the graveyards attached to the mosques, inescapable to even an untrained eye.

To set the record straight the paper examines some of the fifteenth and sixteenth century epitaphs, giving their texts and discussing the history of the named personages. These epitaphs, together with an inscription in the larger of the two congregational mosques giving the date of the building as AH 737/AD 1336-7 and also the late fourteenth and early fifteenth-century epitaphs in a shrine known as the Seven Martyrs are indisputable evidence of the continuous life of the town and re-establish Kayalpatnam and its monuments in their rightful place in history. A comprehensive account of the city is given in Muslim Architecture of South India.

Two epitaphs in the Jamiʽ al-saghir tomb chamber: (left) dated 9 Dhi’l-hijja

806 (18 June 1404) and (right) 4 Shawwal 811 (20 February 1409).

Entries in The Grove Dictionary of Art, (ed. Jane Shoaf Turner) 34 vols, Macmillan, London-New York, 1996.

Entries in The Grove Dictionary of Art, (ed. Jane Shoaf Turner) 34 vols, Macmillan, London-New York, 1996.

ISBN: 978-1-884446-00-9 Available by subscription from www.oxfordartonline.com

The entries on Indo-Islamic architecture, and on some major towns of Muslim origin in India for the Grove Dictionary of Art are written by the Shokoohys. PDFs of these papers are not currently available.

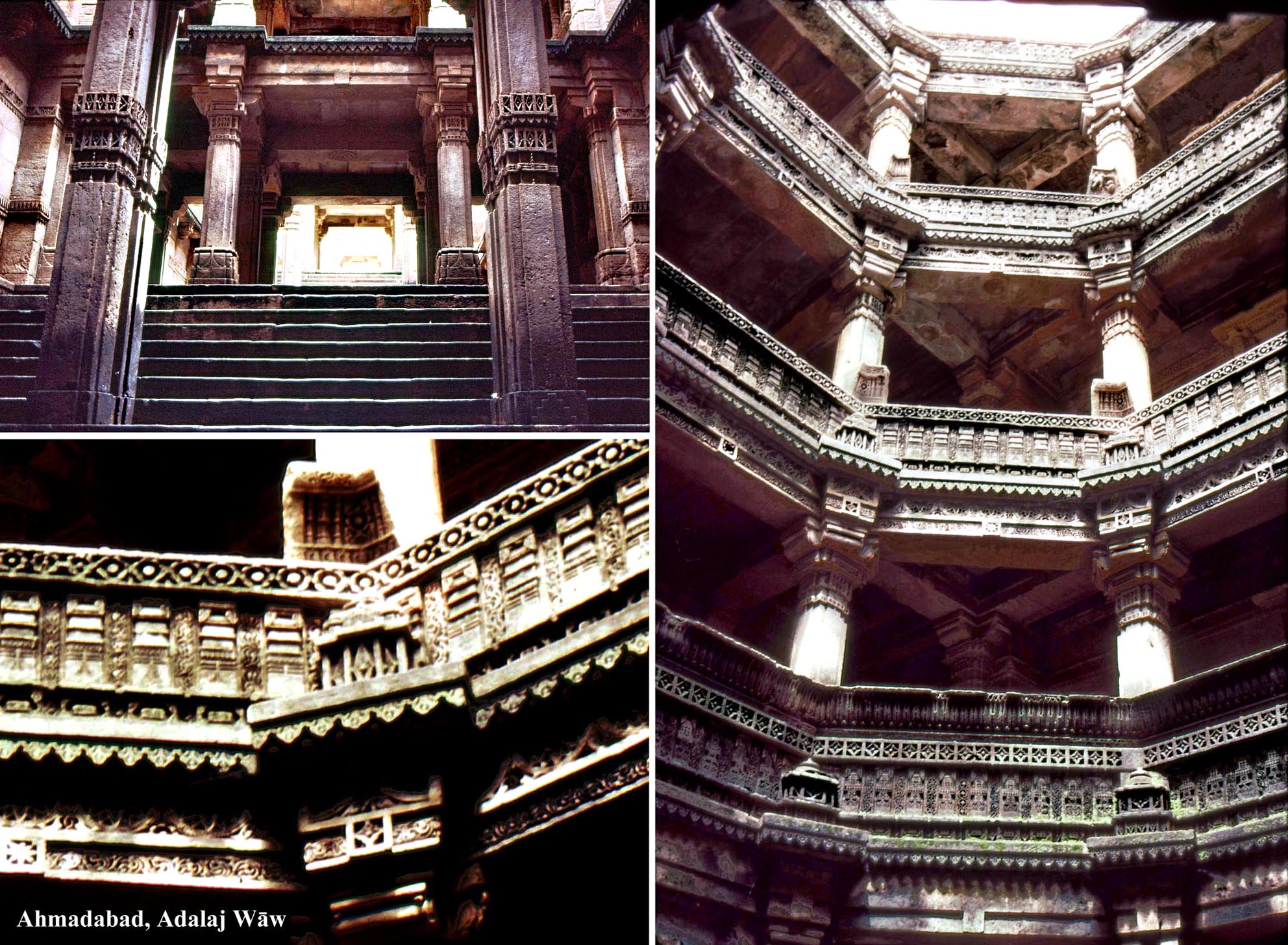

The marriage between Muslim architecture and traditional Hindu and Jain building methods is best displayed in Gujarat. The fifteenth-century Bai Harir Wav (step-well and reservoir) is not only built using traditional structural methods, but has carvings based on old Indian motifs.

.jpg?12) Entries written jointly by M & N. H. Shokoohy:

Entries written jointly by M & N. H. Shokoohy:

“Indian Subcontinent, 11th-16th century, (b) North India (sultanates)”, vol. XV, pp. 338-346;

“Indian Subcontinent, 11th-16th century, (c) West (Gujarat and Nagaur)”, vol. XV, pp. 346-351;

“Indian Subcontinent, 11th-16th century, (d) East (Bengal)”, vol. XV, pp. 351-353;

“Indian Subcontinent, 11th-16th century, (e) Central (Malwa)”, vol. XV, pp. 353-355;

The short-lived sultanate of Malwa, established after the fall of the Tughluq dynasty, took the

traditions of Delhi architecture and refined them further by employing inlaid marble. The audience

hall known as Hindola Mahal is exceptional among sultanate halls in having survived intact. It

follows the principles of Tughluq audience halls, but, unlike that of Tughluqabad, is free-standing.

The battered walls also follow Tughluq forms.

_court.jpg?12) The following entries by M. Shokoohy:

The following entries by M. Shokoohy:

“Indian Subcontinent, 6th-11th century, (b) West (Bhadresvar)”, vol. XV, pp. 308-9;

“Indian Subcontinent, 11th-16th century, (f) South (Deccan)”, vol. XV, pp. 355-358 “(Kerala and Tamil Nadu)” 355-359;

“Chanderi”, vol. VI, p. 444;

“Mandu”, vol. XX, pp. 250-251.

Chanderi, a border town of the sultanate of Malwa was eventually annexed to the Mughal empire by Akbar and many buildings of the town, including private houses, some on a grand scale, date from the Mughal period. Kamal Singh’s house is a good example, retaining its original features, including the public court (below) and private court (above).

.jpg?12) The following entries by N. H. Shokoohy:

The following entries by N. H. Shokoohy:

“Indian Subcontinent, 6th-11th century, (ii) Indo-Islamic”, vol. 15, 306-7, “(a)

North-West (Sind)”, vol. 15, 307;

“Indian Subcontinent, 11th-16th century, (ii) Indo-Islamic”, vol. 15, 336-7, “(a)

North-West (Multan - East Punjab)”, vol. 15, 337-8;

“Jaunpur”, vol. 17, 451

“Multan”, vol. 22, 279

The Sharqi kingdom of Jaunpur came to a violent end when the Delhi Sultan Sikandar Lodi took

over the town and destroyed it except for a few mosques. Nevertheless, the surviving monuments

demonstrate the development of a local architecture relating to both Delhi and Bengal. The Atala

Masjid (1377-1404 AD) built incorporating temple spoil, but with a massive central screen three

times higher than the colonnaded prayer hall, marks a new style adopted in later buildings.

* “Social effects of land use changes in Kirtipur, Nepal” M. and N. H. Shokoohy and Uttam Sagar Shrestha, UDS, III, 1997, pp. 51-74, figs. 3.1–3.24.

* “Social effects of land use changes in Kirtipur, Nepal” M. and N. H. Shokoohy and Uttam Sagar Shrestha, UDS, III, 1997, pp. 51-74, figs. 3.1–3.24.

ISBN: 978-1-870606-05-9

ISSN: 1358-3255

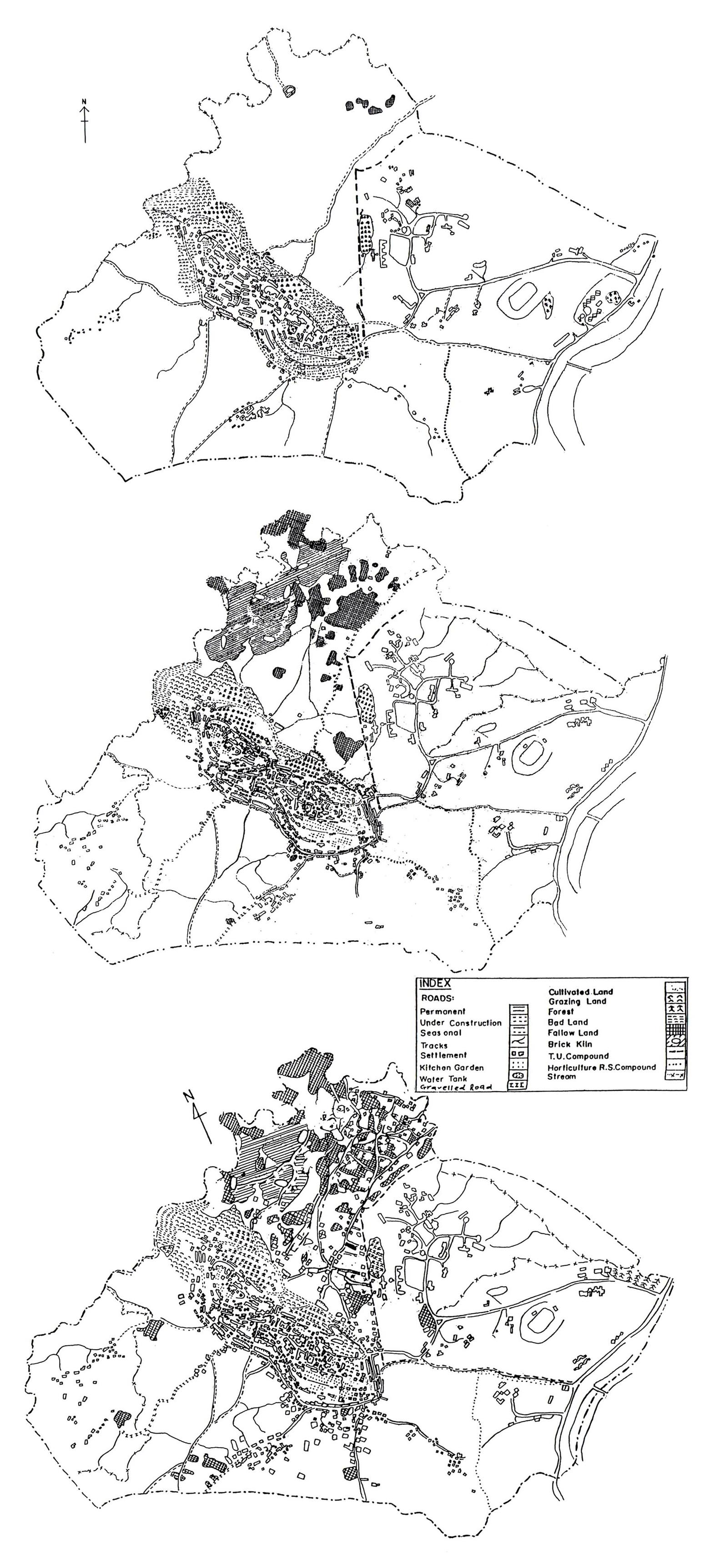

The rapid changes in society in Kirtipur linked to alterations in land use in the 1990s are not discussed in other books and papers concerning the town. The relatively static medieval type of society that existed in Nepal until the 1950s had been challenged when a motorable road link from India made modern facilities available to the country. Over the years, changes in local government along with the development of the capital and the nearby Tribhuvan University in the late 1970s altered the balance between the cultivated and built-up areas of Kirtipur, then a small agricultural town close to the capital. The changes are documented, explaining how the town, once strategically located on a trade route, had retained, in spite of invasion, earthquakes, and neglect, much of its mediaeval layout and traditional way of life. The temples, houses and kitchen gardens were clustered mainly on an outcrop of rock within the walls, further protected by a band of woodland, maximising the defensive potential of the site, and reserving the surrounding fertile land for agriculture. The study of land use in recent decades reveals a gradual densification and expansion of the historic core, a reduction in the area of kitchen gardens and woodland, and much new housing along roads and tracks to the town.

The drastic reduction in cultivated land occurred with the acquisition of about 40% of the town’s farmland by Tribhuvan University and the Horticultural Research Station in 1957, exacerbated by an increase in fallow and bad lands from the 1980s as a result of land speculation and the development of brick kilns to feed new construction. Much of this land was then built over, but without facilities and infrastructure.

The land use maps of 1981, 1989 and 1996 show not only a large proportion of the agricultural land, mainly rice paddy, taken over by the then newly established university campus, but also the extreme effects of property speculation, resulting in paddy being first left fallow, and then sold off as building plots.

The sudden change to “democratic” rule in 1990, while not as harsh as the experience in the former Soviet Union, was nevertheless characterised by a period of uncertainty in government, and a free-for-all atmosphere in which building and planning controls were flouted, land changed hands, and, in the case of Kirtipur, a large proportion of the remaining agricultural land became building plots. Social aspirations, changes of occupation and mobility, perceptions of the expected results of development as against the reality, and the use of money derived from land sales are documented and discussed along with the town’s potential for arresting typical third-world urban sprawl.

The sudden change to “democratic” rule in 1990, while not as harsh as the experience in the former Soviet Union, was nevertheless characterised by a period of uncertainty in government, and a free-for-all atmosphere in which building and planning controls were flouted, land changed hands, and, in the case of Kirtipur, a large proportion of the remaining agricultural land became building plots. Social aspirations, changes of occupation and mobility, perceptions of the expected results of development as against the reality, and the use of money derived from land sales are documented and discussed along with the town’s potential for arresting typical third-world urban sprawl.

A 1994 photograph shows new buildings beginning to emerge in the

paddy fields. In later years most fields were built over. The loss of

agricultural land has altered the economy of the town and made the

once agricultural community enter the employment market in the

nearby capital, Kathmandu.

* “The Safa Masjid at Ponda, an architectural hybrid”, M. Shokoohy, SAS, XIII, 1997, pp. 71-85, figs 1-13.

