Darzin, now a village in the arid region of south-east Iran by the main road from Kirman to Bam, was originally a substantial agricultural town, recorded in the Muslim geographies including the Hudud al- `Alam (AH 372/AD 982-3) and those of Ibn Hauqal (AH 378/AD 998-9) and Yaqut (d. AH 626/AD 1228-9). Vaziri, the nineteenth-century geographer of Kirman, quotes a description of Darzin given in a twelfth century history, `Iqd al `ula:

“On every side that the line of vision fell there were chequer-board cultivation plots, flowing water-courses, verdant landscape and agriculture. The man of Fars swore that whilst they say Fars is half the world and famous for its freshness and the high standard of its crops, he had seen no district of that region comparable with this land (of Darzin) for its refreshing gardens, agreeable ponds and quality of products”

“On every side that the line of vision fell there were chequer-board cultivation plots, flowing water-courses, verdant landscape and agriculture. The man of Fars swore that whilst they say Fars is half the world and famous for its freshness and the high standard of its crops, he had seen no district of that region comparable with this land (of Darzin) for its refreshing gardens, agreeable ponds and quality of products”

and then adds:

“For a long time Darzin was in ruins, now ... a stream from the mountain-range of Abriq has been brought to that region, which today is again inhabited”.

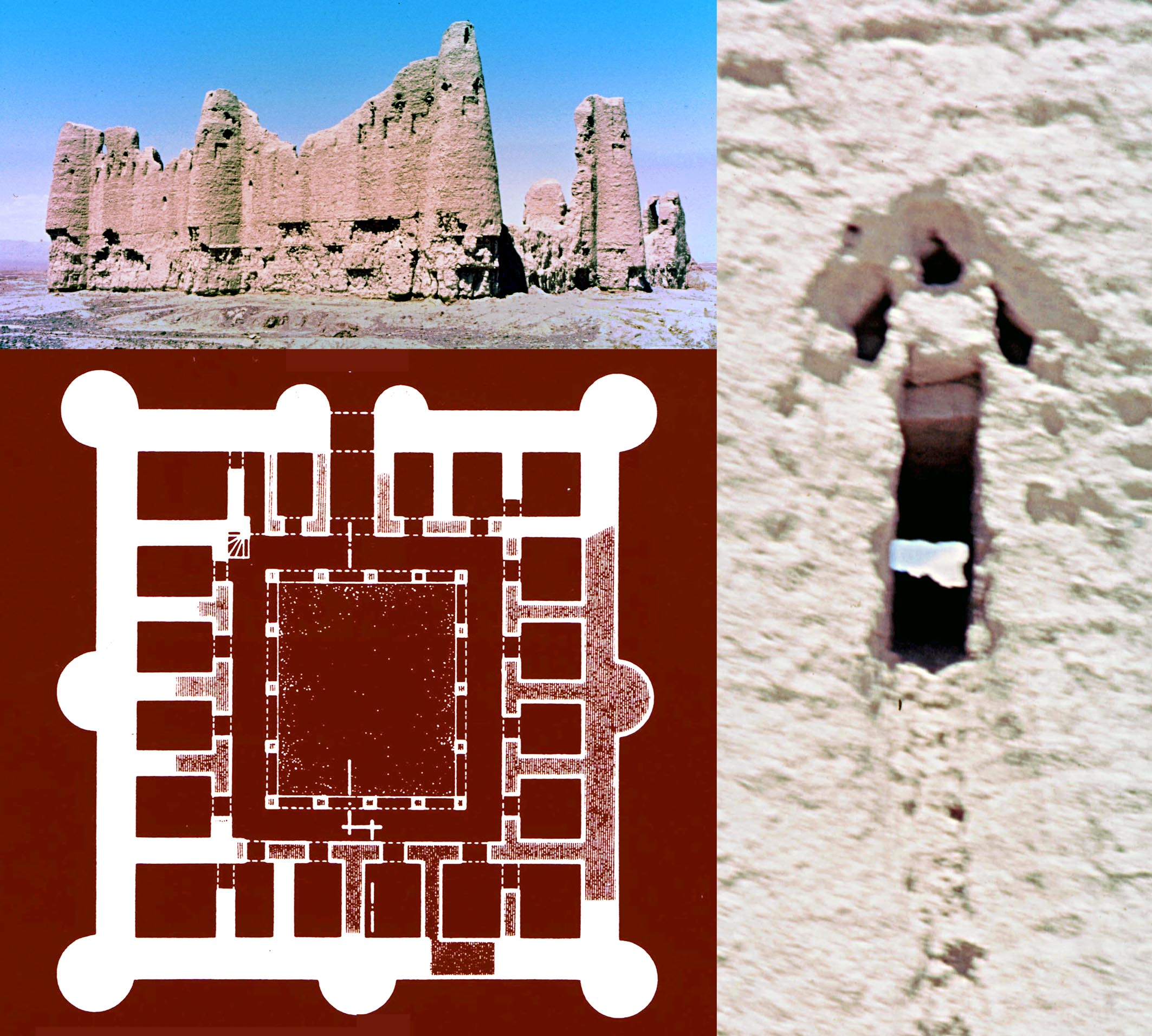

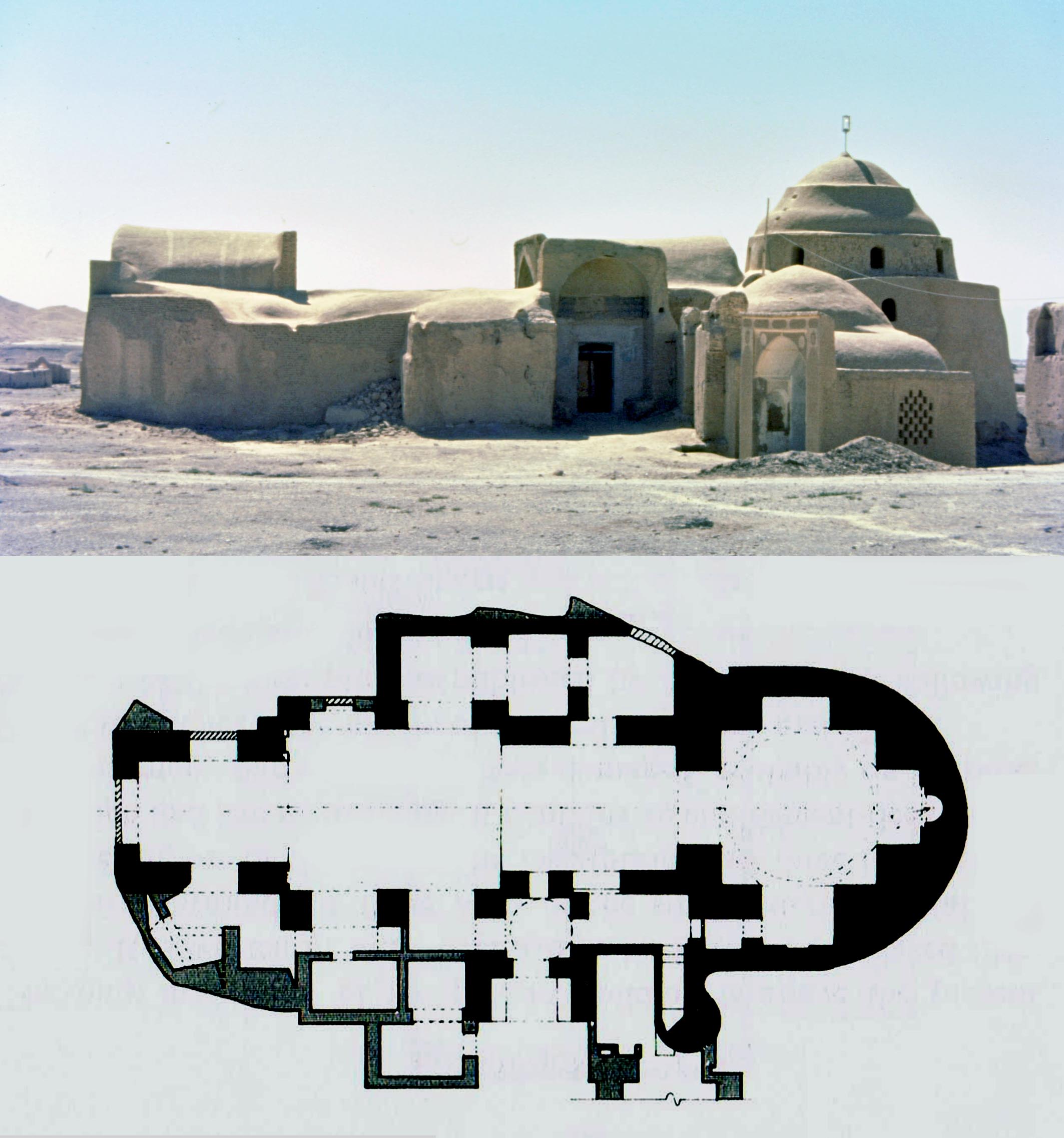

Darzin, a view of Fort 1 and plan of Fort 2 (standing remains are shaded) as well as an example of an arrow-slit, many of which are found in all three forts. The arrow-slits are characteristic of early Caliphate buildings including the enclosures at al-Ukhaidir and Qasr al-Kharrana.

East of the present village stand the remains of a number of mud-brick buildings, including three square forts, surrounded by a substantial spread of pottery containing a fair proportion of slip-painted ware, confirming habitation since at least the tenth century. Survey drawings of the two forts which have survived better are given. The plans of all three forts, together with other surviving architectural features, including the form of the arrow-slits and the parabolic – or slightly pointed – vaults, along with the large size of the bricks (27×27×7 cm) all conform with the architecture of the very early Caliphate period and are indeed similar to those of even earlier pre-Islamic – Sasanian – buildings. The forts, therefore, appear to be among the oldest surviving Islamic buildings in Iran, representing the transformation of Sasanian to early Islamic architecture.

“Archaeological notes on Lashkari Bazar, Afghanistan”, M. Shokoohy and Géza Fehérvári, Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes, LXXII, 1980, pp. 83-95.

The study of the fort of Bust and the unpublished monuments between Bust and Lashkargah (Lashkari Bazar) was a part of Mehrdad Shokoohy’s research for his doctoral thesis. After the completion of the thesis in 1978, several reports concerning these sites came out and this part of the thesis is unpublished. The thesis includes a fresh reading of the inscription of an arch in the fort suggesting its date as AH 400/AD 1009-10, a survey of a previously unstudied elaborate well with stairs to cool underground chambers in the fort, and a full survey of an early octagonal tomb chamber, known as Marqad-i Shahzada Sarbaz, which was later published by a colleague.

