Contributions marked with an asterisk (*) indicate principal publications, mostly on sites and monuments introduced to the scholarly world for the first time. The colour illustrations in this site are from our extensive slide collection, and may not be the same views as printed in the publications. Illustrations in our contributions to edited books are mainly in monochrome.

“Az iszlám művészet Indiában a korai iszlámtól a Nagy-Mughalok bukásáig (Indo-Islamic architecture from the sultanate to the early Mughal period)”, M. Shokoohy, chapter XII, in Géza Fehérvári, Az iszlám művészet története, (Képzömüvészeti Kiadó) Budapest, 1987, pp. 193-225, pls. 161-184, colour pls. 182-196.

“Az iszlám művészet Indiában a korai iszlámtól a Nagy-Mughalok bukásáig (Indo-Islamic architecture from the sultanate to the early Mughal period)”, M. Shokoohy, chapter XII, in Géza Fehérvári, Az iszlám művészet története, (Képzömüvészeti Kiadó) Budapest, 1987, pp. 193-225, pls. 161-184, colour pls. 182-196.

ISBN: 963 336 348 9

The work is a chapter in the late Professor Fehérvári’s book on Islamic art and architecture in Hungarian. The chapter, originally in English, was translated into Hungarian, but the original English version has not yet been published. Sultanate and Mughal architecture are discussed in general terms, as well as regional architectural styles, such as those of Nagaur and Bayana, which had not been given the attention they deserve in general books on Islamic architecture.

New Delhi, the mosque in the shrine of Kwaja Nizam al-din Auliya’, built of red and buff sandstone in the early fourteenth century. The layout of three interconnected domed chambers with the central dome built on squinches and standing higher than the side domes ‒ set on pendentives ‒ is a prototype for numerous mosques from that period to modern times.

“The Iranian influence on urban planning in India”, M. Shokoohy, Iranian Cities, ed. M. Y. Kiani, IV, Tehran, 1990, pp. 260-80, (12 architectural drawings and maps, 6 photographs) (in Persian).

“The Iranian influence on urban planning in India”, M. Shokoohy, Iranian Cities, ed. M. Y. Kiani, IV, Tehran, 1990, pp. 260-80, (12 architectural drawings and maps, 6 photographs) (in Persian).