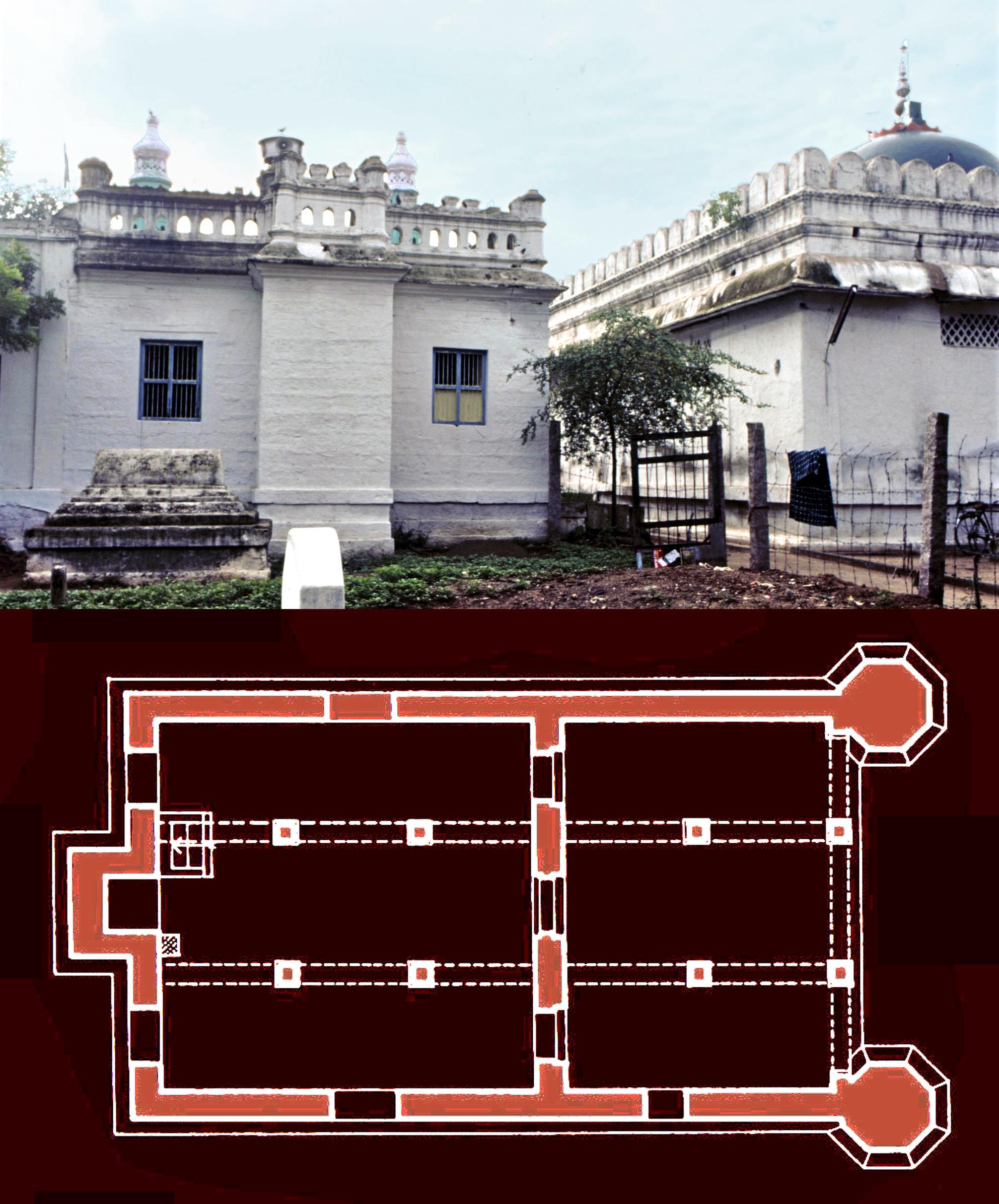

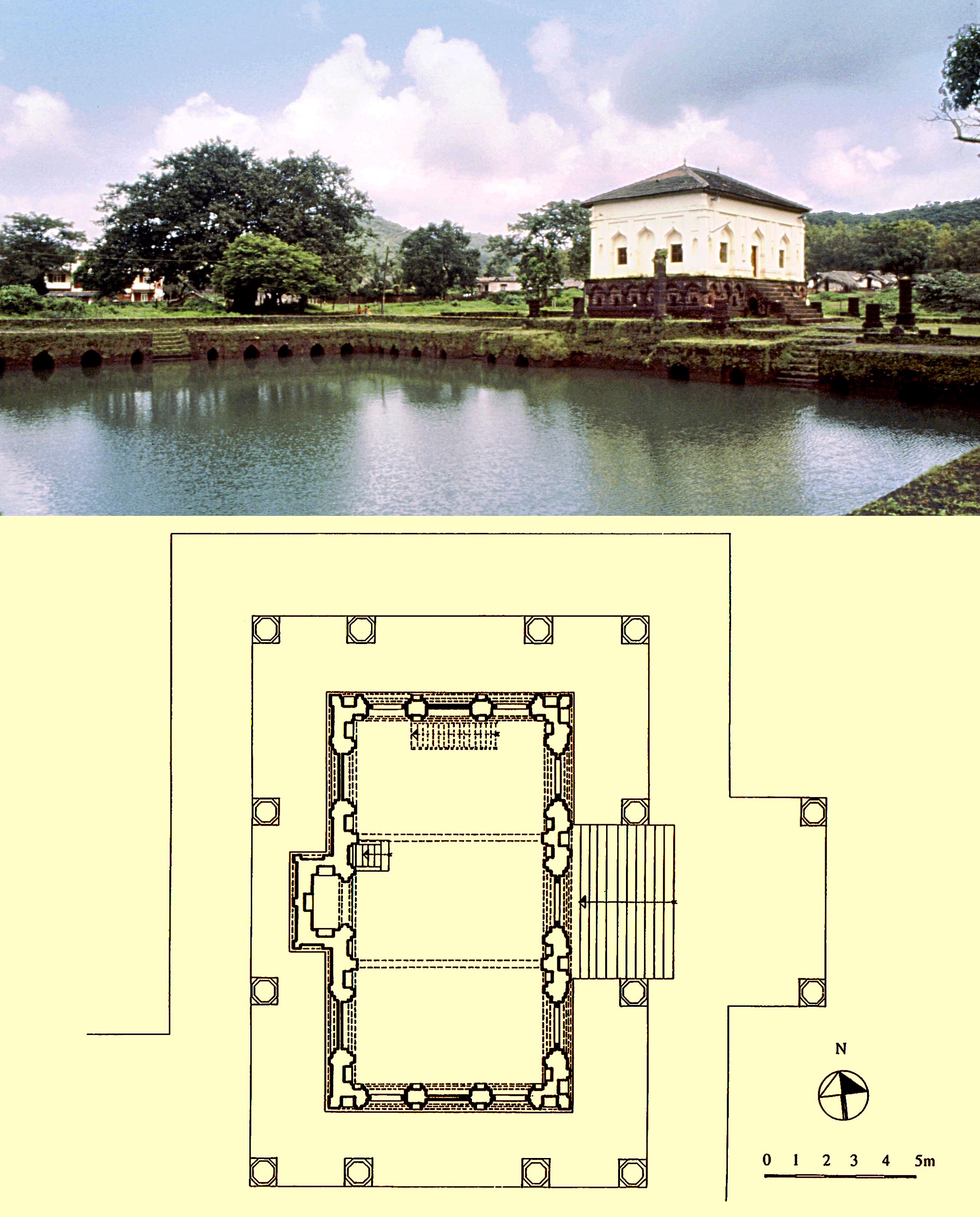

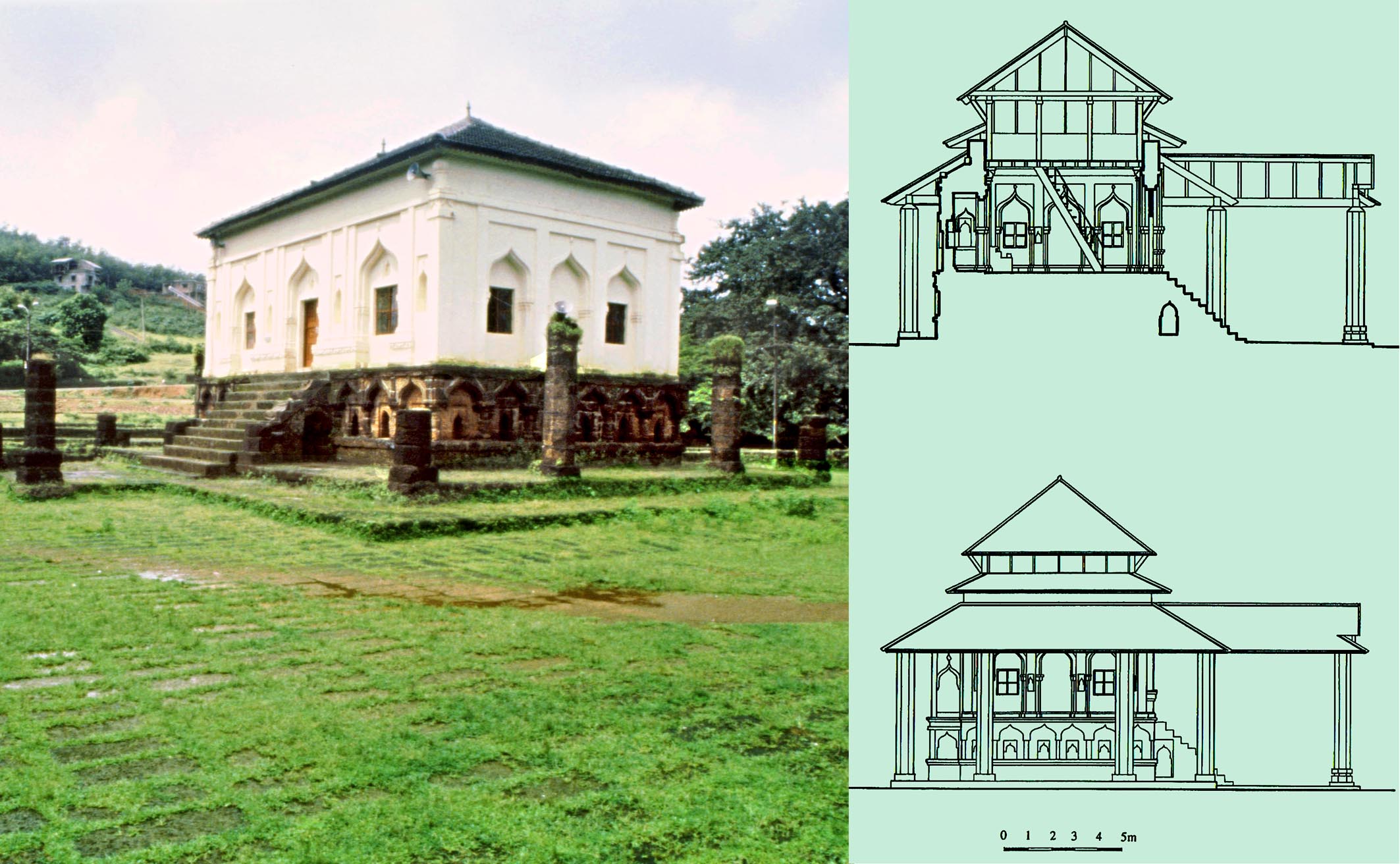

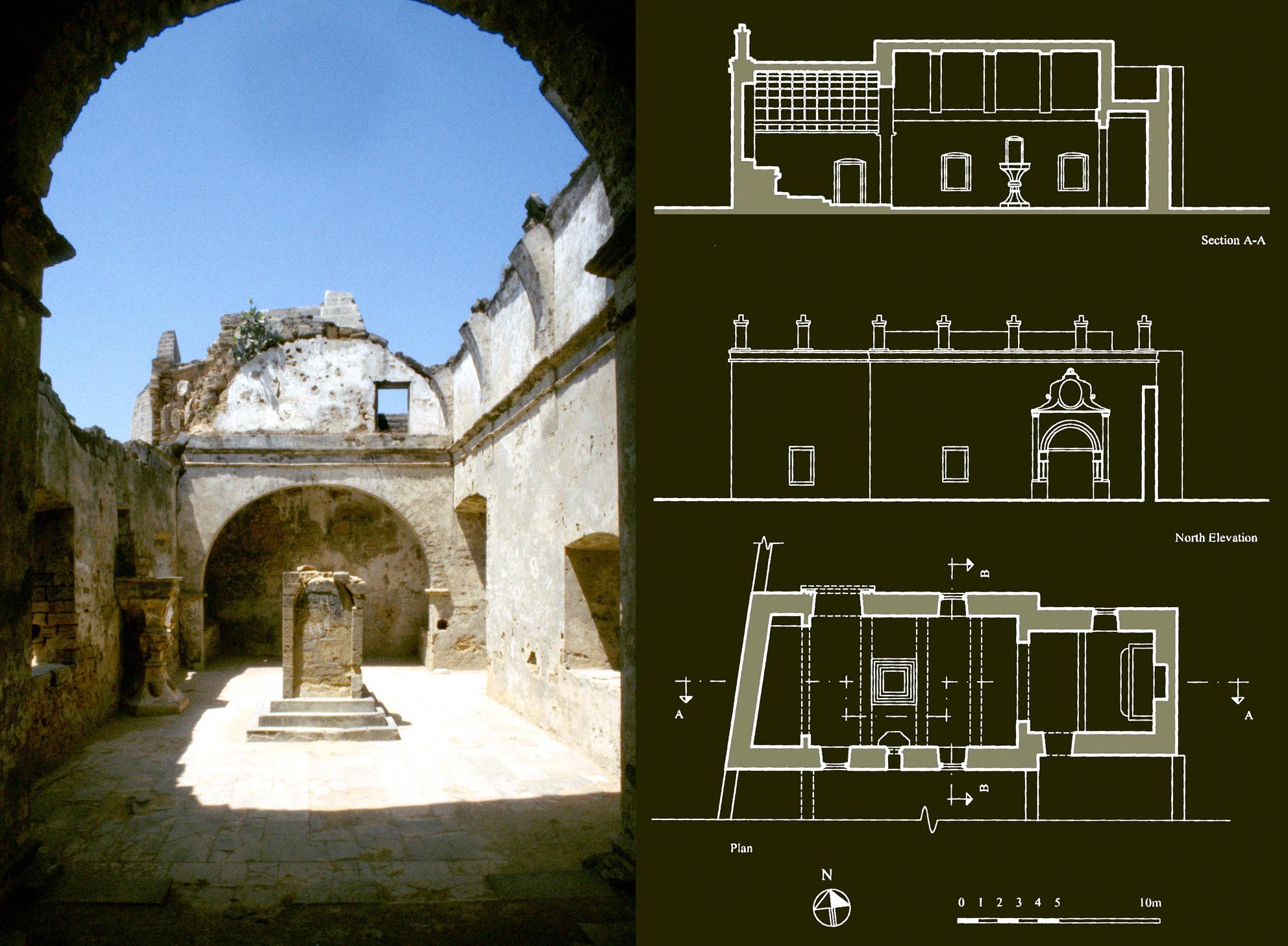

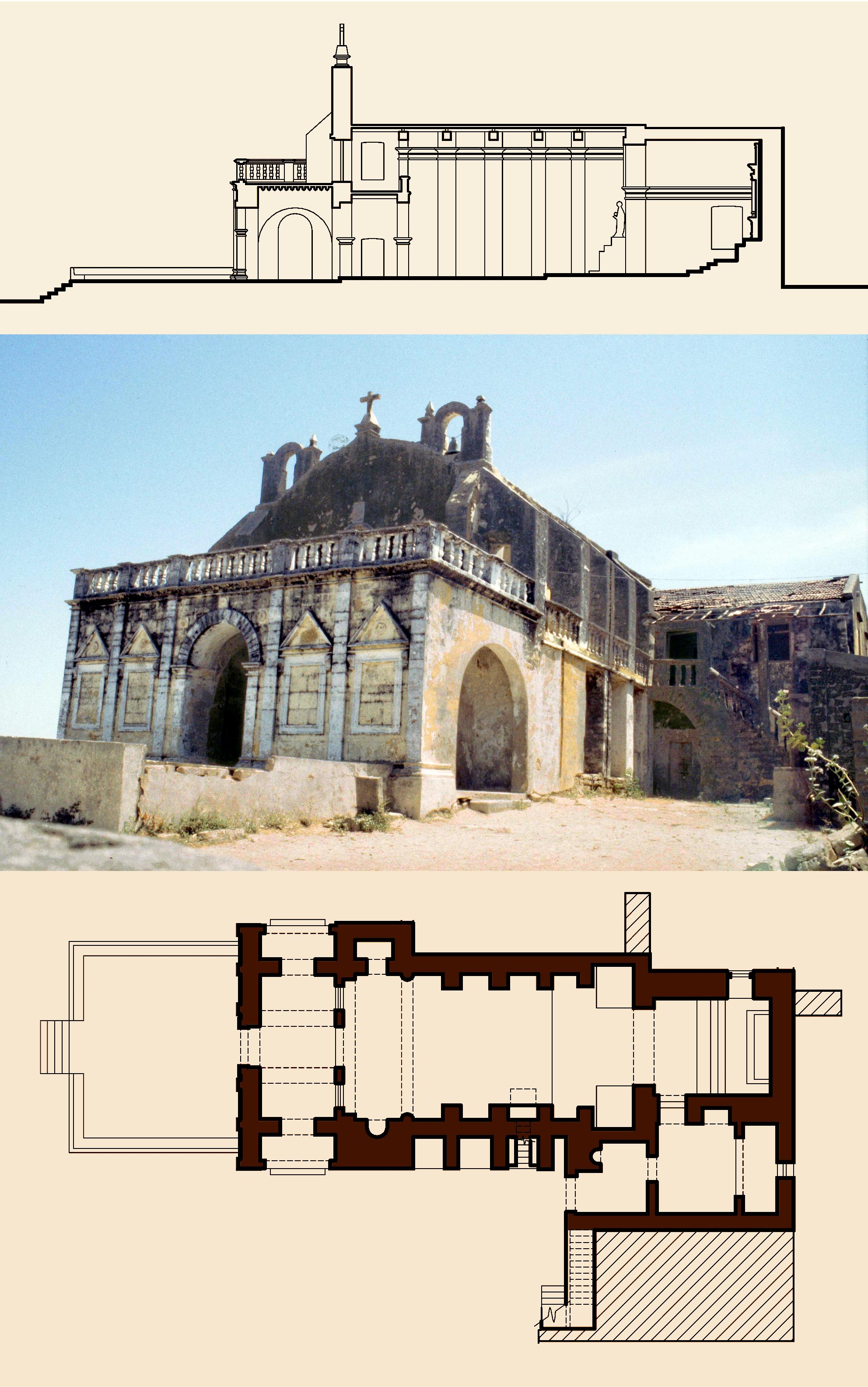

Among the mosques of the coastal towns of South India, the Safa Masjid at Ponda, in the State of Goa, is a curious example, as it is follows neither the style of the buildings of the Muslim settlers of Malabar (the south-western seaboard) nor that of the mosques of the Deccan, which included Ponda before it was taken by the Portuguese in 1763. The mosque is set on a high plinth, and has doors, windows and niches with pointed arches in what might be called a "Deccani" style, but the configuration of its prayer chamber surrounded by a colonnade, as well as the light structure of its wooden roof conforms with the building methods of the Malabar mosques. Its exceptional form alone makes it worthy of investigation, even more so in view of its survival in an area long under the Portuguese, characterised as dedicated enemies of the Muslims, and destroyers of Muslim buildings wherever they found them in South India.

Among the mosques of the coastal towns of South India, the Safa Masjid at Ponda, in the State of Goa, is a curious example, as it is follows neither the style of the buildings of the Muslim settlers of Malabar (the south-western seaboard) nor that of the mosques of the Deccan, which included Ponda before it was taken by the Portuguese in 1763. The mosque is set on a high plinth, and has doors, windows and niches with pointed arches in what might be called a "Deccani" style, but the configuration of its prayer chamber surrounded by a colonnade, as well as the light structure of its wooden roof conforms with the building methods of the Malabar mosques. Its exceptional form alone makes it worthy of investigation, even more so in view of its survival in an area long under the Portuguese, characterised as dedicated enemies of the Muslims, and destroyers of Muslim buildings wherever they found them in South India.

The history of the region and the mosque is investigated, with a full survey of the building together with reconstruction drawings suggesting its original form. It appears that it originally had a two-tiered timber roof structure and in general appearance would have conformed to the local architectural norms of this coastal region of South India. Nevertheless, the unusually high plinth of the prayer hall, the decorative niches and the ogee form of their arches would have been a reminder that the town is within the territory of the Deccan: in short, a reference to the authority of the sultanate in a traditional structure.

The diminutive Safa Masjid was probably built together with a large adjacent reservoir. Tanks of this kind are usually associated with temples, but in the fourteenth century Ibn Battuta mentions that at the congregational mosque of Jurfatan (at or near Cannanor): “There is a large reservoir five hundred feet long and three hundred wide, constructed with red stone, around it were twenty eight domes (apparently chatris) each with four platforms and stone stairs… next to the reservoir is the Jamiʽ mosque of the Muslims with a set of steps connecting it to the reservoir”.

While the local attribution of a 1560 (AH 968-9) date is uncertain, the Deccani influence in the decoration of the mosque, and the lack of features specifically associated with the independent trading communities of the coasts – semi-circular arches, or a prayer niche with a semi-circular plan – attest to it having been constructed when the area was firmly under the Deccan sultanate and therefore of the mid-fifteenth to mid-sixteenth century and certainly not later than the seventeenth.

While the local attribution of a 1560 (AH 968-9) date is uncertain, the Deccani influence in the decoration of the mosque, and the lack of features specifically associated with the independent trading communities of the coasts – semi-circular arches, or a prayer niche with a semi-circular plan – attest to it having been constructed when the area was firmly under the Deccan sultanate and therefore of the mid-fifteenth to mid-sixteenth century and certainly not later than the seventeenth.

The reconstruction drawings have been superseded by those given in Muslim Architecture of South India where the mosque and its adjoining substantial tank are discussed in more detail.

The Safa Masjid and some of the final reconstruction drawings

as presented in Muslim Architecture of South India.

* “The town of Cochin and its Muslim heritage on the Malabar coast, South India”, M. Shokoohy, JRAS, Series 3, VIII, 1998, pp. 351-394, figs 1-15, pls 1-19.