This paper is a review article of Daniel Schlumberger’s Lashkari Bazar, une résidence royale ghaznavide et ghoride, Mémoires de la Délegation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan, Tome XVIII, Paris, 1978. This exhaustive work in three volumes presents the final report of Schlumberger and his team’s excavations of the royal palaces at Lashkargah (organised and published after Schlumberger’s death).

The paper highlights the importance of this extremely valuable contribution to Afghan studies, but also points to some other aspects of the site, particularly the fort and the well, which were outside of the scope of Schlumberger’s excavations. For example, Farrukhi, the Ghaznavid court poet, extols not only the palace in the plain of Lashkargah (excavated by Schlumberger) but speaks of another palace, of which little has survived, in the citadel, but which still awaits excavation should conditions in the country make this possible.

The paper highlights the importance of this extremely valuable contribution to Afghan studies, but also points to some other aspects of the site, particularly the fort and the well, which were outside of the scope of Schlumberger’s excavations. For example, Farrukhi, the Ghaznavid court poet, extols not only the palace in the plain of Lashkargah (excavated by Schlumberger) but speaks of another palace, of which little has survived, in the citadel, but which still awaits excavation should conditions in the country make this possible.

Ruins of some of the many grand mansions associated with the Gaznavid courtiers and army commanders between Bust and the palace at Lashkargah. Located near the River Hirmand (Helmand) the whole area would have been irrigated and lush with green fields, orchards and gardens. With the exception of the palace complex at Lashkargah and its immediate neighbouring structures, none of these mansions have so far been properly investigated.

“A signed bronze vessel with human figures”, M. Shokoohy and Géza Fehérvári, Essays in Islamic Art and Architecture in Honour of Katharina Otto-Dorn, (Islamic Art and Architecture 1, Undena Publications) Malibu, Ca., 1981, pp. 37-41, figs 1-9.

In the Keir collection there is a curious lobed vessel engraved and inlaid with personifications of the signs of Zodiac. The object is not symmetrical and does not have the smooth surface prerequisite for a cup, and as the images are upright, they would read upside-down as the lid or cap of another object. It seems to be part of a more complex piece with an element attached below and perhaps another above.

The vessel has thirteen highly ornamented segments, twelve of which are alternately decorated with six arabesques and six human figures, which could be interpreted as representing planets: first the moon; second with a pickaxe, Saturn; third with a sword, Mars; fourth playing a lute, Venus; fifth holding a bottle, Jupiter and sixth with a book, Mercury. The missing image is the sun, which seems to have been the object once fitted inside the vessel.

The thirteenth segment bear the artist’s signature and reads mimma `amal Yusuf ibn Muhammad (this was made by Yusuf ibn Muhammad). The name of this bronze-worker has not yet been seen elsewhere, yet dedicating a whole segment to his name indicates that he was well known and his signature would have added prestige to the article.