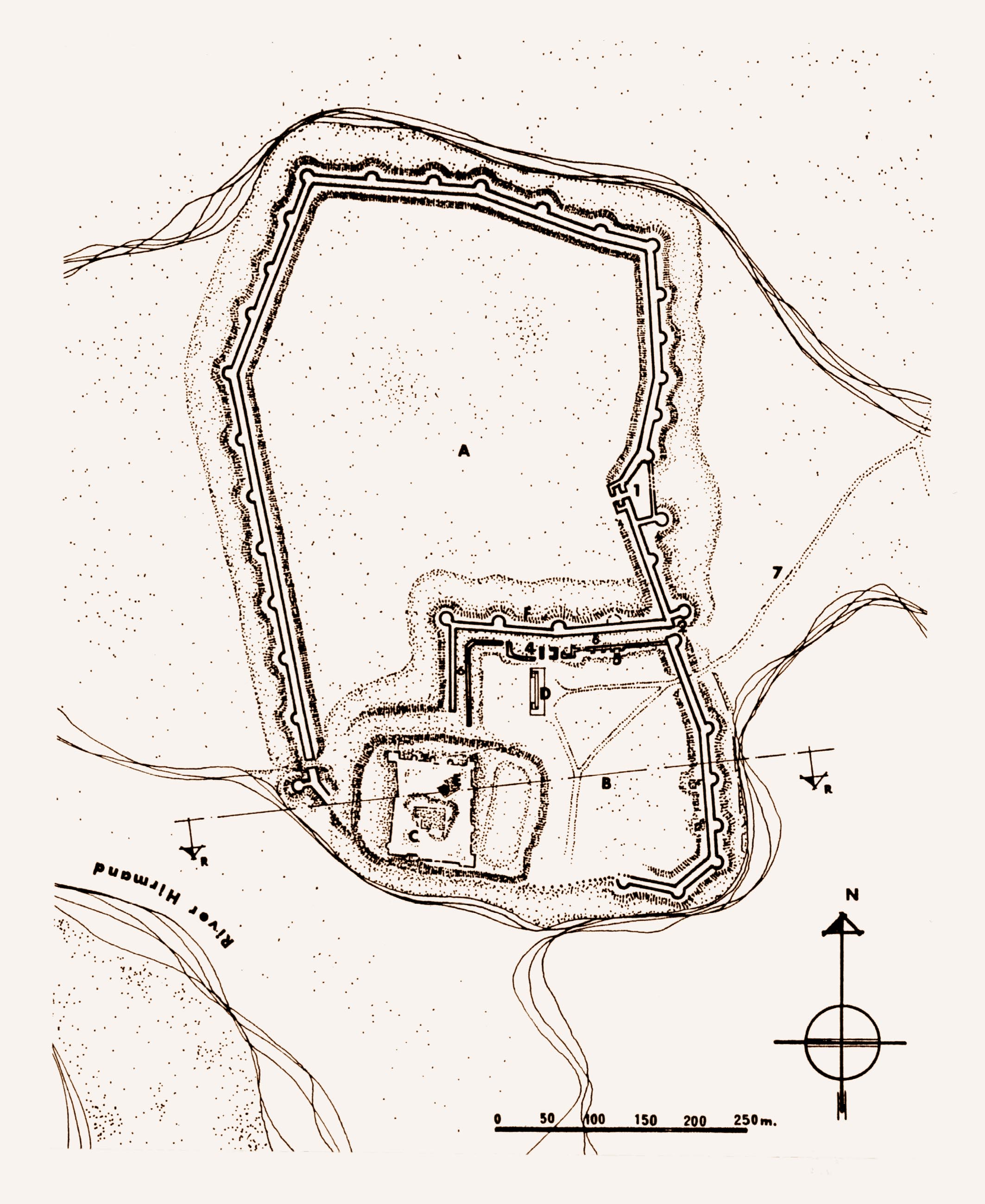

The chapter discusses the origins of the urban morphology of mediaeval Iranian towns, which rather than being concentric were planned with three components: the town itself, protected by a fort at one side, further guarded by a citadel at the perimeter of the fort, a more effective arrangement for resisting besiegers. It traces the origin of such forms in ancient towns of the bronze age in the mountainous regions of western Iran and analyses the development of the form in mediaeval times, when it was introduced to India. Indian cities built on such a plan are discussed, illustrating that this more defensible form became the norm there from the thirteenth century and the traditional Indian concept of concentric urban plans, based on sacred diagrams, was virtually abandoned. The paper, originally written in English has been translated into Persian and the original version has not been published, but the subject has been discussed in the Shokoohys’ other publications, including in Tughluqabad, a paradigm for Indo-Islamic urban planning and its architectural components and in “Pragmatic City versus ideal city: Tughluqabad, Perso-Islamic planning and its impact on Indian Towns”.

Town plan of Bust, Afghanistan, a city dating back at least to the Achaemenid period (c. 500 BC), but reconstructed in about the tenth century on a Perso-Islamic pattern with a citadel (arg), an upper town (bala-shahr) and a lower town (pa’in shahr). The city flourished under the Ghaznavids in the late tenth and eleventh centuries. Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna held court with his legendary “one thousand” poets there, and near the town built his army camp (lashkargah) and a palace. While Bust is now an uninhabited archaeological site the area is still known as Lashkargah.

* “Architecture of the Muslim trading communities in India” M. Shokoohy, Islam and Indian Regions, ed. by A. L. Dallapiccola and S. Zingel-Avé Lallemant, Beiträge zur Südasienforschung, Südasien Institut, Universität Heidelberg, 1993, CILV, vol. I, pp. 291-319, vol. II, References and Documentation, drawings nos. 7-20, pls. 45-60.

* “Architecture of the Muslim trading communities in India” M. Shokoohy, Islam and Indian Regions, ed. by A. L. Dallapiccola and S. Zingel-Avé Lallemant, Beiträge zur Südasienforschung, Südasien Institut, Universität Heidelberg, 1993, CILV, vol. I, pp. 291-319, vol. II, References and Documentation, drawings nos. 7-20, pls. 45-60.

The congregational (Jami`) mosque of Calicut, one of the

finest wooden mosques of Kerala. The oldest part (seen at

left and centre) dates from its restoration in 1480-1 AD,

but the building was extended in the late sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries when it was designated as the Jami`,

after the old Jami` (the Mithqalpalli) was burnt by the

Portuguese in 1510.

This paper, delivered in a conference at Heidelberg on Islam in India, and another article: Architecture of the Sultanate of Ma'bar in Madura and other Muslim monuments in South India, introduced the architecture of the maritime Muslim communities of the coastal regions of South India for the first time to the scholarly world. The Jami‘ of Cranganur and the main monuments of Calicut, including the Mithqalpalli, the Jami‘, the Muchchandipalli and the shrine of Sayyid ‘Abd’ullah were presented together with preliminary sketches (later improved and given in the monograph that completed the research project). The chapter, again for the first time, described the monuments related to the short-lived sultanate of Madura. These include the shrine of Sultan ‘Ala al-din and Sultan Shams al-din and the mosques of ‘Ala al-din and Qadi Taj al-din in Madura as well as the tomb of the last Madura sultan, Sikandar Shah, at Triuparangundram, on the site of his battle with the raja of Vijayanagar.

A pdf of the article is available, but for a full account of the sites discussed and comprehensive architectural drawings see the book: Muslim Architecture of South India.

“Bhadreshwar and the architecture of the early Muslim settlers”, M. Shokoohy, The arts of Kutch, edited by Christopher W. London, (Marg, vol. LI, no. iv) Bombay, 2000, pp 30-47, figs. 1a-6b (17 figures).

“Bhadreshwar and the architecture of the early Muslim settlers”, M. Shokoohy, The arts of Kutch, edited by Christopher W. London, (Marg, vol. LI, no. iv) Bombay, 2000, pp 30-47, figs. 1a-6b (17 figures).

ISBN: 978-8185026-48-0

After the publication of Bhadreśvar, the Oldest Islamic Monuments in India there were several requests for papers summarising the findings in that site. This is one such article, highlighting the major edifices of Bhadreśvar (or Bhadreshwar) for a wide readership in India.

Bhadresvar, the Chhoti Masjid, built for the Muslim maritime traders

by local Jain craftsmen. As with other Muslim buildings on the site, the

stonework is ornamented with traditional Indian designs but excludes

figurative elements.