Among the cities of South India Cochin is popular with tourists. They walk south along Bazaar Road, with its antique and knick-knack shops along with wholesalers of imported goods and merchants’ offices, visit the Synagogue of the “White Jews”, miss that of the “Black Jews”, walk south a little more to see the Old Palace and Museum and terminate their journey. Some may also take in the north of the island and the site of the old European forts ‒ one built on the site of the other ‒ where the much modernised historic churches are found. Few, if any, go south of the palace to the end of Jew Town Road to enter the Muslim quarter with its magnificent sixteenth-century mosque and other monuments.

Among the cities of South India Cochin is popular with tourists. They walk south along Bazaar Road, with its antique and knick-knack shops along with wholesalers of imported goods and merchants’ offices, visit the Synagogue of the “White Jews”, miss that of the “Black Jews”, walk south a little more to see the Old Palace and Museum and terminate their journey. Some may also take in the north of the island and the site of the old European forts ‒ one built on the site of the other ‒ where the much modernised historic churches are found. Few, if any, go south of the palace to the end of Jew Town Road to enter the Muslim quarter with its magnificent sixteenth-century mosque and other monuments.

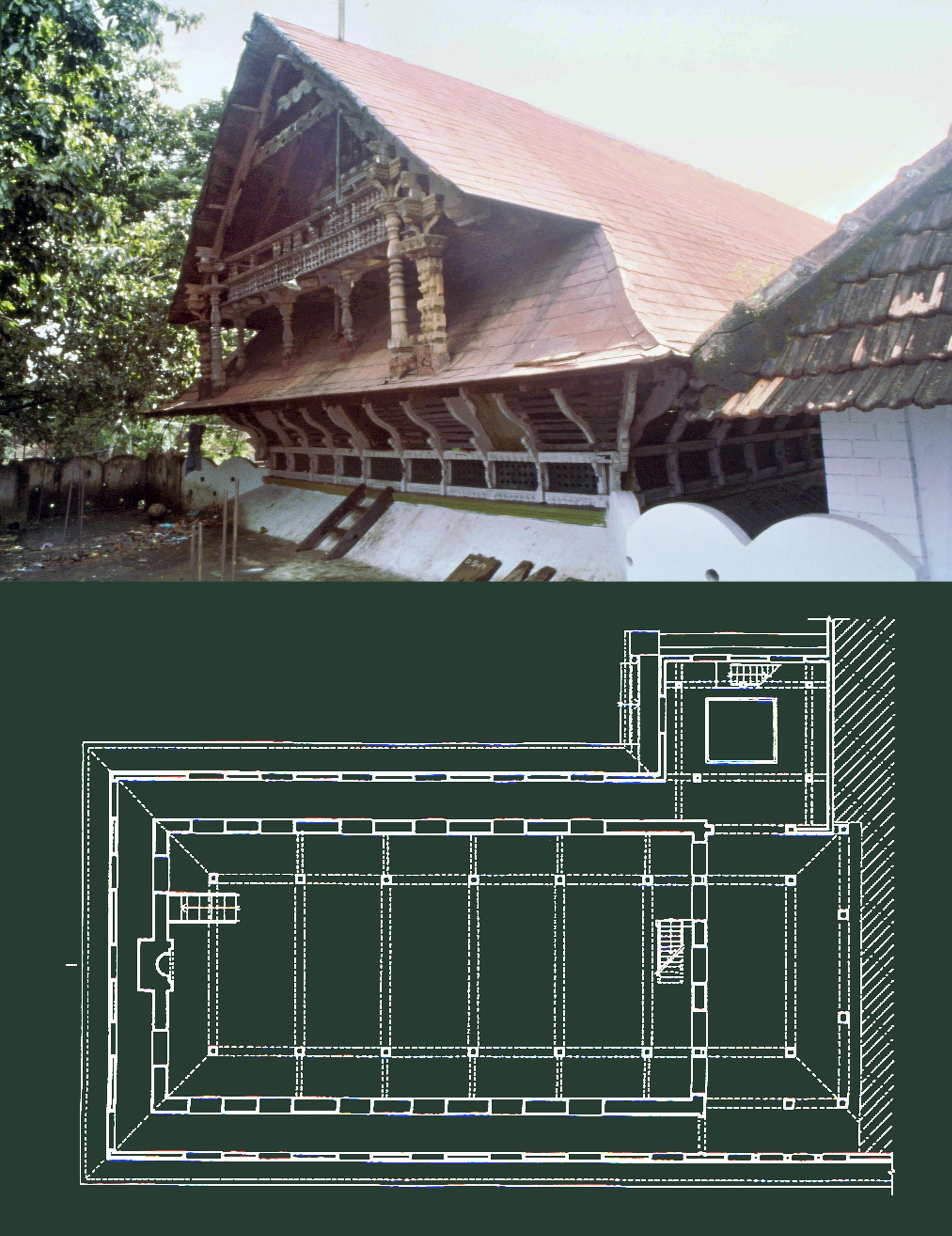

The paper introduced these monuments to the scholarly world and put them on the map. The large and impressive Shafe’i Jamiʽ mosque or Chembattapalli is one of the rare examples of a substantial South Indian mosque, which, in spite of some later additions, has survived without significant alteration. In its structure of plain but massive stone walls and wooden columns supporting a timber superstructure, the mosque displays the regional vernacular. The joinery is simple, even crude, but devised in a manner that the structural elements fit together and support each other in equilibrium, but are flexible and storm-resistant. Such skilful detailing is an indication that the builders were using well-attested methods, established over the centuries in response to the climate and locally available materials. The mosque bears a bilingual inscription: the Malayalam version records the renovation of the mosque in the year 180 of Puduvaipu, the local era of Cochin (AD 1520-21) and the Arabic version gives the date AH 926 (AD 1519-20), fixing the date to 1520.

In spite of a modern concrete hall added to the front of the Shafeʽi Jamiʽ or Chembattapalli, the original plan and structural details are almost entirely preserved.

Not far from the mosque are two other buildings of considerable age, both built over the tombs of local religious personages, and regarded as shrines. One of these, over the tombs of Sayyid Isma`il and Sayyid Fakhr al-din Bukhari, is located near the Jami`, and the other is the revered Dargah of Zain al-din, which together with its mosque is of considerable interest. Until recently Zain al-din’s shrine bore a number of religious inscriptions recorded in the paper, but which were dismantled and sold sometime before 2006. Zain al-din is a well-known local personage and is the ancestor of Shaikh Ahmad Zain al-din: the well-known author of the Tuhfat al-Mujahidin.

Not far from the mosque are two other buildings of considerable age, both built over the tombs of local religious personages, and regarded as shrines. One of these, over the tombs of Sayyid Isma`il and Sayyid Fakhr al-din Bukhari, is located near the Jami`, and the other is the revered Dargah of Zain al-din, which together with its mosque is of considerable interest. Until recently Zain al-din’s shrine bore a number of religious inscriptions recorded in the paper, but which were dismantled and sold sometime before 2006. Zain al-din is a well-known local personage and is the ancestor of Shaikh Ahmad Zain al-din: the well-known author of the Tuhfat al-Mujahidin.

Apart from the Muslim monuments, the rapidly disappearing Jewish community of Cochin is considered, as well as the history of the town from its earliest times to the dominance by first the Portuguese and later the Dutch and British. An extended and comprehensive account of Cochin may be found in Muslim Architecture of South India.

A view of the shrine of Zain al-din and its inscriptions,

still in situ in 1994. While the Arabic inscriptions are

Qur’anic or bear religious texts, the Malayalam and

Tamil texts bear a local date of Puduvaipu 84 (1425 AD).

* “The Dark Gate, the Dungeons, the royal escape route, and more, survey of Tughluqabad, second interim report”, M. and N. H. Shokoohy, BSOAS, LXII, part 3, 1999, pp. 423-461, figs 1-14, pls 1-11 (22 photographs).