The thirteenth segment bear the artist’s signature and reads mimma `amal Yusuf ibn Muhammad (this was made by Yusuf ibn Muhammad). The name of this bronze-worker has not yet been seen elsewhere, yet dedicating a whole segment to his name indicates that he was well known and his signature would have added prestige to the article.

The vessel is most likely to have been made in thirteenth century Iran, probably in the region of Azerbaijan, as it was in this area that objects were made of bronze, in contrast with those known as the products of Ayyubid Syria or the so called “Mosul school” which were made of brass.

The craftsman’s signature prominent on the bronze piece. Although not

mentioned in the paper, the object may well have been the cup of a

Byzantine chalice; many chalices with similar lobed cups have survived.

Byzantine patrons often employed Muslim craftsmen, particularly metal-

workers, whose skills were widely appreciated at the time.

* “The monuments at the Kuhandiz of Herat, Afghanistan”, M. Shokoohy, JRAS, I, 1983, pp. 5-31, figs 1-9, pls 1-8.

* “The monuments at the Kuhandiz of Herat, Afghanistan”, M. Shokoohy, JRAS, I, 1983, pp. 5-31, figs 1-9, pls 1-8.

A view of the mound of the Kuhandiz of Herat with the Shrine of Shahzada Abu’l-Qasim to the left and that of Shahzada ʽAbdullah to the right.

The Persian term kuhandiz, often corrupted in local dialect to quhandiz, quhanduz, quhunduz or even kunduz (now the name of a town in Afghanistan), means “old fort” and was applied to the ruins of Sasanian forts and fortified towns in the early Islamic period. The site of the Kuhandiz of Herat is situated to the north of the late mediaeval town and fort, and the site was first recognised by J. P. Ferrier as early as 1857 to be the mound of the citadel of ancient Herat. The Kuhandiz of Herat is mentioned in the Hudud al-`Alam as early as the tenth century.

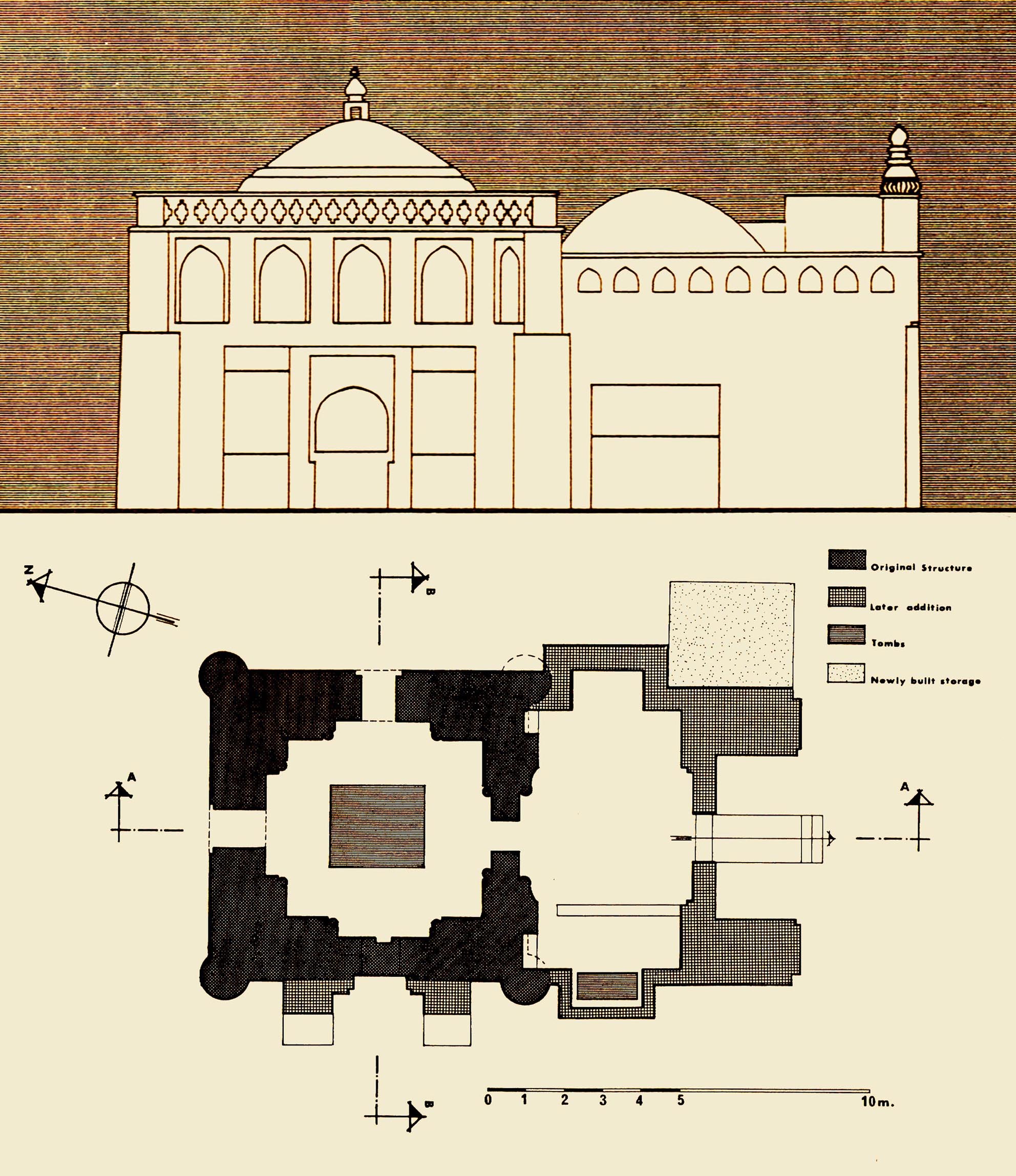

Today a vast graveyard occupies the site as well as two substantial shrines, highly revered by the local population, one attributed to be the shrine of Shahzada `Abd’ullah b. Mu`awiya and the other of Sahzada abu’l-Qasim b. Ja`far. The paper focuses on these two buildings and provides detailed architectural drawings. `Abd’ullah was a Shi’ite rebel and the great-grandson of Ja`far al-Tayyar, a brother of the Prophet’s son in law `Ali. `Abd’ullah revolted against the Umayyads in AH 127/AD 744-5 and after being defeated in several confrontations came to Iran to join the rebellions there and eventually died in Herat, where, according to the Mujmal-i Fasihi he was buried in the Kuhandiz. The date of the construction of the shrine is given in an inscription on the tomb as AH 865 (AD 1460), but in historical sources as 706 (1306-7) and 726 (1325-6).

The building is a typical Timurid structure and consists of a central octagonal domed chamber surrounded by a number of smaller chambers and a grand arched entrance. On the interior the lower parts of the walls are clad in fine Timurid tiles and above in-painted with geometric patterns in harmony with, but not exactly the same as, the motifs of the tiles. In the main chamber, all along the arches and vaults below the dome, runs an inscription in very fine naskhi script containing Quranic and religious texts.