Excavations at Ghubayra, Iran, by A. D. H. Bivar, assisted by P. A. Baker, G. Fehérvári, M. Shokoohy, S. Tyler-Smith and Linda Wooley, edited by M. Shokoohy (School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London) London, 2000, 558 pp., 87 figures, 144 plates.

ISBN: 07286 0307 1

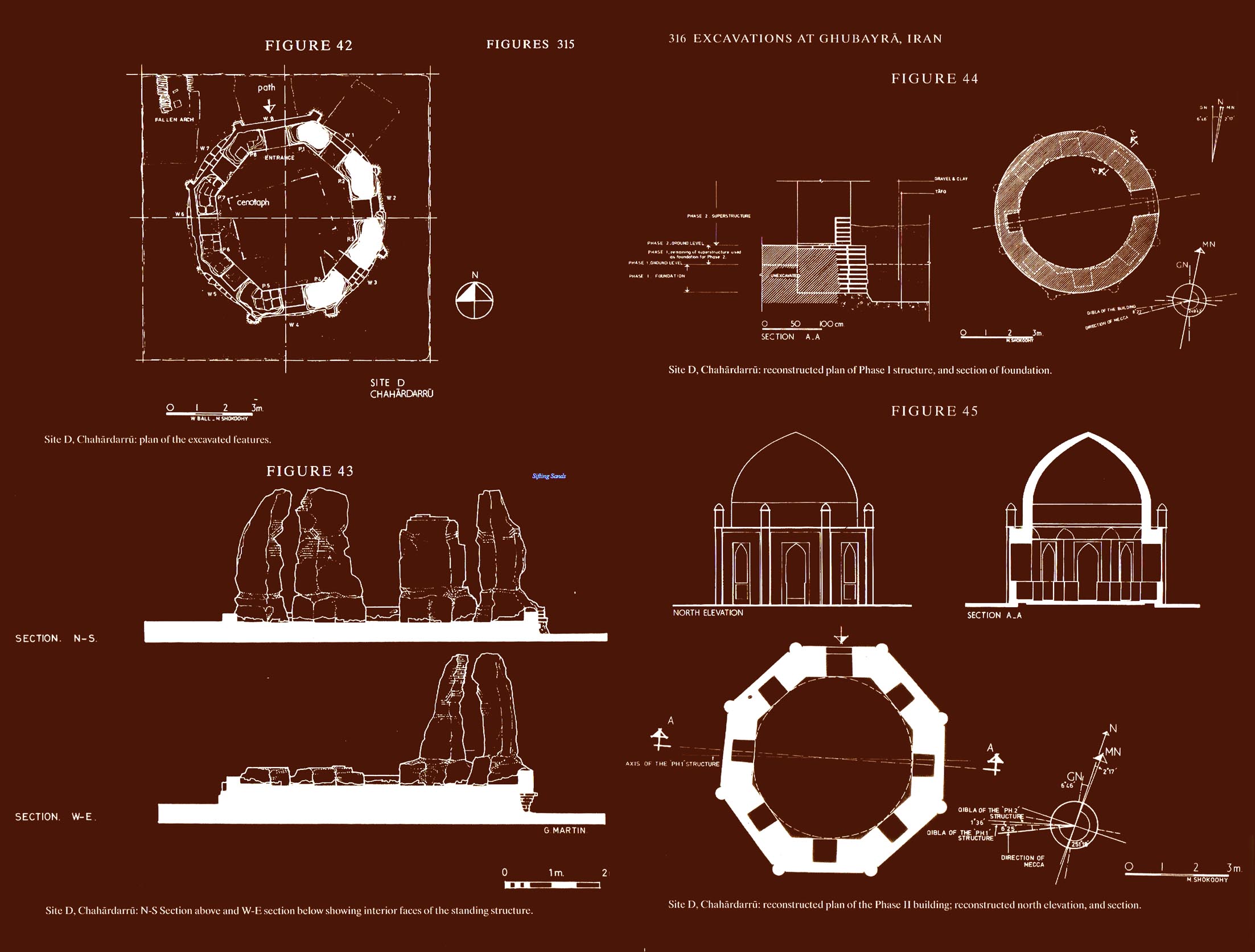

The SOAS project of Excavations at Ghubayra, an ancient and mediaeval site in the province of Kerman, Iran, was carried out in four seasons between 1971 and 1976 under the joint directorship of Professors A. D. H. Bivar and Géza Fehérvári. When the results of the excavations were being analysed in London, Mehrdad Shokoohy was the architectural consultant, responsible for reviewing the earlier drawings made on site, analysing and interpreting them, making amendments and in many cases producing new amended drawings of the excavated sites and the remains of the buildings, including conjectural reconstruction drawings.

Taking all the separate survey drawings from various excavated sites and plotting them in their respective locations he produced a master plan of the entire site, which clarified the relationship between the excavated areas. He also produced drawings of the specimens of iron objects which had been brought to London, and edited the final report of the whole site.

Taking all the separate survey drawings from various excavated sites and plotting them in their respective locations he produced a master plan of the entire site, which clarified the relationship between the excavated areas. He also produced drawings of the specimens of iron objects which had been brought to London, and edited the final report of the whole site.

The book can be ordered directly from SOAS, http://store.soas.ac.uk. E-mail: onlinestoreenquiries@soas.ac.uk

Survey drawings of the remains of an octagonal building, itself built over a circular structure of a type known as a tomb-tower. Although both structures were in ruins enough evidence was left to produce conjectural reconstruction drawings of the plan of the circular tower, and of the plan, sections and elevations of the later octagonal structure.