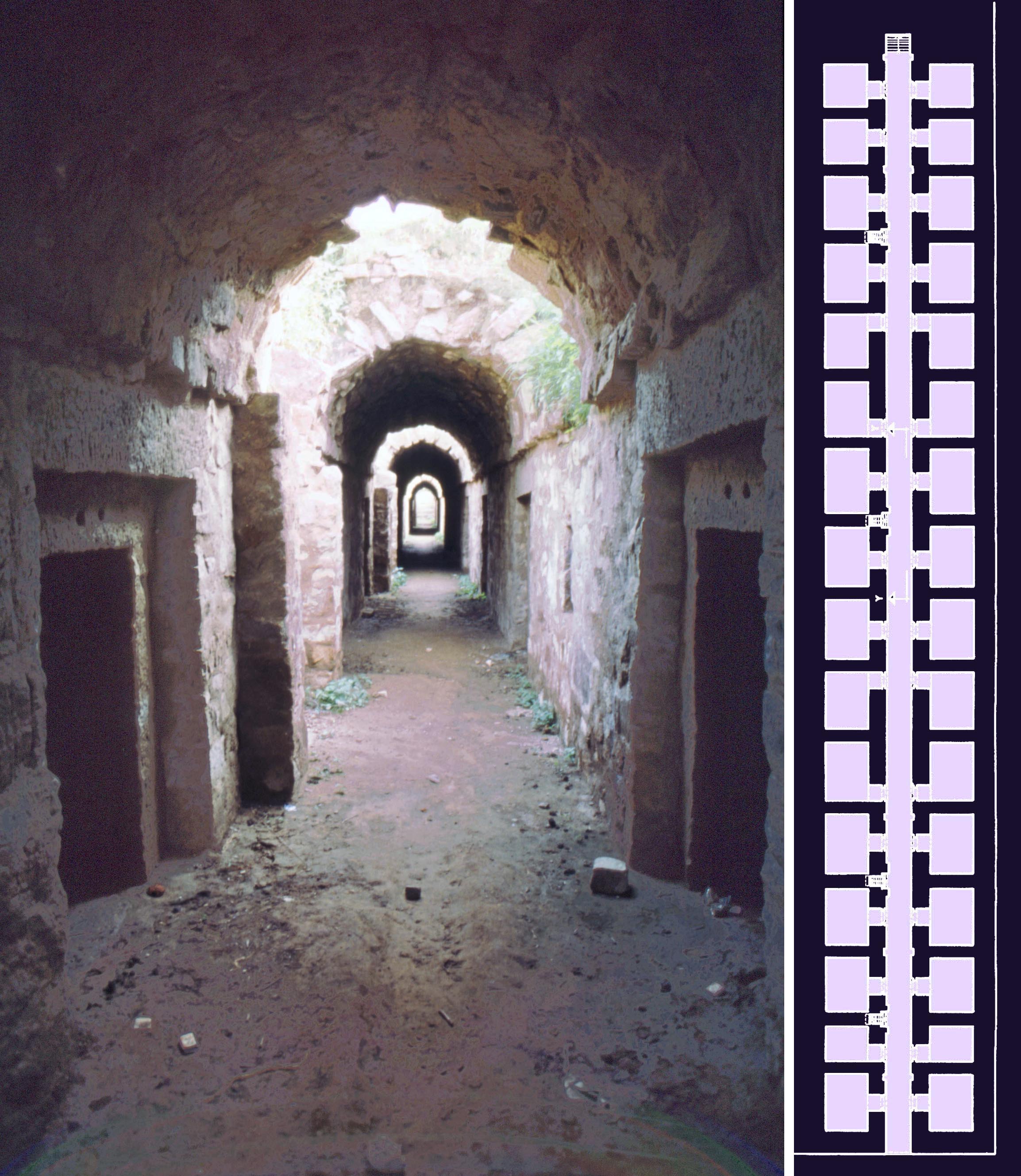

The citadel of Tughluqabad is the focus of the second report on the survey of Ghiyath al-din Tughluq’s capital. After its desertion on the death of the sultan the citadel was occupied for a short period in the late Mughal period and at first glance might appear to have retained little of the original Tughluq palaces. However, once the extent of the later occupation was investigated, the remains revealed many original features, including the massive platform of what had been the pavilion with a “golden” dome, described by Ibn Battuta. Rather than steps, the pavilion was accessed by ramps; these became a feature of later Tughluq palaces. Inside the platform a series of windowless and dark chambers with thick stone walls flanking a long corridor ‒ now referred to as “dungeons” ‒ were probably safe storerooms, perhaps of the treasury.

The citadel of Tughluqabad is the focus of the second report on the survey of Ghiyath al-din Tughluq’s capital. After its desertion on the death of the sultan the citadel was occupied for a short period in the late Mughal period and at first glance might appear to have retained little of the original Tughluq palaces. However, once the extent of the later occupation was investigated, the remains revealed many original features, including the massive platform of what had been the pavilion with a “golden” dome, described by Ibn Battuta. Rather than steps, the pavilion was accessed by ramps; these became a feature of later Tughluq palaces. Inside the platform a series of windowless and dark chambers with thick stone walls flanking a long corridor ‒ now referred to as “dungeons” ‒ were probably safe storerooms, perhaps of the treasury.

Within the citadel, walls of some large halls of the royal apartments have also survived, sometimes incorporated into other buildings. An intriguing feature is an escape route from the citadel to the lake outside the fort: a steep stepped passage hidden in the walls and designed in a manner that once the sultan and a few of his associates entered it, the entrance could be blocked with a stone slab which would appear as part of the paved floor, and could only be opened up if it were smashed. The low narrow passage was also designed in a manner that if the enemy managed to follow the escape party, the attackers would be negotiating the steps backwards, while the defenders could fend them off from below. The route was, of course, never used, as Tughluqabad was never attacked by enemies.

The Andheri Gate is the only gate standing intact and consists of a corridor flanked by two chambers, a basic form employed for all the other gates, many of which are larger and more complex than this example.

The paper presents an updated version of the town plan, superseded later by the plans published in the book. In the town the processional street, the market squares and the market street, known as the Khass Bazaar, are explored and detailed drawings of the shops given with suggested restored appearance. A building, which was most likely a theological college (madrasa), was also surveyed, while its ruins were being demolished to salvage the stone for new houses nearby. The madrassa was one of the few structures in the town to have preserved its foundations.

The paper presents an updated version of the town plan, superseded later by the plans published in the book. In the town the processional street, the market squares and the market street, known as the Khass Bazaar, are explored and detailed drawings of the shops given with suggested restored appearance. A building, which was most likely a theological college (madrasa), was also surveyed, while its ruins were being demolished to salvage the stone for new houses nearby. The madrassa was one of the few structures in the town to have preserved its foundations.

As part of the continuous investigation of the town walls to establish the method of construction of such a massive fort and town in about two and a half years the only town gate, the Andheri Gate (“Dark Gate”) was surveyed. This is the sole gate of Tughuqabad that is still virtually intact and has retained its roof. The survey of this gate revealed the general layout of the Tughluqabad gatehouses and helped interpret ruined portions of other gates for later surveys presented in the Third Interim Report and in Tughluqabad: a paradigm of Indo-Islamic urban planning and its architectural components.

The cells known as the “Dungeons” are a series of chambers flanking a long

corridor built into the platform of the royal private apartments. They would

have been inaccessible to all except the sultan and his very few confidents

who could enter the citadel.

“Fath Jang, Ebrahim Khan (or Mirza Ebrahim)”, M. Shokoohy, EIr, vol. IX, fascicle iv, 1999, pp. 421-422.

Mirza Ibrahim Khan Fath Jang was a son of Iʿtimad-al-daula Ghiyath Beg Tihrani and brother of Nur-i Jahan, the influential wife of the Mughal emperor Jahangir (r. AH 1014-37/AD 1605-27). Together with other members of Iʿtimad-al-Daula’s family, Mirza Ibrahim entered Jahangir’s service and was first made a paymaster (bakshi) and inspector of Gujarat, responsible for reporting on the events of the region to the emperor, and within a year was given the rank of 1,000 men. After Jahangir married Nur-i Jahan in 1020/1611 Ibrahim returned to Agra. He was awarded the title of khan in AH 1023/AD 1614-15.

Ibrahim Khan first served at court as a private secretary to the emperor (bakhshigari-yi huzur), but by the end of AH 1024/AD 1616 he was made governor of Bihar and sent there to take over the region of Khukharha near Patna, an area well known for its diamond mines but hidden deep within dense and inaccessible forests and controlled by a local Hindu landlord. Ibrahim’s campaign was successful, and earned him the title of Fath Jang. He was made governor of Bengal and Orissa and held this post until AH 1033/AD 1623-24, when he was killed in battle defending the fort of Akbarnagar against the army of Shah Jahan, who had rebelled against his father. A full bibliography is included.

* “Pragmatic City versus ideal city: Tughluqabad, Perso-Islamic planning and its impact on Indian Towns” M. and N. H. Shokoohy, UDS, V, 1999, pp. 57-84, figs 5.1-5.28 (16 drawings, 12 photographs).

ISBN: 978-1-870606-07-3

ISBN: 978-1-870606-07-3

ISSN: 1358-3255

Complementing the first and second interim reports on the Survey of Tughluqabad (BSOAS, 1994 and 1999) the concept of urban planning in pre-Islamic India is explored, along with the reasons for the introduction of Perso-Islamic plans to India in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, with Tughluqabad as the earliest surviving site with such a layout. The concentric plan of traditional early mediaeval towns is analysed noting their basis on celestial diagrams with the temple-palace at the centre and the various castes living around it according to rank. Archaeological sites are noted as well as surviving examples, including Madurai in South India.

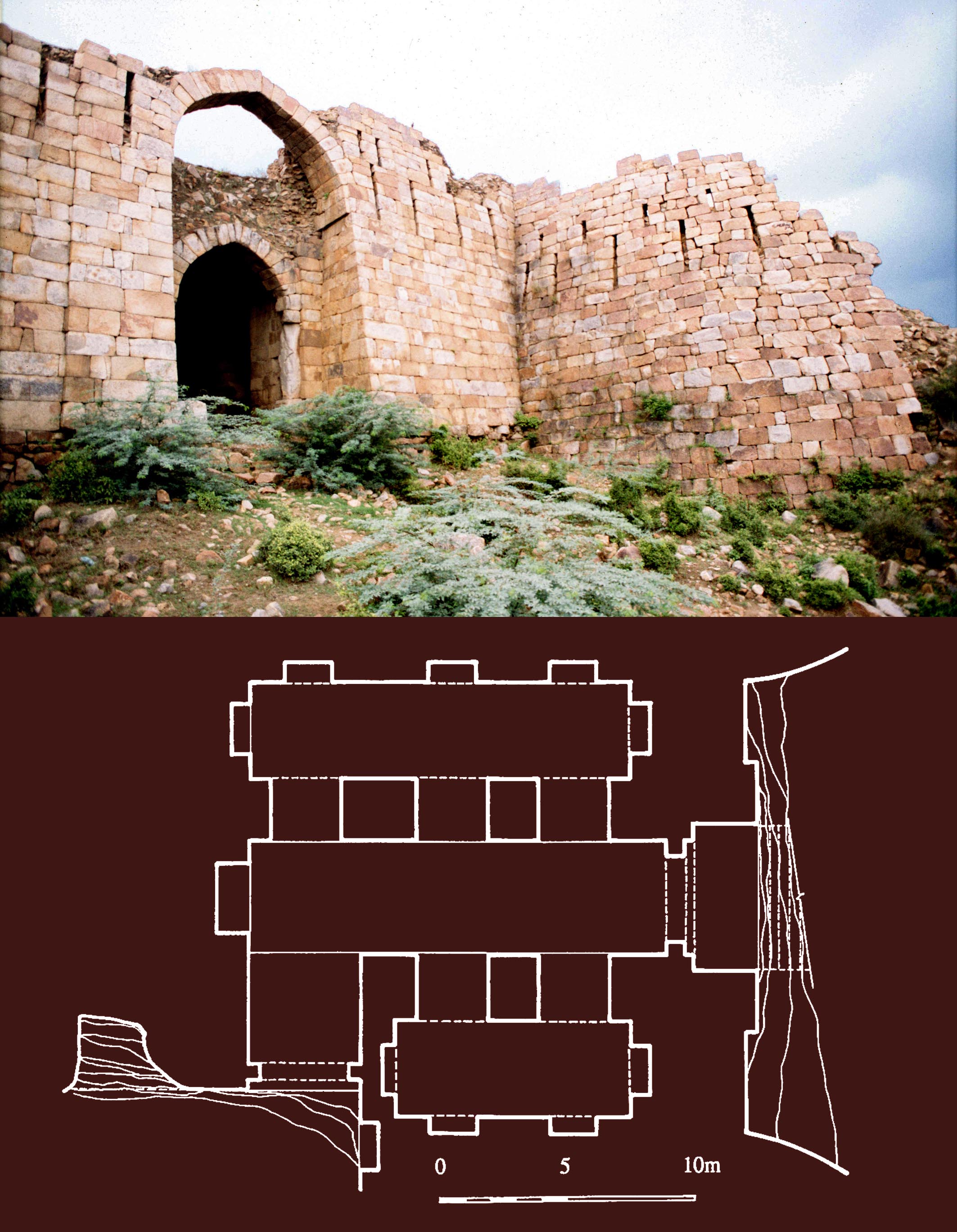

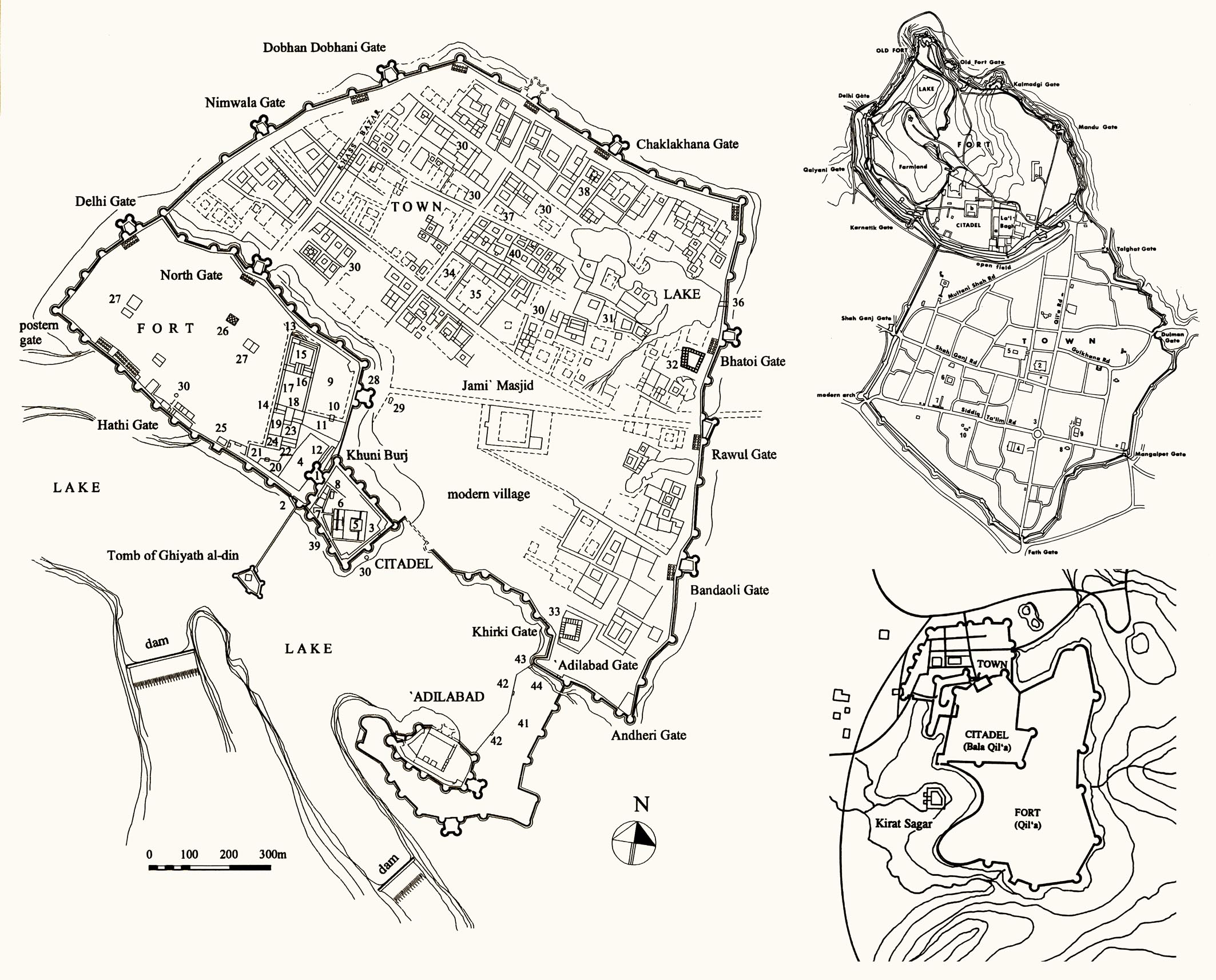

The town plan of Tughluqabad (left) comprising three main components: town, fort and citadel, was to become a prototype for almost all Indian cities from the fourteenth century to the end of Mughal period. In Bidar (top right) the town is almost the size of the citadel and the fort, while in Chanderi (bottom right) the areas taken up by the town and citadel are similar but the fort is three times larger.