The less elaborate, but more interesting structure is that attributed locally to be the shrine of Shahzada Abu’l-Qasim Muhammad b. Ja`far a-Sadiq, a son of the sixth Shi’ite Imam, although there are no reliable early records that this personage was buried in Herat. On the contrary, al-Tabari and other historians record that he died and was buried in Jurjan (present Gurgan in the Caspian region of Iran). Yet another fourteenth-century source mentions that he died in Sarakhs in north-west Iran and notes that at that time his shrine there was regarded with great respect. The tradition in Herat is best reflected in the Risala-yi mazarat-i Harat (Essay on the shrine of Heart):

The less elaborate, but more interesting structure is that attributed locally to be the shrine of Shahzada Abu’l-Qasim Muhammad b. Ja`far a-Sadiq, a son of the sixth Shi’ite Imam, although there are no reliable early records that this personage was buried in Herat. On the contrary, al-Tabari and other historians record that he died and was buried in Jurjan (present Gurgan in the Caspian region of Iran). Yet another fourteenth-century source mentions that he died in Sarakhs in north-west Iran and notes that at that time his shrine there was regarded with great respect. The tradition in Herat is best reflected in the Risala-yi mazarat-i Harat (Essay on the shrine of Heart):

The Prophet of God ... said on the night of the Ascent, Gabriel the Trustworthy showed me the shrines of earth. I saw a shrine with a pillar of light in it. I asked: "O Gabriel where is that shrine and what is in it?" Gabriel replied: "O Prophet of God, that is in Herat and that light is in the place where some of your offspring will be buried”.

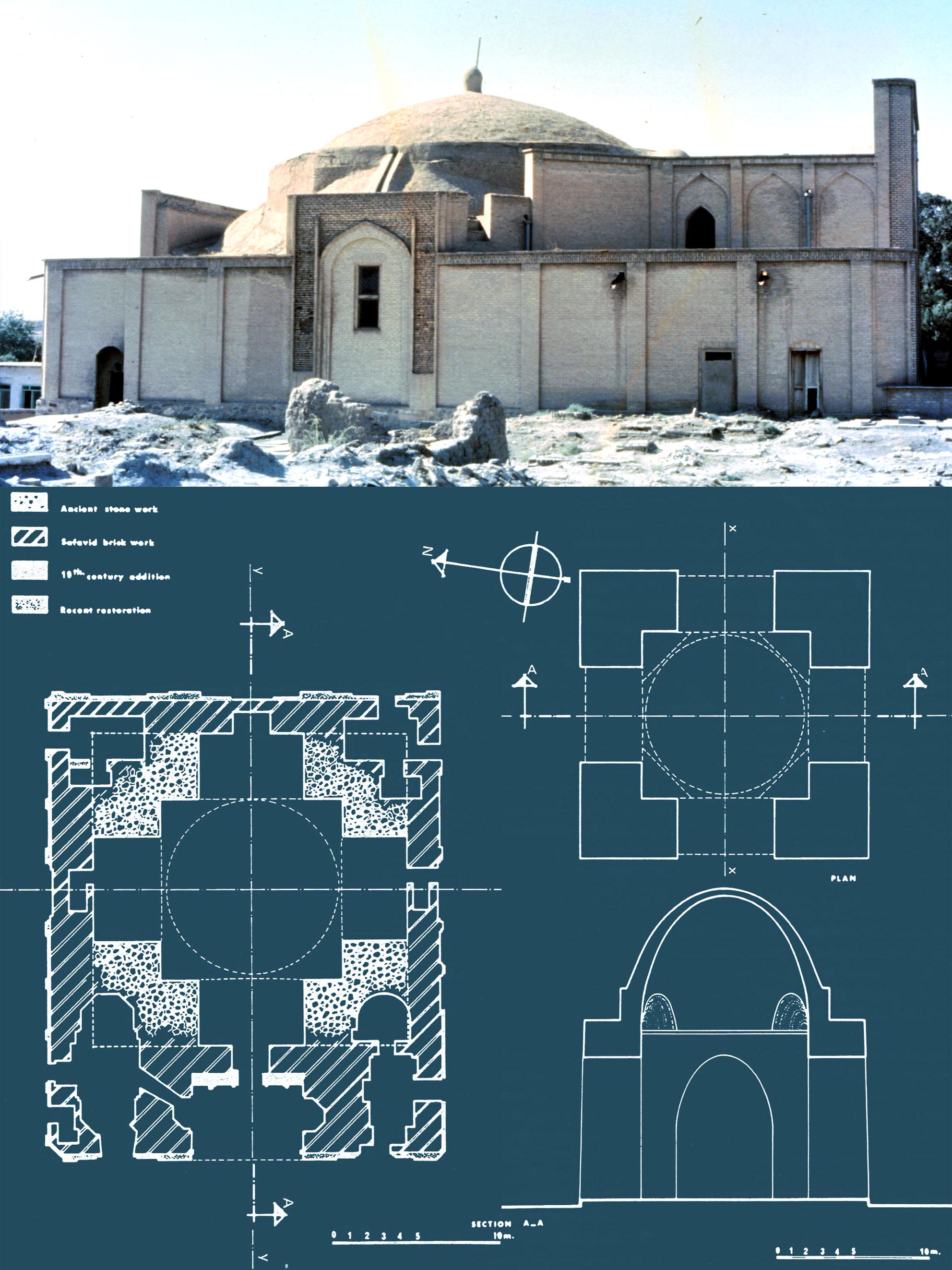

This legend reflects a persistent local tradition that “a pillar of light” – a fire – had existed in early times in the building. The survey of the building readily revealed that the plan and the massive piers, over three metres thick, are closely similar to those of a Sasanian fire temple. Further investigation and discussion with the representative of the shrine confirmed that the present brickwork is an envelope concealing a core built of stone set in a strong mortar containing “lead”. The presence of lead in the mortar could not be established but may just be a reference to the solidity of the mortar. The survey showed that the remains of the famous fire temple of Herat must have been converted to a Muslim shrine, the remains of the stone walls being squared up with brick and a dome built over the walls. If an illustrious person is buried in the shrine his identity remains uncertain. Reconstruction drawings suggesting the possible original appearance of the fire temple are given.

The shrine of Shahzada Abulqasim concealing the remains of

the renowned Sasanian fire temple of Herat. An impression

of the original plan and section of the fire temple is shown in

the drawings.

* “The Sasanian caravanserai of Dayr-i Gachin, south of Ray, Iran”, M. Shokoohy, BSOAS, XLVI, iii, 1983, pp. 445-61, figs 1-10, pls 1-8 (16 photographs). Translated into Persian in the Iranian Journal of Archaeology and History, vol. XX, nos. 1-2 Serial nos. 39-40, Spring-Summer 2006, 67-81.