“The Architecture of Baha al-din Tughrul in the region of Bayana, Rajasthan”, M. and N. H. Shokoohy, Architecture of Mediaeval India: forms, contexts, histories, edited by Monica Juneja, (Permanent Black) New Delhi, 2001, pp. 413-428, figs. 1-11, (a reprint of the paper first published in Muqarnas, IV, 1987, pp. 114-32, figs 1-27).

“The Architecture of Baha al-din Tughrul in the region of Bayana, Rajasthan”, M. and N. H. Shokoohy, Architecture of Mediaeval India: forms, contexts, histories, edited by Monica Juneja, (Permanent Black) New Delhi, 2001, pp. 413-428, figs. 1-11, (a reprint of the paper first published in Muqarnas, IV, 1987, pp. 114-32, figs 1-27).

ISBN: 978-8-178240-10-7

This reprint of the paper published first in Muqarnas contains the full text of the original publication, but not all drawings and photographs. An abstract of the paper is given in its respective place under the entry for the original publication.

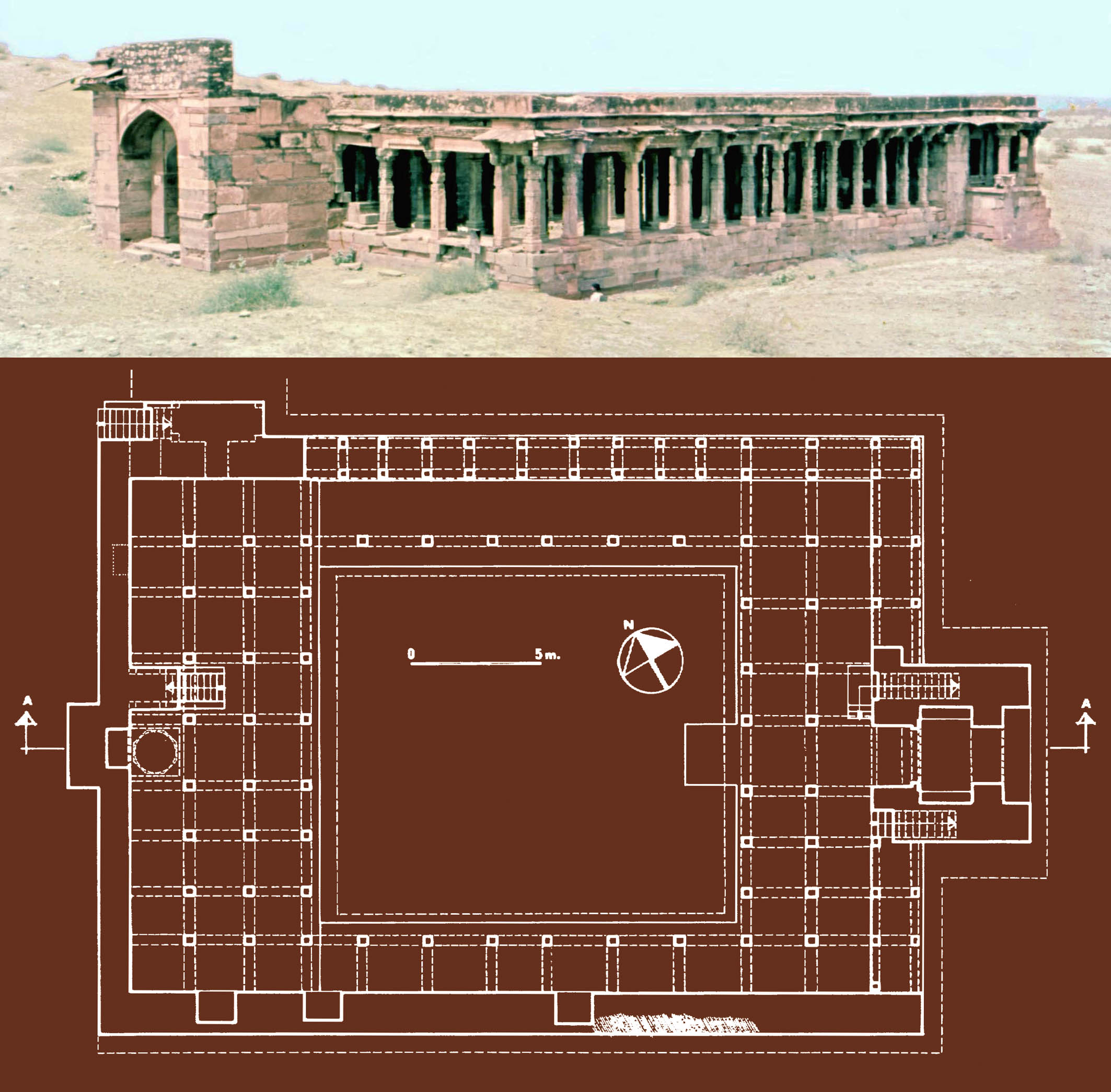

Kaman, the Chaurasi Khamba Mosque, bearing the inscription

of Baha al-din Tughrul. Built between 1195 and 1210 AD, it is

one of the earliest mosques of the sultanate period.

* “The Tomb of Ghiyath al-din at Tughluqabad: Pisé architecture of Afghanistan translated into stone in Delhi”, M. and N. H. Shokoohy, in Cairo to Kabul, Ralph Pinder-Wilson Festschrift, ed. Warwick Ball, (Melisende) London, 2002, pp. 207-221, figs. 22.1-22.10, pls. 22.1-21.9.