A feature of Perso-Islamic towns is their royal square (maidan-i shah)

A feature of Perso-Islamic towns is their royal square (maidan-i shah)

in front of the main gate, the grand square being either within the fort

or outside it, and leading to the palace buildings. As with Tughluqabad,

the square in Bidar is located inside the fort ‒ now known as Laʽl Bagh

“the Red or Ruby Garden”.

These towns, while reflecting the social hierarchy of the population and providing for an ordered society during peacetime, were vulnerable to external attack, as an army could besiege the town walls, starve the population and take over with little conflict. Indeed some eleventh and twelfth century sultans of Khurasan (Eastern Iran) made a habit of raiding and looting the cities of north and west India using this simple strategy.

The Perso-Islamic cities were, on the other hand, designed to make sieges practically impossible, as the fort, rather than being centrally placed was set to one side of the town with the citadel again not surrounded by the fort, but occupying the optimum defendable spot to one side, and allowing the walls of the actual town to spread for several miles. To besiege such a city took a large army, not easy for a mediaeval ruler to raise and provision. The introduction of the foreign concept to India soon changed the planning of almost all Indian cities, and many of the older concentric towns added a fort to one side, altering the urban fabric and street layout.

Apart from considering the Perso-Islamic plan of Tughluqabad and many other later towns, salient features of such cities, particularly the congregational mosque and the main urban square ‒ usually known as the royal square (maidan-i shah) ‒ which provided an interface between the ruler and subject are discussed.

Apart from considering the Perso-Islamic plan of Tughluqabad and many other later towns, salient features of such cities, particularly the congregational mosque and the main urban square ‒ usually known as the royal square (maidan-i shah) ‒ which provided an interface between the ruler and subject are discussed.

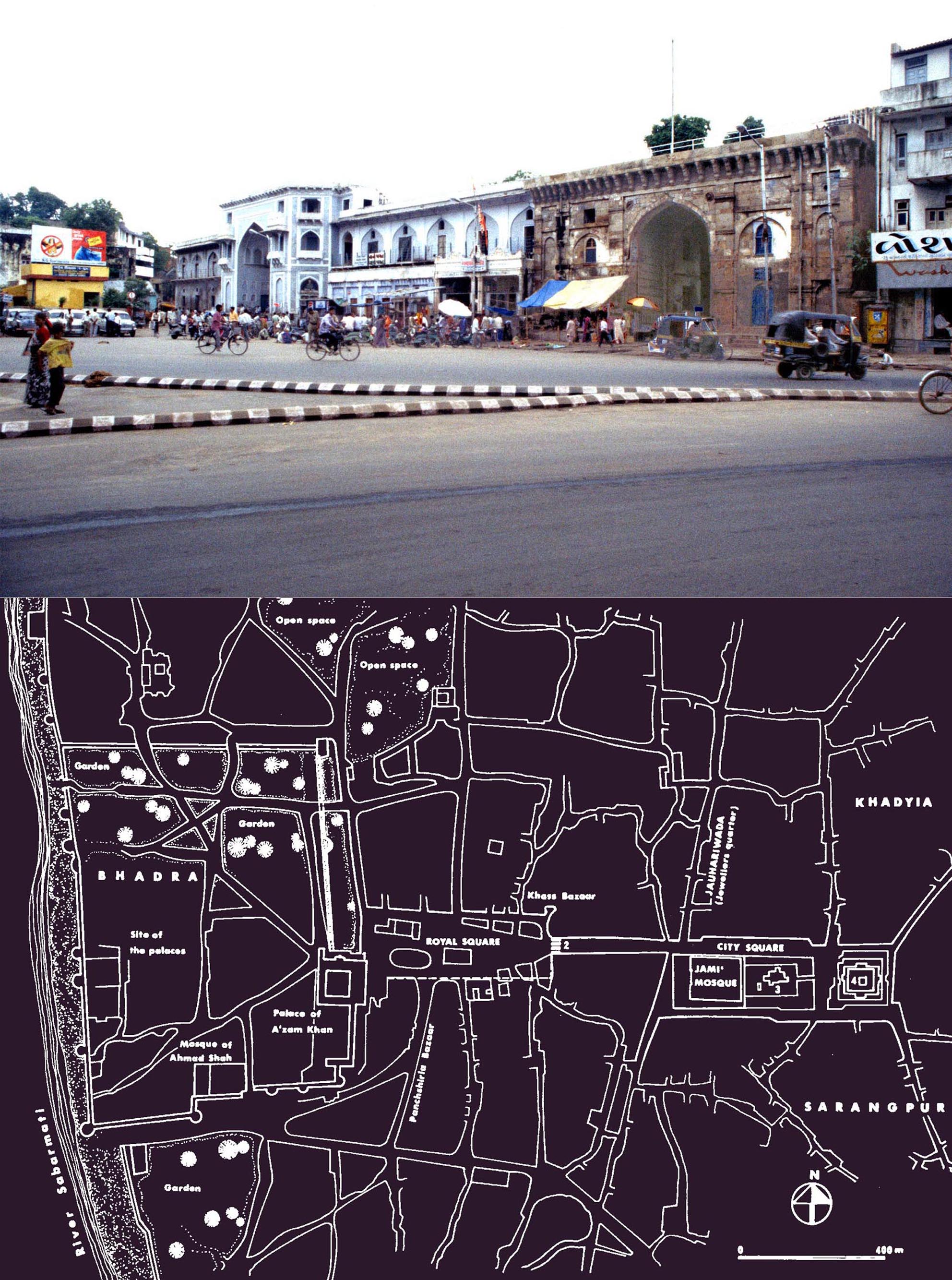

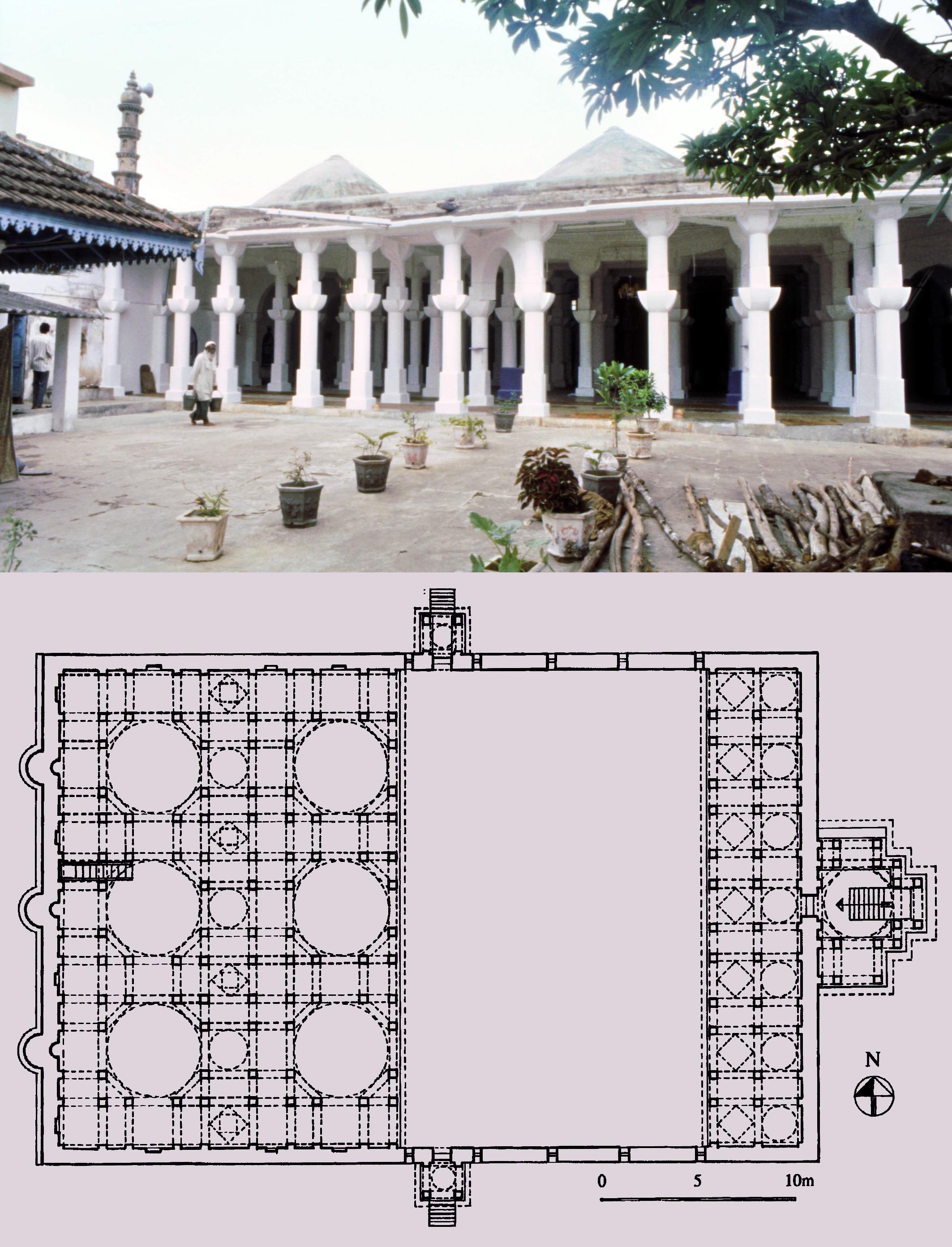

In Ahmadabad the royal square, located outside the main palace gate, opens to a processional street – integral to the design of Perso-Islamic cities – leading to the Jamiʽ (congregational) mosque. Although most of the site of the maidan-i shah of Ahmadabad is now built over, what remains forms an impressive open space.

* “The Karao Jami‘ mosque of Diu in the light of the history of the island”, M. and N. H. Shokoohy, SAS, XVI, 2000, pp. 55-72, figs 1-19 (4 architectural drawings, 15 photographs).

ISSN 0266-6030

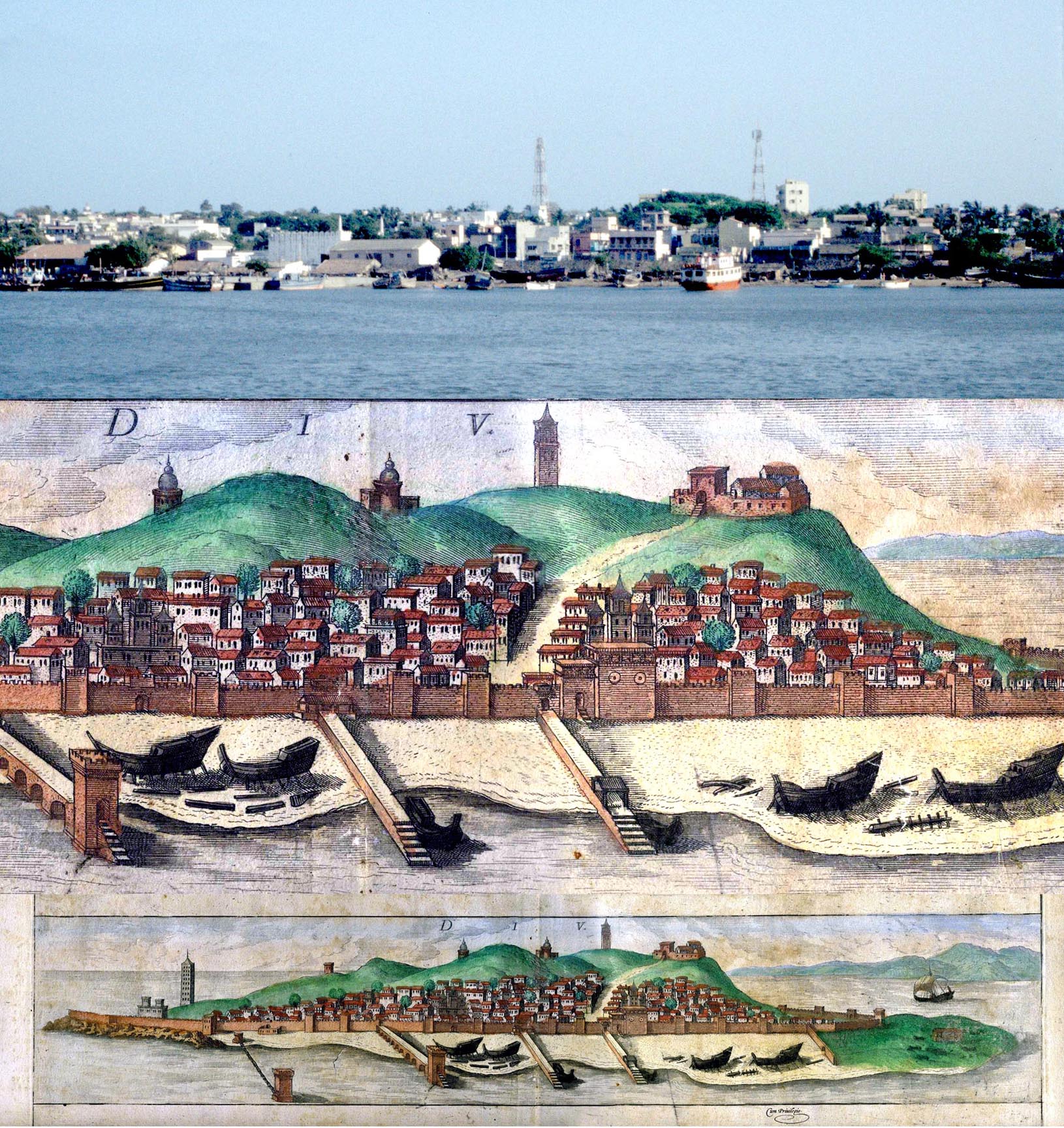

In the ex-Portuguese colony of Diu there stands an impressive old mosque. Its interest is more than architectural as its very survival under the Portuguese may throw light on some aspects of the history of the Portuguese in India and their relationship with the Muslims of the region, particularly with regard to the infamous practice of burning the mosques of many South Indian ports.

Ludovico di Varthema, who visited Diu in 1503 or 1504 notes: “This city is subject to the Sultan of Combeia (Gujarat), and the captain of this Diuo is one named Menacheaz (Malik Ayaz). Four hundred Turkish merchants reside here constantly. This city is surrounded by walls and contains much artillery within it", and Barbosa in c. 1515, gives vivid descriptions of Diu, its administration and trade before it fell into the hands of the Portuguese. Varthema records: “The king keeps a Moorish governor in this place called Melquiaz; an old man, and a very good gentleman, discreet, industrious, and of great information. He always keeps with him many men-at-arms, to whom he pays very good appointments.”