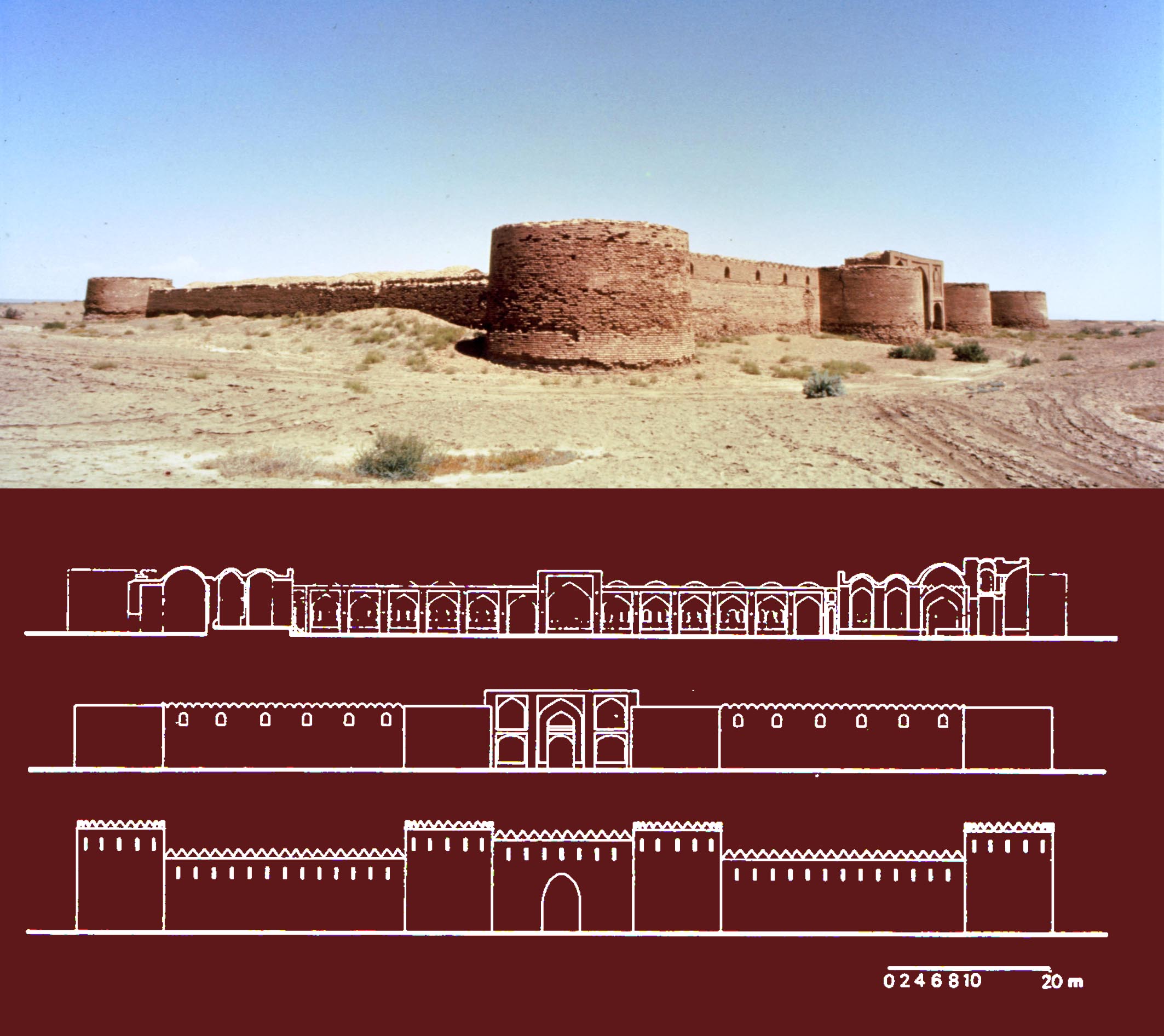

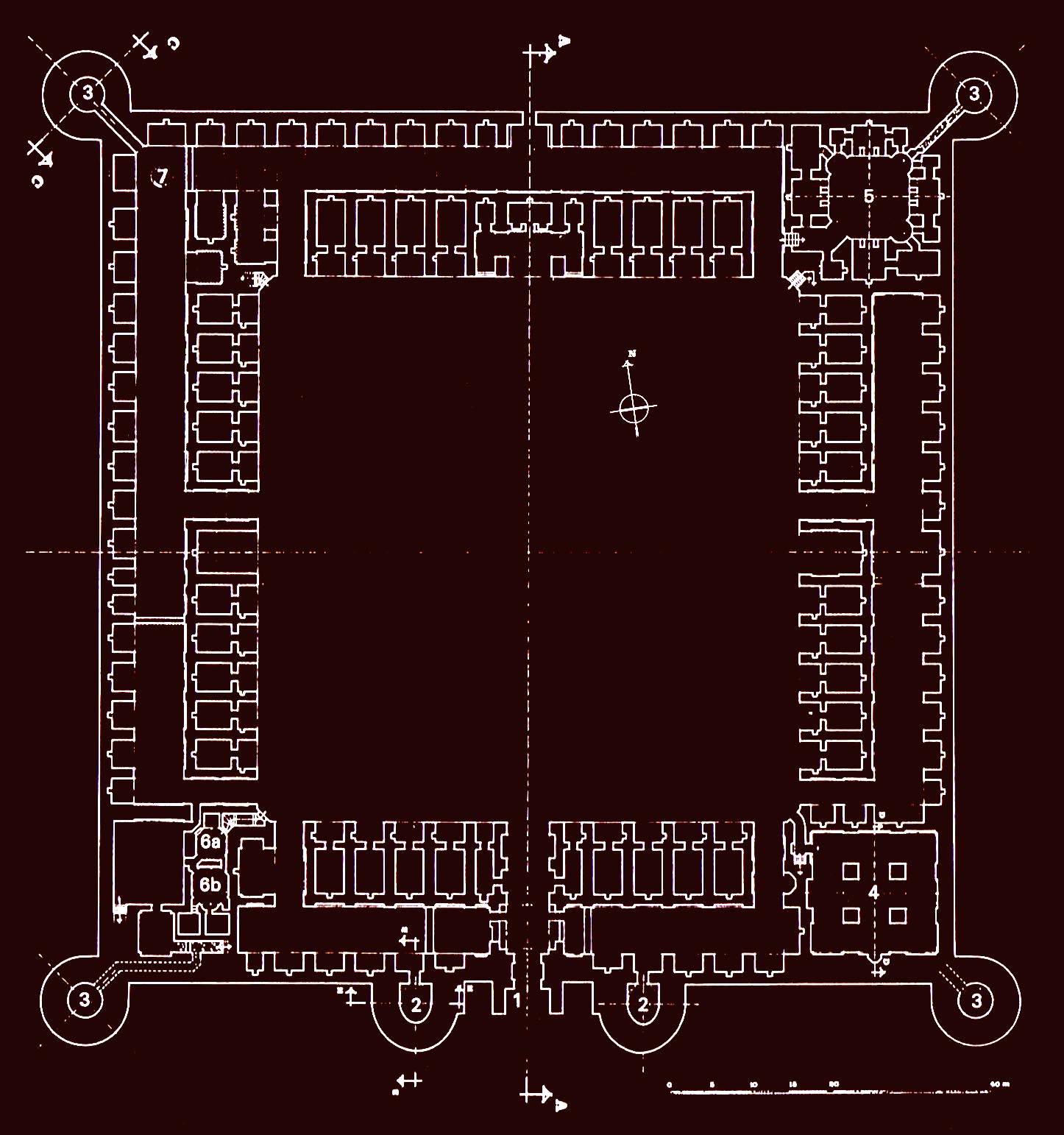

While the existence of caravanserais during the Sasanian period is generally accepted no substantial example had come to light before this publication. As well as being staging posts for travellers these complexes could serve as military posts for troops guarding the route and surrounding region. The word dayr means in general a monastery or loosely a rest-house, but in Persian lexicons the term is also given to mean a dome. The name could therefore be given literally as “the domed house of gypsum”. Dayr-i Gachin is situated in the desert, half-way between Ray and Qum, on the ancient route from Ray to Isfahan. The caravanserai is recorded in most early Muslim geographies, with its name sometimes given in Arabic as dayr al-jiss. According to Muhammad b. Qays al-Razi the name referred to a dome built with gypsum, which once stood there. Istakhri and Ibn Hauqal note that the caravanserai, “a huge stronghold of formidable construction”, was built of large fired bricks and gypsum, with a well of brackish water inside, and two circular cisterns outside to collect rain water for drinking. The caravanserai housed a garrison of the sultan's guards, apparently to maintain control of the route. The Sasanian origin of the caravanserai is mentioned by Abu Dulaf, Yaqut and Qazwini, among other early historians and while some, such as Yaqut, attribute it to the Sasanian Emperor Ardasir I, and give its Sasanian name as Kard-Ardasir, others record it as a work of Khusrow Anusiravan. It is not unlikely that the building dates from early Sasanian times, and was restored at the time of Anusiravan. During the Islamic period the caravanserai underwent major reconstruction at least twice. The first occasion was at the time of the Seljuq Sultan Sanjar and later during the Safavid period when most of the old vaults, built with large sized Sasanian bricks measuring 36 x 36 x 8 cm. were dismantled, and new vaults were built with small bricks of 25 x 25 x 5 cm. over the old walls. A large number of Sasanian bricks were left around the site, and were reused later in the surrounding buildings.

The caravanserai is a fortified square enclosure, with round towers at the corners and two towers, semi-elliptical in plan, flanking its main entrance at the middle of the southern wall. The corridors to the towers have kept their original parabolic vaults, and the towers themselves have preserved their Sasanian domes, which are again parabolic in profile. The domes of the entrance towers are elliptical in plan, unusual in Iranian architecture. Inside the enclosure the caravanserai has a large central courtyard surrounded by four iwans (open fronted vaulted chambers) and forty rooms, each with a vaulted veranda in front, and a row of stables behind with sixty-six raised niches in the walls, for use as sleeping platforms. The arrangement of the plan is similar to other Islamic caravanserais of Iran, and it is not clear how much of the layout is Sasanian, and how much Seljuq. Outside the enclosure the cisterns domed with Sasanian brick are also preserved, one of them still holding water.