ISBN: 978-1-901764-12-3

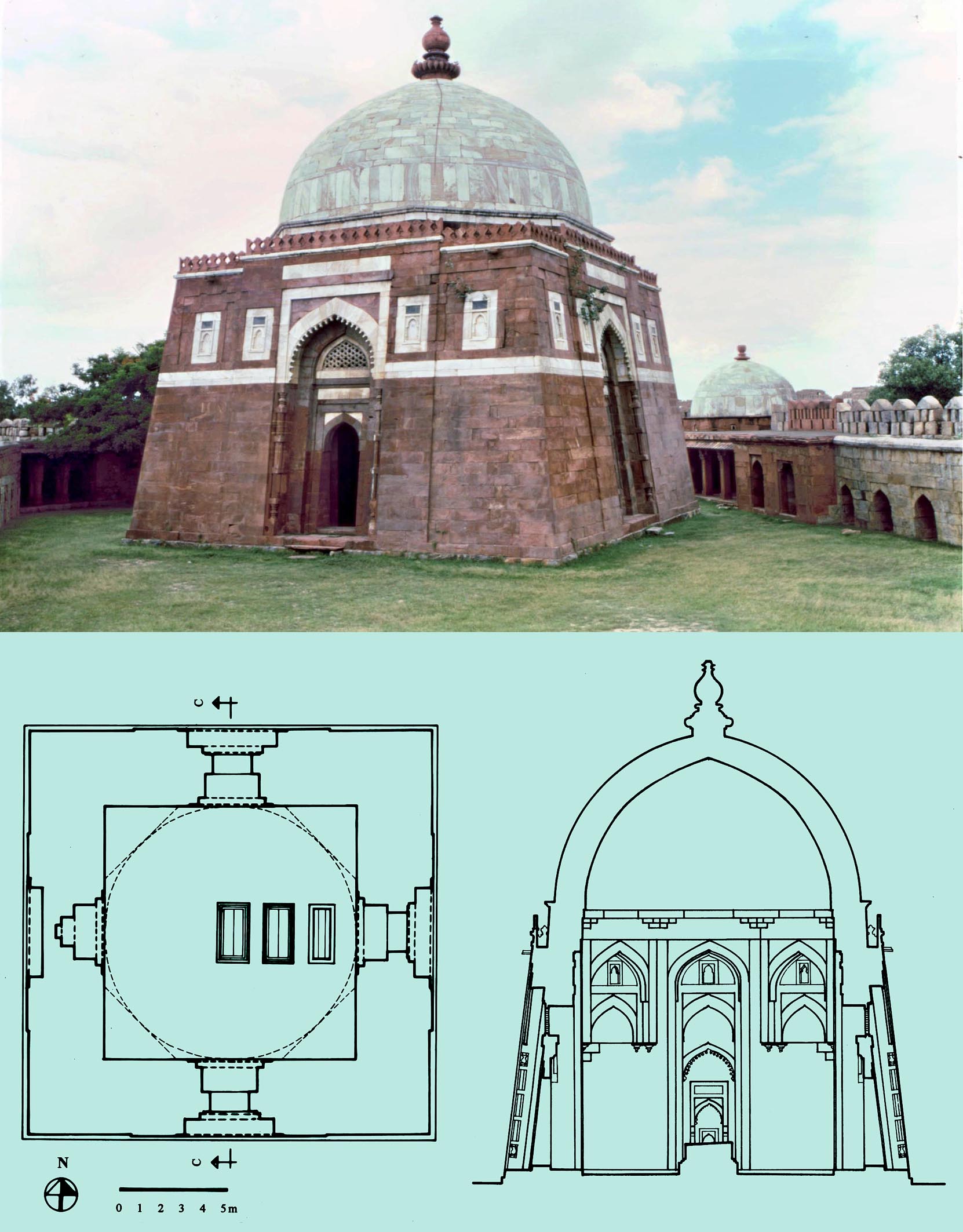

The tomb of Ghiyath al-din – a square domed chamber in the courtyard of a small octagonal fortified island south-west of the citadel – is the only monument of Tughluqabad which is well preserved and mentioned in most general works. Its innovative design, the delicate use of different coloured stone in its construction, and above all its imposing structure contribute to its recognition as an outstanding sultanate monument. The spirit of the tomb was perhaps best evoked by Fergusson as early as 1876:

“His tomb ... instead of being situated in a garden, as is usually the case, stands by itself in a strongly-fortified citadel of its own, surrounded by an artificial lake. The sloping walls and almost Egyptian solidity of this mausoleum, combined with the bold and massive towers of the fortifications that surround it, form a model of a warrior’s tomb hardly to be rivalled anywhere, and in singular contrast with the elegant and luxuriant garden-tombs of the more settled and peaceful dynasties that succeeded”.

The site, reached by a causeway across the lake, is integral to the master plan of the town. The tomb and its fortified enclosure echo the soaring walls of Tughluqabad, and Ibn Battuta informs us that the tomb was constructed by the order of Ghiyath al-din Tughluq himself and that when the sultan died his body as well as that of his young son Mahmud were brought to the sepulchre.

Tughluqabad, the tomb of Ghiyath al-din Tughluq. The battered

walls are a hallmark of the architecture of the Tughluq dynasty

and seem to have been adapted from the mud architecture of

Iran and Afghanistan.