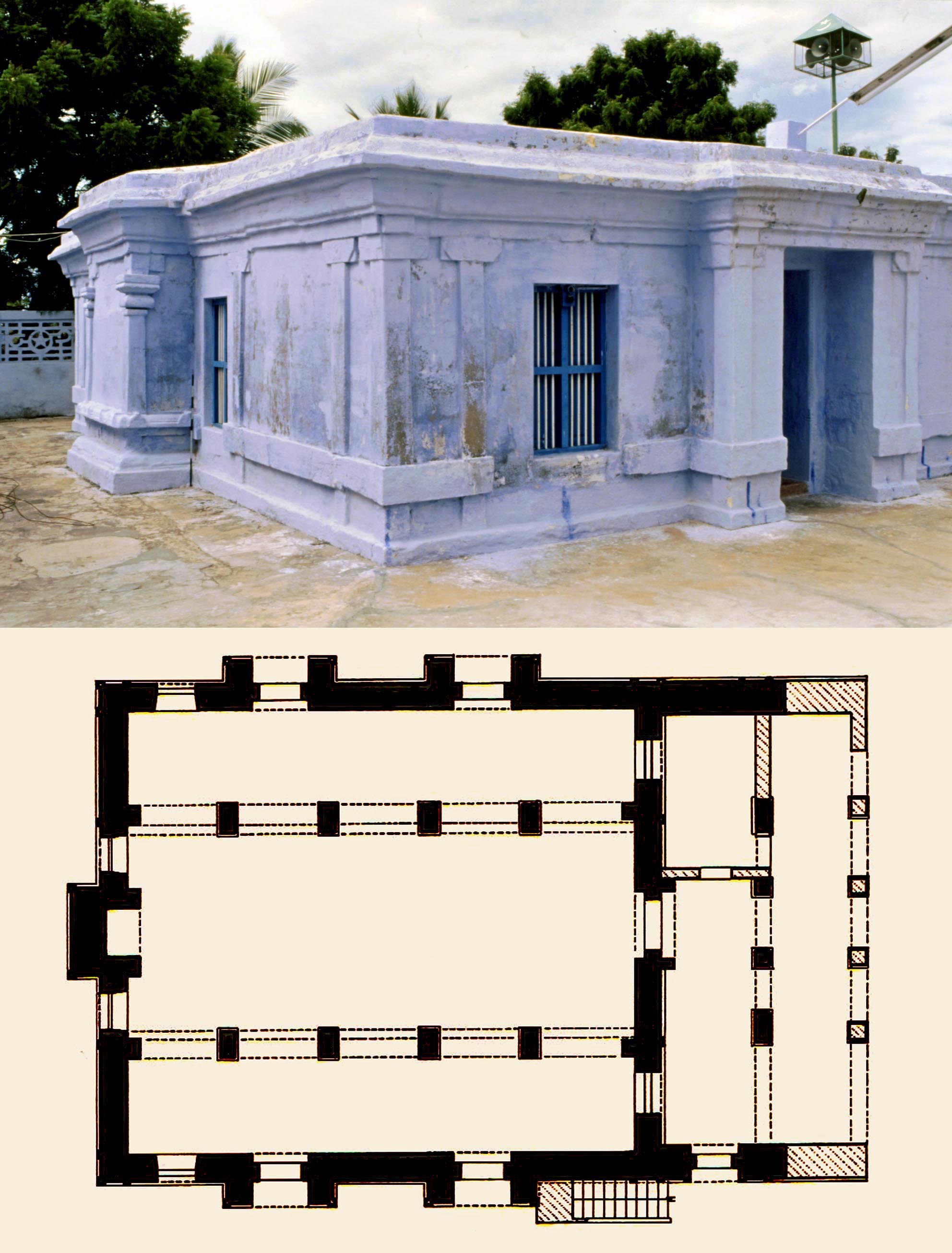

In the turbulent relationship between the Gujarat sultanate and the Portuguese, the former was in control of the town and the latter their fort there. Later, during the Mughal period the Portuguese, while taking over the town, chose to have a non-confrontational policy with the mighty empire and, unlike other Portuguese territories in India, Diu sustained its Muslim population. The Karao mosque, however, pre-dates the Portuguese and even the sultanate of Gujarat. Its plan and use of temple spoil indicate that it was built at the time of Delhi’s conquest of Gujarat at the beginning of the fourteenth century. Incorporating a variation of the local style of the late thirteenth to fourteenth century mosques of Gujarat, it differs from those of the fifteenth and sixteenth century, as in this building the colonnade opens to the courtyard without having a screen wall with one or more large arched openings set in front of the prayer hall, typical of later Gujarati mosques. The main entrance of the Karao Jami‘, with its domed canopy and an entrance and stairs below, seems to be a haphazard re-assembly of the entrance to a Jain temple. The Diu mosque is indeed the oldest monument on the island and has remained in everyday use for over seven hundred years.

In the turbulent relationship between the Gujarat sultanate and the Portuguese, the former was in control of the town and the latter their fort there. Later, during the Mughal period the Portuguese, while taking over the town, chose to have a non-confrontational policy with the mighty empire and, unlike other Portuguese territories in India, Diu sustained its Muslim population. The Karao mosque, however, pre-dates the Portuguese and even the sultanate of Gujarat. Its plan and use of temple spoil indicate that it was built at the time of Delhi’s conquest of Gujarat at the beginning of the fourteenth century. Incorporating a variation of the local style of the late thirteenth to fourteenth century mosques of Gujarat, it differs from those of the fifteenth and sixteenth century, as in this building the colonnade opens to the courtyard without having a screen wall with one or more large arched openings set in front of the prayer hall, typical of later Gujarati mosques. The main entrance of the Karao Jami‘, with its domed canopy and an entrance and stairs below, seems to be a haphazard re-assembly of the entrance to a Jain temple. The Diu mosque is indeed the oldest monument on the island and has remained in everyday use for over seven hundred years.

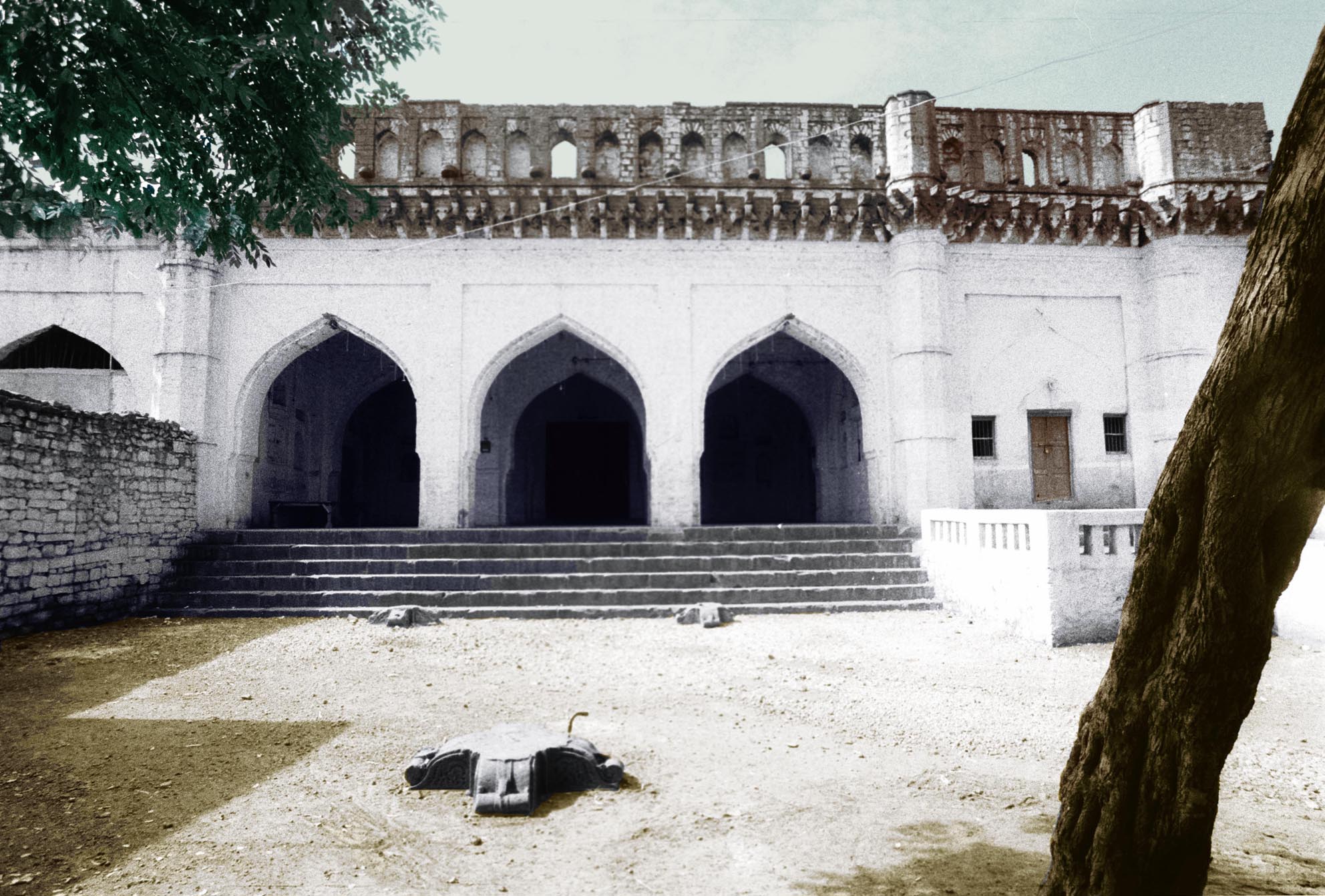

The spacious Karao Jamiʽ mosque, one of the few surviving

first-generation mosques of the sultanate of Delhi in Gujarat,

built at the time of, or soon after, the Delhi take-over of the

region in AH 698 (AD 1298-9).

“Giat Beg (Ghiat-al-din Mohammad Tehrani) E‘temad-al-dawla”, M. Shokoohy, EIr, vol. X, fascicle vi, 2001, pp. 594-595.

I`timad al-daula was the grand vizier of the Mughal emperor Jahangir and father of the emperor's wife, Nur-i Jahan. He was the younger of the two sons of Khwaja Muhammad Sharif Hijri (d. AH 984/AD 1576-7), Minister of Yazd and later Isfahan in the Persian court of the Safavid Shah Tahmasb. Muhammad came from a learned family of Tehran, and one of his brothers was Mirza Ahmad Tehrani, a close companion of Shah Tahmasb. Ahmad's son Mirza Amin Razi is renowned for his book Haft Iqlim, and Ghiyath Beg's brother was the poet Mohammad Tahir, known as Wasli.

I`timad al-daula was the grand vizier of the Mughal emperor Jahangir and father of the emperor's wife, Nur-i Jahan. He was the younger of the two sons of Khwaja Muhammad Sharif Hijri (d. AH 984/AD 1576-7), Minister of Yazd and later Isfahan in the Persian court of the Safavid Shah Tahmasb. Muhammad came from a learned family of Tehran, and one of his brothers was Mirza Ahmad Tehrani, a close companion of Shah Tahmasb. Ahmad's son Mirza Amin Razi is renowned for his book Haft Iqlim, and Ghiyath Beg's brother was the poet Mohammad Tahir, known as Wasli.

After the death of his father Ghiyath Beg lost favour in the court of Isfahan, and together with his family escaped to India entering the court of the Emperor Akbar, and at the time of Jahangir was appointed vizier of half of the empire, with the title of I`timad al-daula. While one of his sons and his son-in-law (the former husband of Nur-i Jahan) joined the camp of Jahangir’s enemies, Ghiyath Beg retained his status in court and gradually became extremely powerful after Jahangir married Nur-i Jahan.

Ghiyath Beg was known for his refined manners, his knowledge of literature, and his skill in calligraphy. In the words of Ma'athir al-Umara: "He was always conscious of the future, self-composed, and did not harbour grudges even against his enemies. He was not at all oppressive, and in his household there were no fetters, chains and whips, nor words of abuse." His tomb in Agra is one of the finest monuments of the Mughal period and a forerunner of the Taj Mahal. A full bibliography is included.

The tomb of Iʽtimad al-daula, built under the supervision of his daughter Nur-i Jahan. Although a small building – fit for a highly respected minister – the workmanship of the finely carved marble facades, inlaid with coloured stone, is equal to that of Taj Mahal.

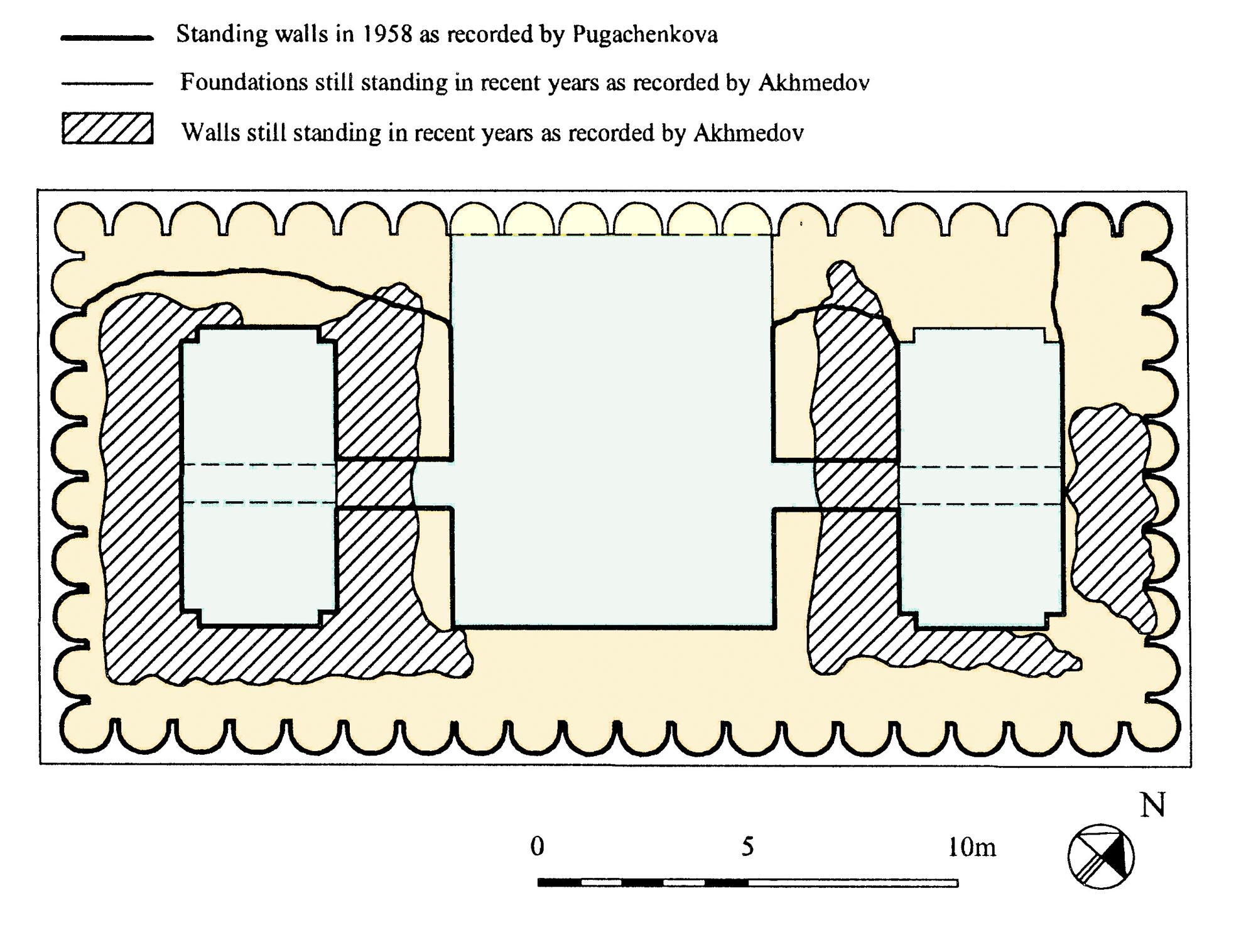

* “The Zoroastrian fire temple in the ex-Portuguese colony of Diu, India”, M. Shokoohy, JRAS, Series 3, vol. XIII, i, 2003, pp. 1-20, figs. 1-17 (6 drawings, 11 photographs).