The caravanserai is a fortified square enclosure, with round towers at the corners and two towers, semi-elliptical in plan, flanking its main entrance at the middle of the southern wall. The corridors to the towers have kept their original parabolic vaults, and the towers themselves have preserved their Sasanian domes, which are again parabolic in profile. The domes of the entrance towers are elliptical in plan, unusual in Iranian architecture. Inside the enclosure the caravanserai has a large central courtyard surrounded by four iwans (open fronted vaulted chambers) and forty rooms, each with a vaulted veranda in front, and a row of stables behind with sixty-six raised niches in the walls, for use as sleeping platforms. The arrangement of the plan is similar to other Islamic caravanserais of Iran, and it is not clear how much of the layout is Sasanian, and how much Seljuq. Outside the enclosure the cisterns domed with Sasanian brick are also preserved, one of them still holding water.

The extensive caravanserai offering shelter on the desert route. Drawings

show a section through Dayr-i Gachin as well as the front (entrance)

elevation showing its present condition and original Sasanian form.

Dayr-i Gachin is one of the largest caravanserais of Iran, and, apart from the usual accommodation has features which are not common in other caravanserais. Inside the enclosure each corner is built with a different plan for a specific function. At the north-west corner there is a mill, and the south-west has a small courtyard with a bath-house and kitchen. The north-east corner is built as exclusive accommodation around a small courtyard, and must have been for the use of royalty or high ranking officials. Among such personages was the Safavid Shah Ismaʽil I, who took this route on his campaign from Fars to Firuzkuh and Mazandaran. An interesting feature in the caravanserai is a mosque constructed at the south-east corner of the enclosure. The mosque is square in plan, and in the centre of the hall there are four massive piers of Sasanian brick, arranged like those of a chahar-taq, a dome standing on square plan with four piers with open vaults at each side, a form characteristic of Sasanian fire temples. As with the rest of the structure the original roof has been replaced by later Islamic vaults, but it is likely that the mosque is on the site of a Sasanian fire temple which had a domed chahar-taq

Dayr-i Gachin is one of the largest caravanserais of Iran, and, apart from the usual accommodation has features which are not common in other caravanserais. Inside the enclosure each corner is built with a different plan for a specific function. At the north-west corner there is a mill, and the south-west has a small courtyard with a bath-house and kitchen. The north-east corner is built as exclusive accommodation around a small courtyard, and must have been for the use of royalty or high ranking officials. Among such personages was the Safavid Shah Ismaʽil I, who took this route on his campaign from Fars to Firuzkuh and Mazandaran. An interesting feature in the caravanserai is a mosque constructed at the south-east corner of the enclosure. The mosque is square in plan, and in the centre of the hall there are four massive piers of Sasanian brick, arranged like those of a chahar-taq, a dome standing on square plan with four piers with open vaults at each side, a form characteristic of Sasanian fire temples. As with the rest of the structure the original roof has been replaced by later Islamic vaults, but it is likely that the mosque is on the site of a Sasanian fire temple which had a domed chahar-taq

in the centre.