The study of the mausoleum was part of the project of survey of Tughluqabad, and the article considers the history of the building and presents fresh and detailed survey drawings of the tomb chamber and its fortified enclosure, as well as an octagonal domed chamber in a corner of the enclosure housing the tomb of Zafar Khan, one of Ghiyath al-din’s army commanders, who died during the reign of the sultan. A version of this article has also been given as an appendix in the book: Tughluqabad, a paradigm for Indo-Islamic urban planning and its architectural components.

The Festschrift is available from major booksellers or directly from www.melisende.com

“Mi‘mari wa athar-i tarikhi-yi bengal (Architecture and historical monuments of Bengal)” (in Persian), M. Shokoohy, The Great Islamic Encyclopaedia, vol. XII, Tehran, 2004, pp. 605-608.

“Mi‘mari wa athar-i tarikhi-yi bengal (Architecture and historical monuments of Bengal)” (in Persian), M. Shokoohy, The Great Islamic Encyclopaedia, vol. XII, Tehran, 2004, pp. 605-608.

ISBN 978-9-647025-24-9

The paper was prepared at the request of the editors of The Great Islamic Encyclopaedia, for Persian readership, as the monuments of Bengal are almost entirely unknown in Iran, although there have been numerous publications on this topic in English. The paper discusses briefly the Muslim history of Bengal, and introduces its major monuments with a bibliography. It was originally prepared in English and translated into Persian by the publishers’ translators.

A pdf of the English version of the article is available.

Hadrat Pandua, the colossal congregational mosque built, unusually, with the prayer hall set at the longer side of the rectangular courtyard, recalling the mosque at Damascus, the only other celebrated mosque with such a layout. The Bengali structure, built of stone at the lower level and brick above represents one of the finest specimens of the architecture of the region.

“The Sidi Sayyid – or Sidi Sa‘id – Mosque in Ahmadabad”, M. Shokoohy, in: African Elites in India, eds. Kenneth X. Robbins and John McLeod, (Mapin Publishing) Ahmedabad, 2006, pp. 144-161, figs. 138-152.