ISSN 1356-1863

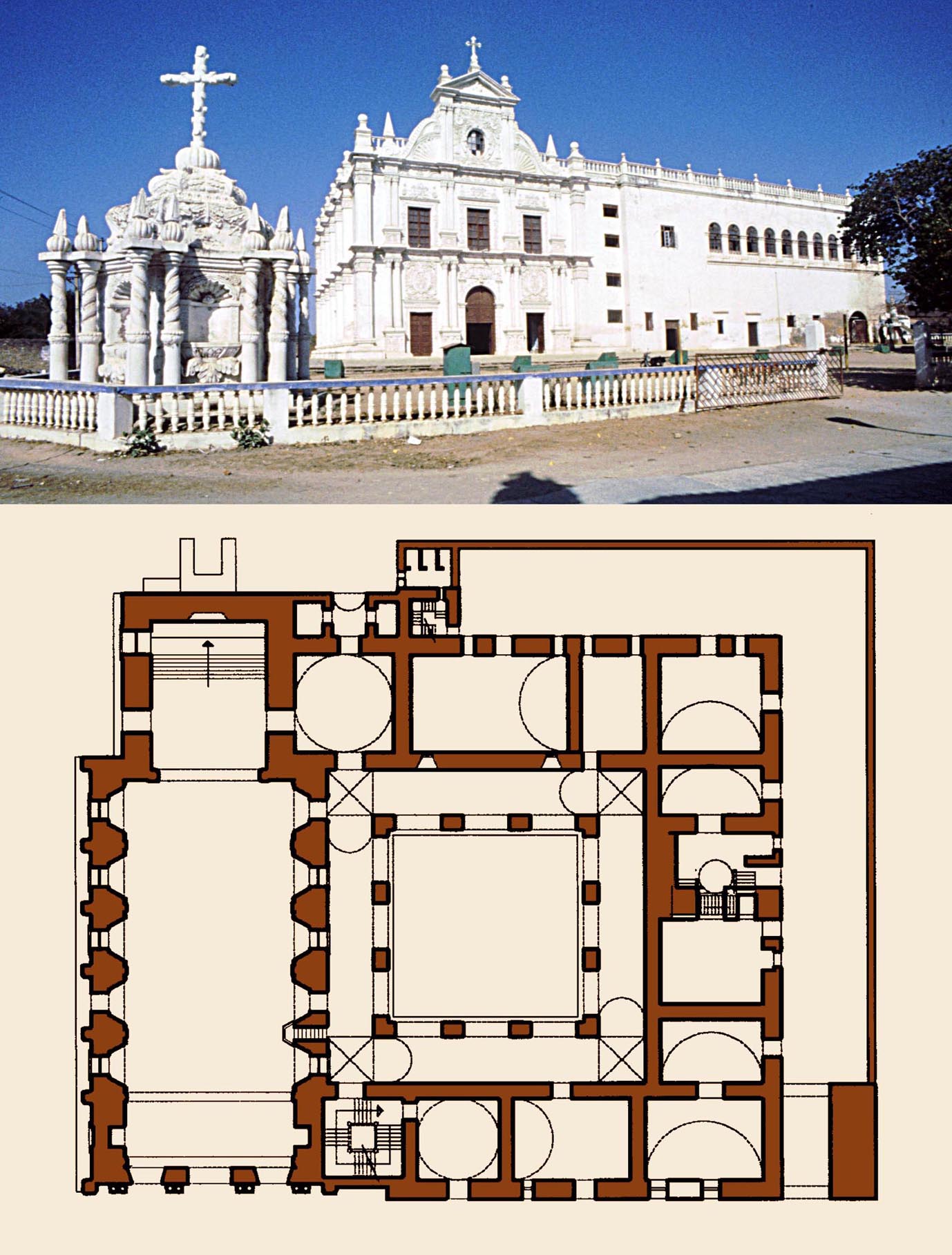

Although the last Zoroastrian families left the island in about 1950, the survival of the fabric of the fire temple of Diu for over half a century without much alteration is mainly a result of decisions made by the last members of the community. The sacred element in a fire temple, the fire itself, should be kept alive at all times and when a community leaves an area the fire is taken away. The building in itself has no sanctity and can be left abandoned or used for other purposes. This has been the fate of many of the grand fire temples in Iran over their long history and particularly after the dominance of Islam. The community in Diu, however, preferred the building to be re-used in an appropriate way for the benefit of all people of the island. It was donated to the Church and a group of nuns from Goa were sent to set up a convent there. The building, now St. Anne’s Convent, is a centre for service to the island’s community and also has a successful infants’ school accepting children of all castes and creeds.

Although the last Zoroastrian families left the island in about 1950, the survival of the fabric of the fire temple of Diu for over half a century without much alteration is mainly a result of decisions made by the last members of the community. The sacred element in a fire temple, the fire itself, should be kept alive at all times and when a community leaves an area the fire is taken away. The building in itself has no sanctity and can be left abandoned or used for other purposes. This has been the fate of many of the grand fire temples in Iran over their long history and particularly after the dominance of Islam. The community in Diu, however, preferred the building to be re-used in an appropriate way for the benefit of all people of the island. It was donated to the Church and a group of nuns from Goa were sent to set up a convent there. The building, now St. Anne’s Convent, is a centre for service to the island’s community and also has a successful infants’ school accepting children of all castes and creeds.

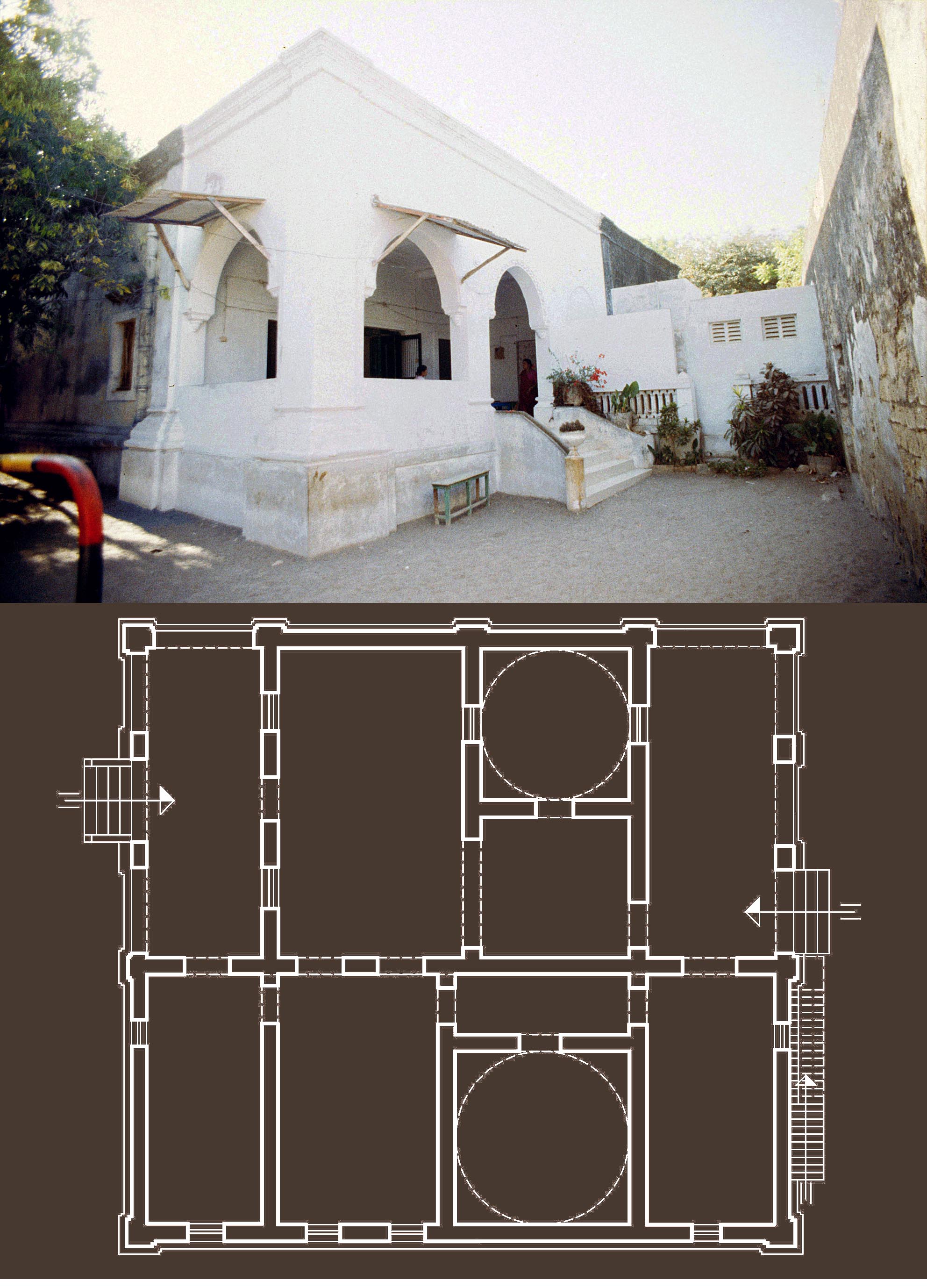

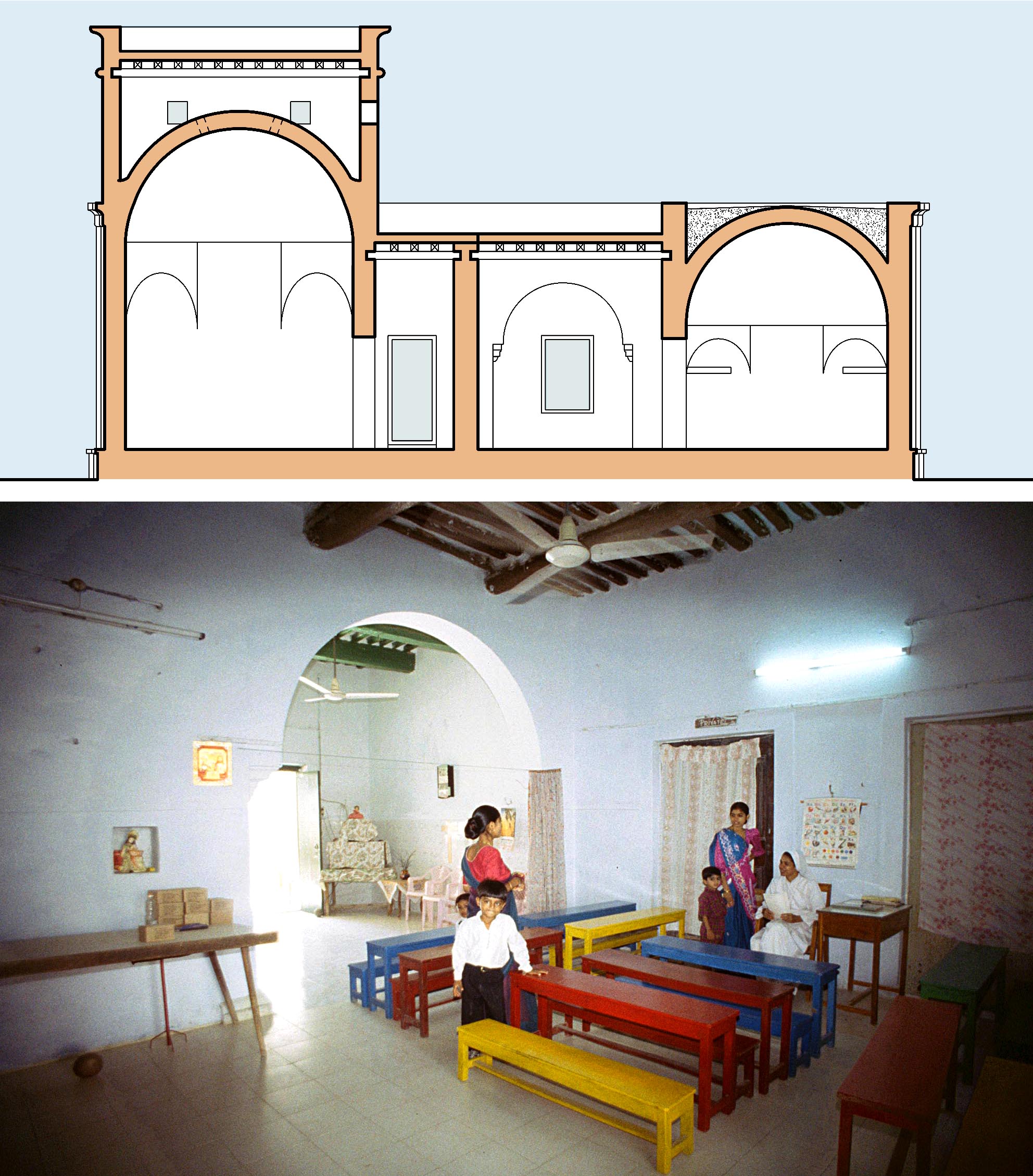

In general form and in its structural elements the building is a product of the Portuguese colonial methods employed in Diu, but, as with most modern – and historic – fire temples the building has a simple plan, consisting of two interconnected halls each with an arched portico and two domed chambers. The northern part of the building was for the use of the congregation with the small domed chamber in a focal position housing the fire altar where the sacred fire was brought for public worship. The fire was, however, kept alive permanently in the larger chamber with its adjoining rooms closed to the public, being used by the priests for keeping liturgical objects and fire-wood.

Plan and exterior view of the fire temple of Diu. A straight

wall separates the two porticos, the halls and the small

domed chamber open to worshipers from the series of

chambers which could be accessed only by the priests,

including a large domed windowless chamber.

The good state of preservation of the structure provides a rare opportunity to gain an insight into what are perceived as recent architectural traditions for Indian fire temples. The sacred nature of these buildings often forbade immediate access for the purpose of survey and photography. As a result there has been little study on the architecture of functioning fire temples and much needs to be done before a cohesive picture of the design development of modern temples can emerge. The paper also discusses in depth the liturgical requirements which tie these building to their historical predecessors, now mostly in ruins, in Iran.

The good state of preservation of the structure provides a rare opportunity to gain an insight into what are perceived as recent architectural traditions for Indian fire temples. The sacred nature of these buildings often forbade immediate access for the purpose of survey and photography. As a result there has been little study on the architecture of functioning fire temples and much needs to be done before a cohesive picture of the design development of modern temples can emerge. The paper also discusses in depth the liturgical requirements which tie these building to their historical predecessors, now mostly in ruins, in Iran.

Above, a section through the two domed chambers and one of the assembly halls and below, a view of the same hall now used as a classroom.

* “Tughluqabad, third interim report: gates, silos, waterworks and other features”, M. and N. H. Shokoohy, BSOAS, vol. LXVI, i, 2003, pp. 14-55, figs 1-18, pls 1-27.

ISSN: 0041-977X

EISSN: 1474-0699

The Tughluqabad gates are similar in concept, but each is unique in layout as they had to be inserted into the gaps left between the fortification walls, which were built first. The Rawul gate, with its adjacent silos, is unusual in having a triangular, rather than trapezoid outer court and on the north an additional chamber (at left in photograph) to fill the long gap left between the flanking walls.