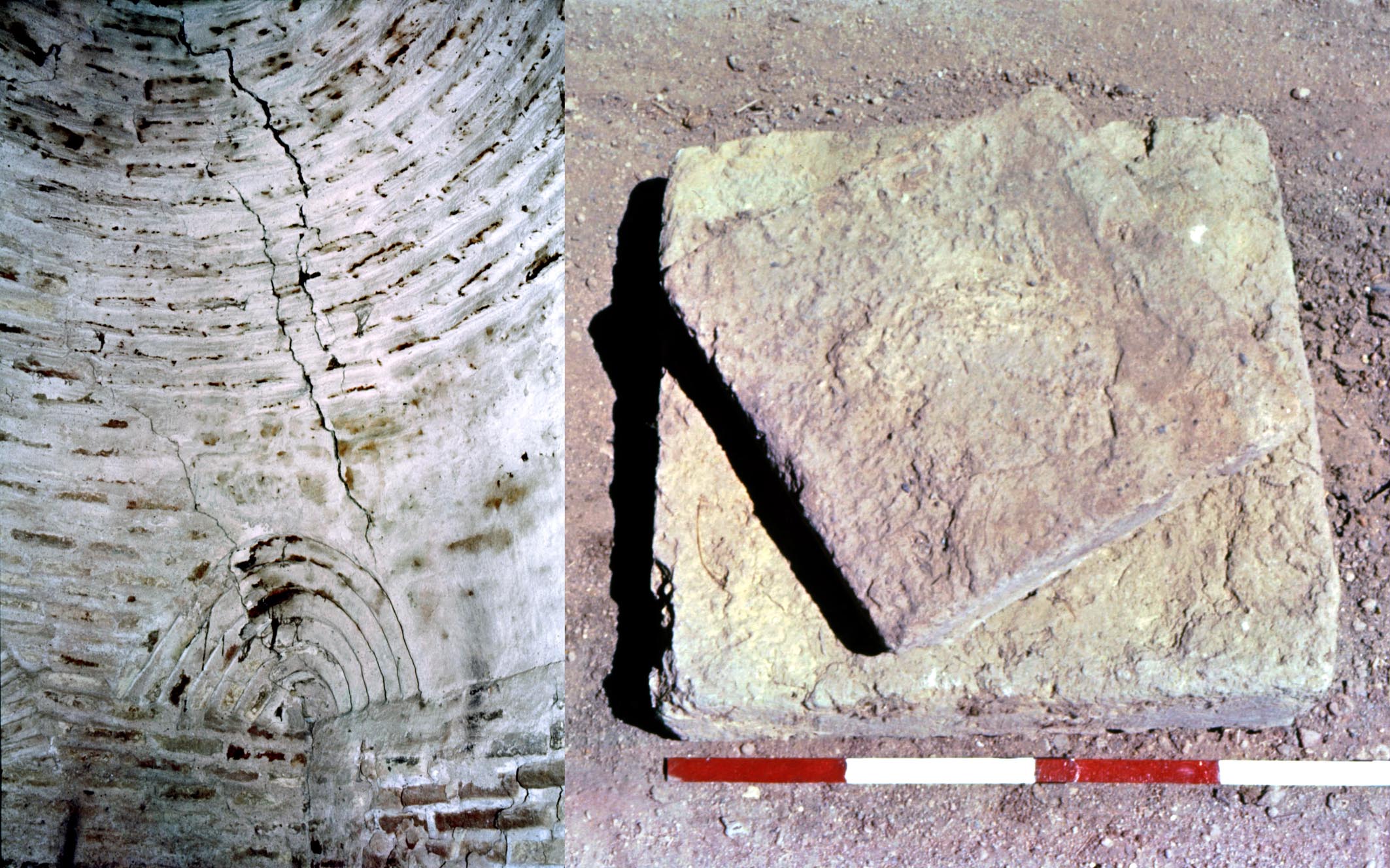

One of the original Sasanian entrance towers, elliptical in plan, with its parabolic dome of large bricks on parabolic squinches. Detail showing the contrast between the smaller size of an Islamic brick over a Sasanian one.

* “Two fire temples converted to mosques in Central Iran”, M. Shokoohy, in Papers in Honour of Mary Boyce, Acta Iranica, XXIV (Hommages et opera minora, vol. XI), 1985, pp. 545-72; translated into Persian in the Iranian Journal of Archaeology and History, V, ii, 1991, pp. 52-68.

* “Two fire temples converted to mosques in Central Iran”, M. Shokoohy, in Papers in Honour of Mary Boyce, Acta Iranica, XXIV (Hommages et opera minora, vol. XI), 1985, pp. 545-72; translated into Persian in the Iranian Journal of Archaeology and History, V, ii, 1991, pp. 52-68.

As a tribute to the renowned scholar of Zoroastrian studies Mary Boyce’s focus on belief and practice, a discussion on a complimentary aspect, physical evidence, is presented here.

In the Islamic world many places of worship of earlier religions have been converted to mosques. Examples are numerous, among them the Church of St. John in Damascus and Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. The same fate befell the Zoroastrian fire temples in Iran and Afghanistan. The conversion of the great fire temple of Herat to a shrine has already been discussed in the paper “The monuments at the Kuhandiz of Herat, Afghanistan”. The present paper considers two mosques, the Masjid-i Birun in Abarkuh (Abarqu) and the Jamiʽ mosque of Aqda, both in Central Iran, where there were Zoroastrian communities for many centuries after the Muslim conquest. The change in use of these two fire temples seems to have occurred a few centuries after the conquest.

Abarkuh, Masjid-i Birun, the structure of the domed fire temple

is preserved almost intact in the core (shown in solid black in the

plan), but there are some alterations and additions to other parts

of the building. The mosque displays the plasticity and elegance of

central Iranian mud architecture.

The historical background of the practice of converting buildings is considered, and the evidence concerning these two mosques investigated. An important piece of corroborating information is the orientation, which is not towards Mecca. A part of the paper studies mathematical methods of establishing an accurate direction for Mecca at any location in the world, and notes that while these very precise mathematical calculations were not always used by architects, they still had simpler methods to establish a fairly accurate orientation, which can be seen in almost all mosques in Iran. The marked deviation of these two mosques from the direction of Mecca is of itself a convincing argument for their pre-Islamic origin, but there is other evidence: the planning of the mosques conforms with that of fire temples and their Sasanian type of brickwork differs considerably from that of Muslim period. The inscriptions of both mosques also allude to their conversion, apparently as late as in the fifteenth century.