ISBN: 978-1-890206-97-0

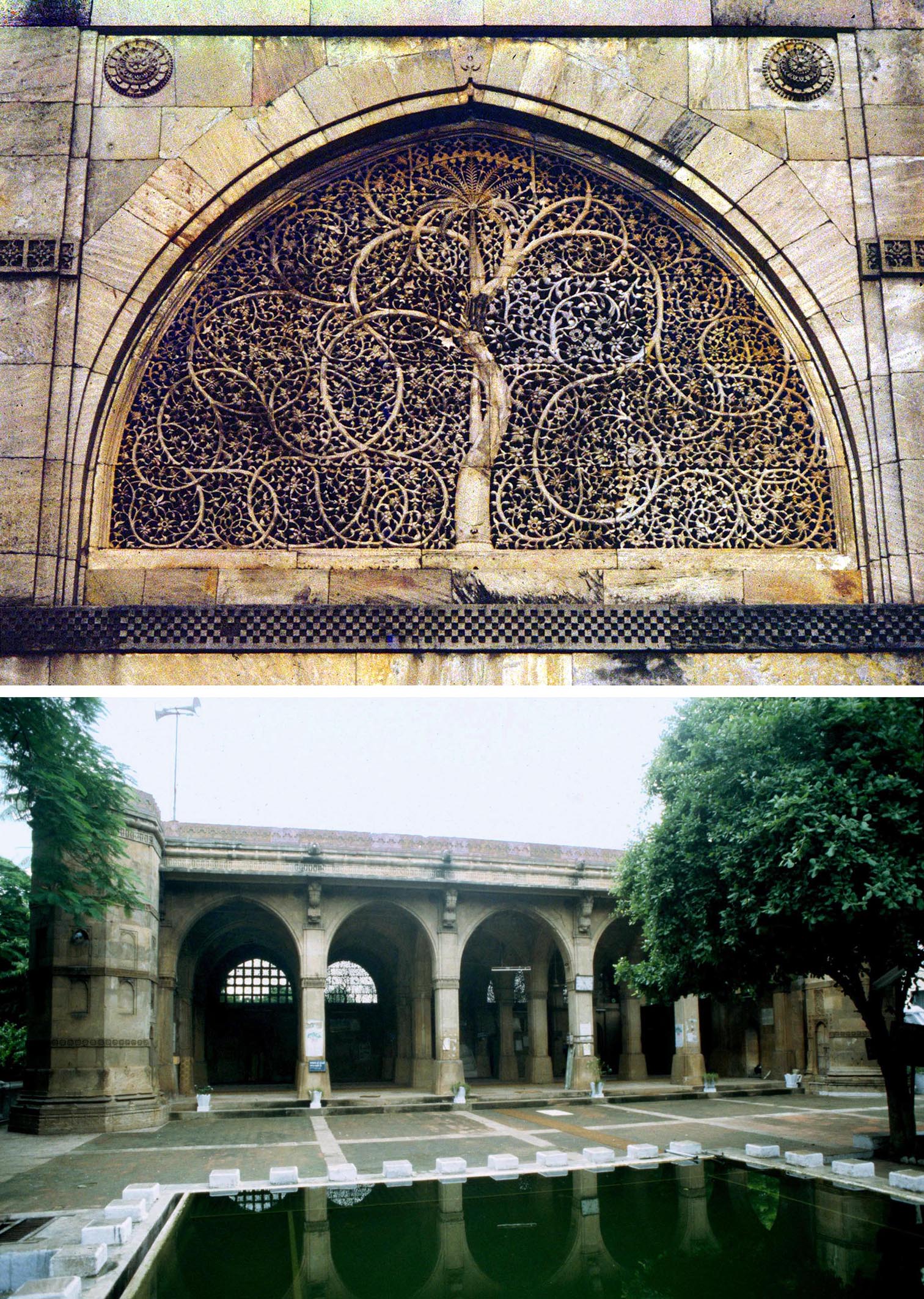

In the heart of old Ahmadabad, Gujarat, now by the side of a busy crowded road submerged in noise and smoke pollution, stands a small mosque; its austere architecture and fine stone carving offering a calm and tranquil retreat, and leaving those who enter it a lasting impression of its subtle charm. The mosque, commonly known as the Sidi Sayyid Masjid, is one of the smallest and latest monuments of the sultanate of Gujarat and yet is renowned world wide as a gem of Gujarati architecture. The building is on all tour itineraries, while its stone tracery has become almost an emblem for the city. Although the mosque is not in regular everyday use it is still regarded as a place of worship by the large Muslim community of Ahmadabad.

The mosque was first studied in some detail by James Burgess who called it Sidi Sayyad’s Masjid and carried out a survey of the building, published early in the twentieth century with architectural drawings as well as details of its carved panels, some of which are reproduced in the present work. However, he had little information on the history of the mosque. The local name suggested that the building was associated with the habashis (or habshis), the “Abyssinian” slave-soldiers – and administrators – of the court of Gujarat.

The paper gives a fresh description of the mosque and investigates its founder and the date of its construction through historical sources including the Gujarat historian Muhammad b. ‘Umar al-Makki, concluding that the mosque was constructed by Shaikh Sa‘id al-Habashi who was in the service of Sultan Mahmūd (AH 943–961/AD 1537–1554). In the brief but turbulent period after the death of the Sultan, when for a short time the habashis gained control, Sidi Sa‘id joined the service of Amir Jhujhar and is reported to have shown great courage and bravery. Shaikh Sa‘id later chose the quiet life of a learned and pious man of the faith. He had settled in Ahmadabad with apparently considerable wealth and it was at this period of his life that he built his famous mosque in AH 978 (1570-1 AD) and was buried near it when he died six years later. According to Muhammad b. ‘Umar al-Makki:

“In this year on Monday the 3rd of the month of Shawwal (24th December 1576) the brave and successful Shaikh Sa‘id of Abyssinia (al-habashi), known as the Royal Slave, died in Ahmadabad. In nature he was auspicious, of laudable qualities, possessed of all the principles worthy of elevation, with all ramifications of piety and was of encyclopaedic knowledge and adorned with virtues. His grave is in a mosque near the citadel on the main road. The mosque was originally an old building of bricks near his house. He rebuilt it with stone, elevated its stature and roofed it with domes and arches all with finely smoothed stone.... All around the walls of the mosque is decorated pierced stonework of excellent workmanship”.

A pdf of the chapter is available.

The book is available from major booksellers or directly from www.mapinpub.in

Ahmadabad, Gujarat, the diminutive mosque of Sidi Saʽid, its modest ornamentation relieved by the pieced stone screen-work (jali) of its windows, particularly those with the “tree of life” pattern set above and at either side of the prayer niche (mihrab). Soft light penetrating the jalis creates a tranquil ambience in the prayer hall.

* “The Indian ‘idgah and its Persian prototype the namazgāh or musalla”, M. and N. H. Shokoohy, in: Sifting Sands, Reading Signs: Studies in Honour of Professor Géza Fehérvári, ed. Patricia L. Baker and Barbara Brend, (Furnace Publishing, distribution: School of Oriental and African Studies) London, 2006, pp. 105-119, figs. 1-15.