The last interim report focuses on the infrastructure of Tughluqabad as well as its urban form, and how the town walls and the town itself could be constructed in only two and a half years. In the 6th season of fieldwork in 1999, the remains of two of the gates in the fort and some of those in the town were recorded, as well as the silos attached to some gates. The residential areas of the north of the town were further investigated including a sizeable mansion. Within the fort the remains of a reservoir, a main supply of water, was also detailed. Photographs and measured drawings of all these features are given together with an updated town plan.

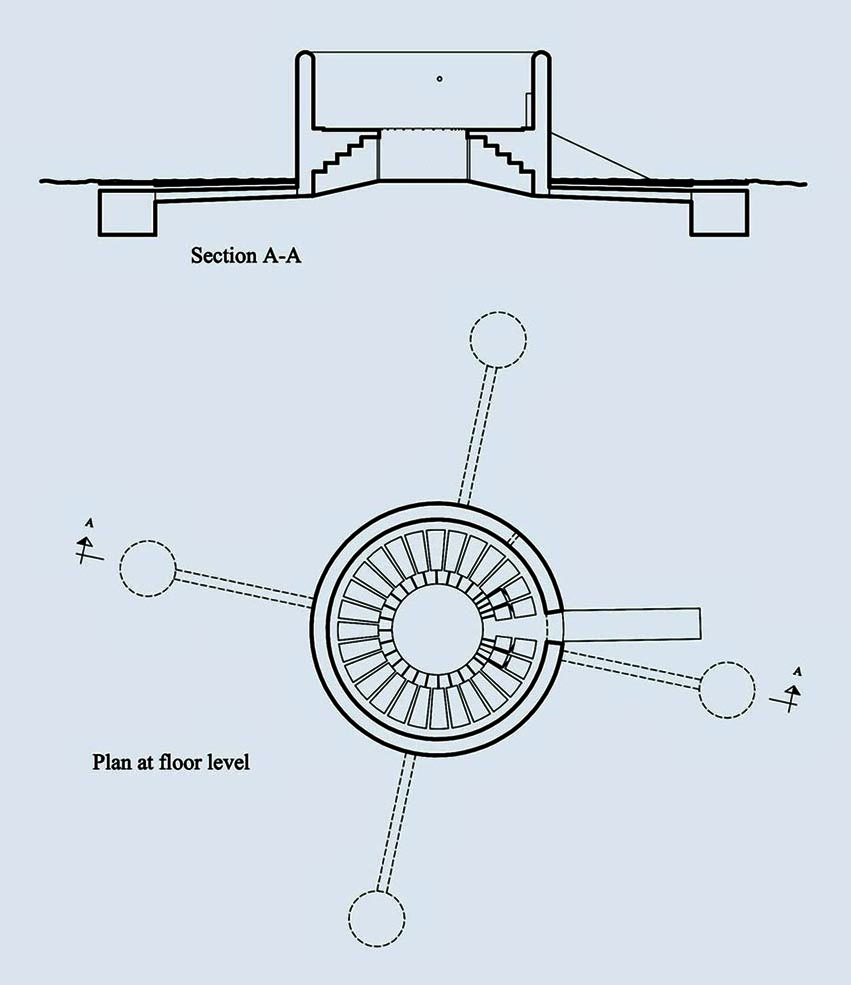

One of the prominent features in Tughluqabad is the extensive lake created to the south of the town, as part of the original design, not only to provide water but also to create a micro-climate with increased humidity which would have moderated the temperature during the dry season. The water was controlled by a single ingenious sluice gate ‒ sophisticated in design, but simple to operate. A fresh survey gives details of how it worked; drawings include a three-dimensional reconstruction showing how the water of a lake almost as vast as the town itself could be controlled by a single person ‒ a fresh design concept, which has not been seen elsewhere in India.

One of the prominent features in Tughluqabad is the extensive lake created to the south of the town, as part of the original design, not only to provide water but also to create a micro-climate with increased humidity which would have moderated the temperature during the dry season. The water was controlled by a single ingenious sluice gate ‒ sophisticated in design, but simple to operate. A fresh survey gives details of how it worked; drawings include a three-dimensional reconstruction showing how the water of a lake almost as vast as the town itself could be controlled by a single person ‒ a fresh design concept, which has not been seen elsewhere in India.

In 1999 the Tomb of Ghiyath al-din Tughluq and the citadel of ‘Adilabad were also surveyed, and are published in Tughluqabad, a paradigm for Indo-Islamic urban planning and its architectural components.

The Rawul Gate, like most of the gates, incorporates a structure

with ten silos, circular in plan and roofed with flat domes. The grain

stores were filled from small apertures in the roof, but access could

only be achieved by order of the sultan to dismantle the dome or

part of it, in case of famine.

“Hasan Gangu (Kangu or Kanku): Ala al-din Hasan Bahman Shah”, M. Shokoohy, EIr, vol. XII, fascicle i, 2003, pp. 33-34.

Hasan Gangu (Kangu or Kanku) was a Khurasani adventurer at the court of Muhammad ibn Tughluq at Delhi, and after rebelling against his master declared himself Sultan of the Deccan with the title ʿAla al-din Bahman Shah (r. AD 1347-57). He claimed descent from the Sasanian Bahram Gur and founded the Bahmanid dynasty, which lasted until AD 1527. He was the son of Keykawus Muhammad b. ʿAli b. Hasan; and his uncle Malik Huzhabr-al-din Zafar Khan was a noble at the court of Sultan ʿAla al-Din Khalji and the governor of Multan and the Punjab.

Hasan is said to have been originally from Ghazni, entering the services of Sultan Muhammad ibn Tughluq together with his brothers who were all given small fiefdoms in the Deccan. Hasan was eventually made Governor of the district of Gulbarga with the honorary title of Zafar Khan. When the brothers revolted they were at first defeated and the two of them put to death, but Zafar Khan joined the other rebellious nobles and on 24 Rabiʿ II 748/3 August 1347, he was proclaimed Sultan ʽAla al-din Bahman Shah. Muhammad ibn Tughluq, immersed in troubles, never returned to the Deccan and died soon afterwards.

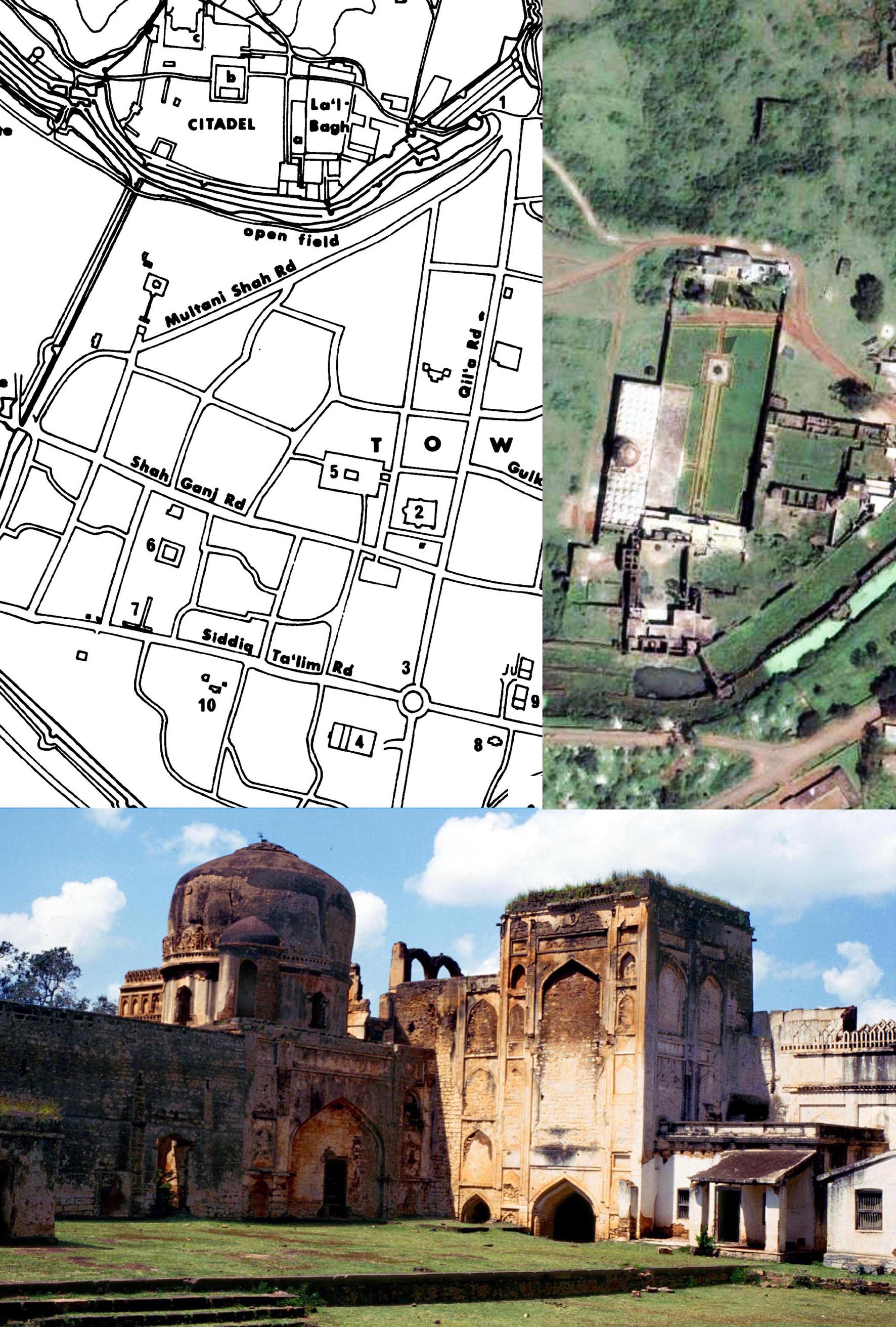

The fortifications of Gulbarga, originally pre-dating

The fortifications of Gulbarga, originally pre-dating

the Bahmani dynasty, but rebuilt and re-enforced

during their reign.

ʿAlaʾ-al-Din made Gulbarga the capital of the Deccan and a flourishing canter of Persian culture. The capital was later moved by Shihab-al-din Ahmad I (r. AH 825-39/AD 1422-36) to Bidar. The tombs of ʿAlâʾ-al-Din and some of his successors, built as domed chambers, are still standing along an avenue in a necropolis just outside the perimeter of the old town walls. The concept of a royal necropolis is unusual in India, as is the curious device of a pair of outspread wings cradling the crescent moon within which is a disc or rosette and which, similar to the Sasanian royal emblem, crowns the arches of these tombs (see “Sasanian royal emblems and their re-emergence in the fourteenth-century Deccan”, in Muqarnas, XI, 1994). They indicate that ʿAlâʾ-al-Din and his immediate successors had a close knowledge of the pre-Islamic culture and architecture of Persia. They also invented court protocols that alluded to those of the kings in the Shahnama and the Abbasid caliphs. The symbols of royalty included a black parasol and royal curtain, while the throne of Muhammad b. ʿAla al-din, known as the takht-e firuza, was treated like the royal standard of the Sasanians (dirafsh-i Kawiyan). It was studded with jewels added to it by each sultan, to the extent that in later dates its original turquoise enamel over gold casing on ebony could no longer be seen. The various rumours about ʽAla al-din Hasan’s origins may have been partly responsible for the Bahmani sultans’ insistence on publicizing their claim to Sasanian lineage by every means at their disposal. The paper includes a full bibliography including works concerned with the obscure origins of the sultan.

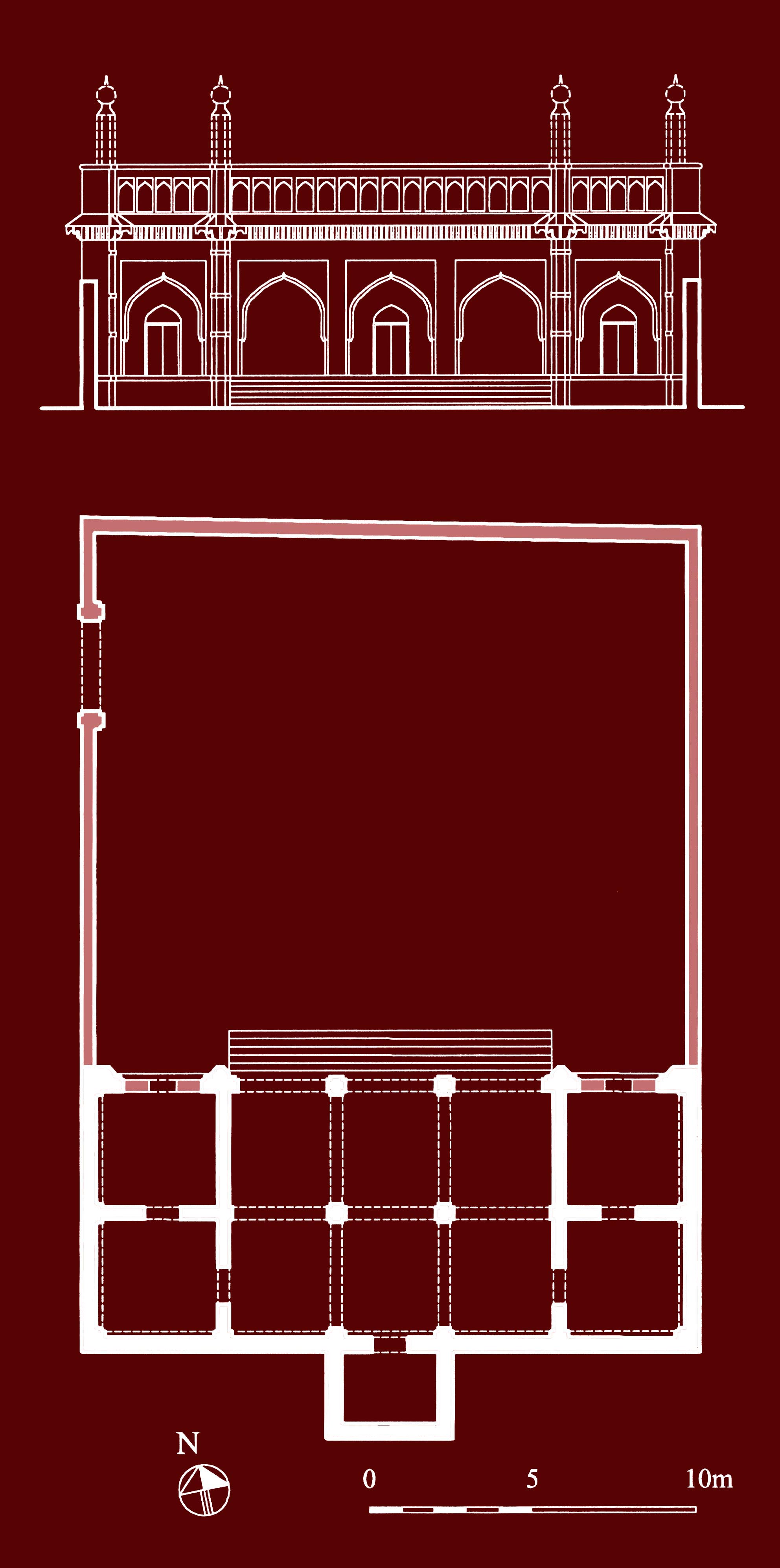

* “Domestic dwellings in Muslim India: mediaeval house plans”, M. and N. H. Shokoohy, BAI, vol. XIV, (2000 nominal, published 2003), pp. 89-110, figs 1-21 (10 architectural drawings, 11 photographs).

ISSN: 0890-4464