The historical background of the practice of converting buildings is considered, and the evidence concerning these two mosques investigated. An important piece of corroborating information is the orientation, which is not towards Mecca. A part of the paper studies mathematical methods of establishing an accurate direction for Mecca at any location in the world, and notes that while these very precise mathematical calculations were not always used by architects, they still had simpler methods to establish a fairly accurate orientation, which can be seen in almost all mosques in Iran. The marked deviation of these two mosques from the direction of Mecca is of itself a convincing argument for their pre-Islamic origin, but there is other evidence: the planning of the mosques conforms with that of fire temples and their Sasanian type of brickwork differs considerably from that of Muslim period. The inscriptions of both mosques also allude to their conversion, apparently as late as in the fifteenth century.

Masjid-i Birun, interior of the iwan (open fronted hall) with a Sasanian style elliptical vault, rather than a pointed one in the Islamic manner. The original arched opening, with later horizontal re-enforcement, leads to the domed chamber.

_Jami%60,_LOW.jpg?556) “The Masdjed Djame' of Fahradj”, M. Shokoohy, Iranian Journal of Archaeology and history, III, i, Autumn-Winter 1988-89, pp. 16-23, 95-96, 8 architectural drawings, 16 photographs.

“The Masdjed Djame' of Fahradj”, M. Shokoohy, Iranian Journal of Archaeology and history, III, i, Autumn-Winter 1988-89, pp. 16-23, 95-96, 8 architectural drawings, 16 photographs.

The Fahradj Jami`, one of the oldest mosques in Iran – if not the earliest ‒ set at one side of the urban square of the town, still retains many of its original features, including a representation of two grand doors executed in one of the walls of the mosque giving an illusion that this relatively small building opens to another majestic structure. The Jami` (congregational mosque) is one of the only two surviving mosques in Iran with an Arab type plan, the other being the well-known Tarikhana at Damghan. However, in Fahradj the Arab plan is combined with a Sasanian style superstructure employing vaulted ceilings and almost semi-circular but very slightly pointed arches. It also displays Sasanian style squinches and other decorative features.

The paper, originally written in English as part of Mehrdad Shokoohy’s doctoral thesis, has been translated into Persian under the auspices of Mr Naser Chegini and the editors of the Iranian Journal of Archaeology and History.

The Fahraj mosque, a rare survival of an Arab type of plan in Iran, as the form went out of use and the layouts of other early mosques were mostly altered in later dates. The Jamiʽ displays the transition of Sasanian structural forms to those of the Islamic era. These include abandoning Sasanian style parabolic squinches and vaults in favour of slightly pointed semi-circular ‒ and later four-centred ‒ arches and vaults.

* “The Shrine of Imam-i Kalan in Sar-i Pul, Afghanistan”, M. Shokoohy, BSOAS, LII, ii, 1989, pp. 306-14, figs 1-8, pls 1-12 (16 photographs).

* “The Shrine of Imam-i Kalan in Sar-i Pul, Afghanistan”, M. Shokoohy, BSOAS, LII, ii, 1989, pp. 306-14, figs 1-8, pls 1-12 (16 photographs).

In 1964, Professor A. D. H. Bivar, while searching for an illusive Sasanian bas-relief in Sar-i Pul, North Afghanistan, noticed two little-known early Muslim shrines and studied the smaller shrine, known as Imam-i Khurd, a simple structure of about the mid-eleventh century consisting of a small square domed chamber, but retaining several inscriptions, one commemorating the martyrdom of Yaha b. Zayd (d. AH 125/AD 742-3). Bivar also noted the larger shrine, the Imam-i Kalan and published two photographs, one of its fine cut-stucco mihrab. When thirteen years later the research for the present paper was carried out the stucco was missing – apparently cut out of the wall and sold. The larger shrine had also preserved some of its old inscriptions, and while only a fragment of the date survived on the text around the entrance, other inscriptions and architectural features indicated a twelfth century date.

The building is a sizable square domed chamber with a large entrance vault added to its front. The original chamber has a squat dome and four circular corner piers or towers with a row of niches on the upper register of the exterior. These features appear in the early Islamic architecture of greater Khurasan (present Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmanistan and the Khurasan province of Iran) as early as the tomb of Isma`il Samanid in Bukara datable to AH 295 (AD 907-8).

The entrance portal and antechamber of Imam-i Kalan

are later additions, but the elevation of the original

domed chamber displays traditional features of the twelfth

century type, including the corner towers and row of niches

below the roof parapet.

In structural form, however, Imam-i Kalan is among the latest examples of its kind, as in twelfth-century Khurasan the form began to change. The squat domes were abandoned in favour of domes standing over high drums. The decorative niches were also replaced by plain walls and in most cases corner towers omitted. However, with the Ghurid conquest of India at the end of the twelfth century a simpler modified version of the old form, without corner towers, was introduced to India. While few thirteenth-century tombs have survived, it is pointed out that in India an allusion to the niches on the upper register of square tomb chambers appears in many specimens of the fourteenth century and later. These are investigated in the Shokoohys’ continuing research.

Although most of the original cut-stucco of the interior is lost, what remains displays the elegance and sophistication of the designs as well as the very fine floriated Kufic script of the religious inscriptions.

“Darzin”, M. Shokoohy, EIr, vol. VII, fascicle i, 1994, pp. 83-84.

This entry is a summary of the paper “Monuments of the early Caliphate at Darzin in the Kirman region”. An abstract of the paper is given in its respective place.

“Dayr-e Gacin”, M. Shokoohy, EIr, vol. VII, fascicle ii, 1994, pp. 170-2.

This entry is a summary of the paper “The Sasanian caravanserai of Dayr-i Gachin, south of Ray, Iran”. An abstract of the paper is given in its appropriate place.

Please note the spelling as it appears in the Encyclopaedia Iranica.

Plan of the caravanserai of Dayr-i Gachin. It was outstanding in its time, and is mentioned in numerous early sources.

“Emam Saheb, two archaeological sites in Afghanistan”, M. Shokoohy, EIr, vol. VIII, fascicle iv, 1998, p. 391.

Afghanistan has two archaeological sites of this name: one consists of the ruins of an octagonal mud-brick fort of Sasanian origin, occupied up to the seventeenth century, in the village of Emam Saheb (Imam Sahib), near the south bank of the Amu Darya, about 50 kilometres north of Qonduz; while the other is a village in the Jauzjan region, south of the river Balkhab, halfway between Balkh and Aqcha.

This second site consists of several archaeological mounds, the remains of Sasanian and Islamic settlements. The most outstanding edifice is the well-known early Islamic tomb of Baba Hatem. About five kilometres northwest of the village is Qush Tappa, a circular mound with a square fort to its east. The mound seems to have been a Sasanian town, with the fort, apparently detached from the town, functioning as the citadel, but the site seems to have been reconstructed during the Ghaznavid and Ghurid periods. About three kilometres west of the village is Tappa Sala or Tappa Ḵhush, of Islamic origin, dating from the eighth to ninth century. The settlement might have been re-occupied briefly in the Timurid period. The entry provides a full bibliography of material for both Imam Sahibs.

The author’s name is given erroneously as Shokouhi.