ISBN: 978-0-955026-60-7

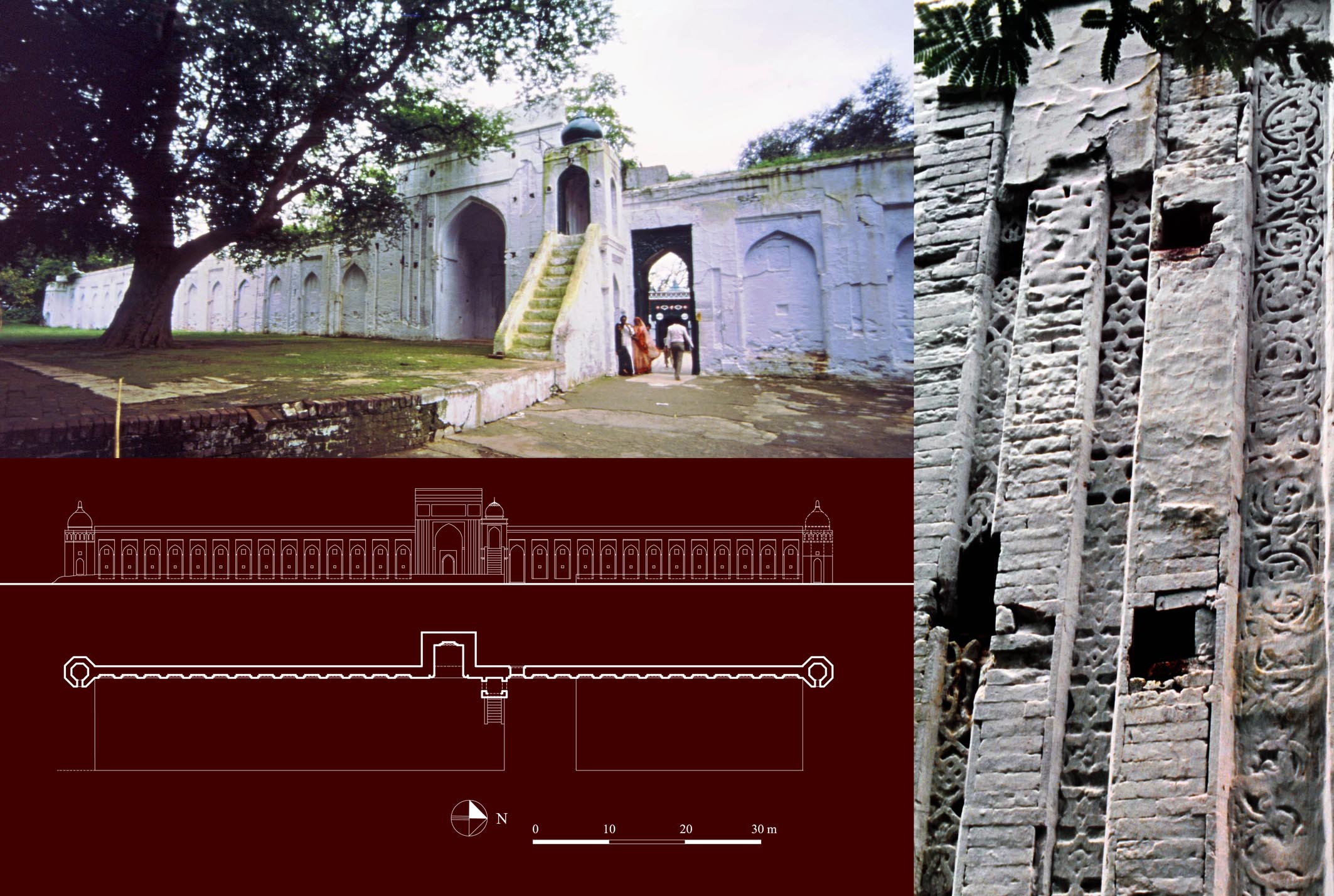

The ʽidgah of Bada’on, attributed to the time of

Iltutmish (AH 607-633/AD 1211-36) who also built

the original mosque, later heavily reconstructed

during the time of the Mughal emperor Akbar. The

‘idgah has also been restored many times, but its

plan with a large tower at each end and an iwan

(open fronted chamber) housing the prayer niche

has preserved its early layout. Until recently some

of the original decoration – characteristic of the

thirteenth century – could still be seen (shown on

the right), but the building has been plastered over

covering all the old ornamentation.

On the outskirts of many towns and villages in India there often stands an ‘idgah (literally a place for festivals), where the Muslims gather for prayer during a few particular festive days of the calendar, but which is left deserted for the rest of the year. Although a familiar sight, the origin and development of the form had not previously attracted the attention of the scholarly world.

The structures consist of a sizeable wall, often with a reinforcing pier or tower at each end and a mihrab (prayer niche) indicating the qibla (the direction of Mecca) in the centre, sometimes flanked by subsidiary mihrabs. The back of the wall is plain, but the main mihrab usually projects outside the wall, not only to distinguish the feature as a prayer wall, but also to reinforce the structure. The prayer walls are traditionally built facing an open field, away from buildings, tombs and graveyards, and are often – but not always – without a fence or low wall to distinguish the limits of the prayer ground; the size of the gathering is not usually constrained by a specific marked space.

Each town or village traditionally has only one ‘idgah, and in the past if a town expanded and building a new prayer wall, away from the built up area, was deemed necessary, the older ‘idgah would be demolished. The role of the ‘idgah in the life of the people went well beyond a simple congregation place for prayer, as on those festive days the gathering had an atmosphere of celebration, joy, and fun. Such a scene in pre-Partition India, with the whole town turning out, and hawkers selling sweets and knickknacks on the way, is depicted by the Urdu writer Prem Chand in his short story “‘Idgah”. However, in modern times in many of the larger cities of India the tradition of gathering for Muslim festivals is declining and with the sudden expansion of towns and villages some ‘idgahs have been demolished altogether to give way for new buildings and many others which are preserved are confined within built-up areas.

The paper investigates the origin of the form in tenth and eleventh century Iran and the introduction of these features to India at the end of the twelfth century. It also examines how the form developed very differently in later years in Iran and in India; in Iran the plain prayer walls developed gradually in substantial structures with chambers which could become as complex in layout as mosques, whereas in India the ʽidgah became plainer in form and ended up as a simple wall with a pier at each end for stability.

The articles of the festschrift were written by Géza Fehérvári’s colleagues in celebration of his 80th birthday.

Sifting Sands is out of print but a pdf of the chapter is available.

* “Sources for Malabar Muslim Inscriptions”, M. Shokoohy, in: Malabar in the Indian Ocean: Cosmopolitanism in a Maritime Historical region, ed. Mahmood Kooria and Michael Naylor Pearson, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2018, 1-63, figs 1.1-1.27.

ISBN-13: 978-0-19-948032-6

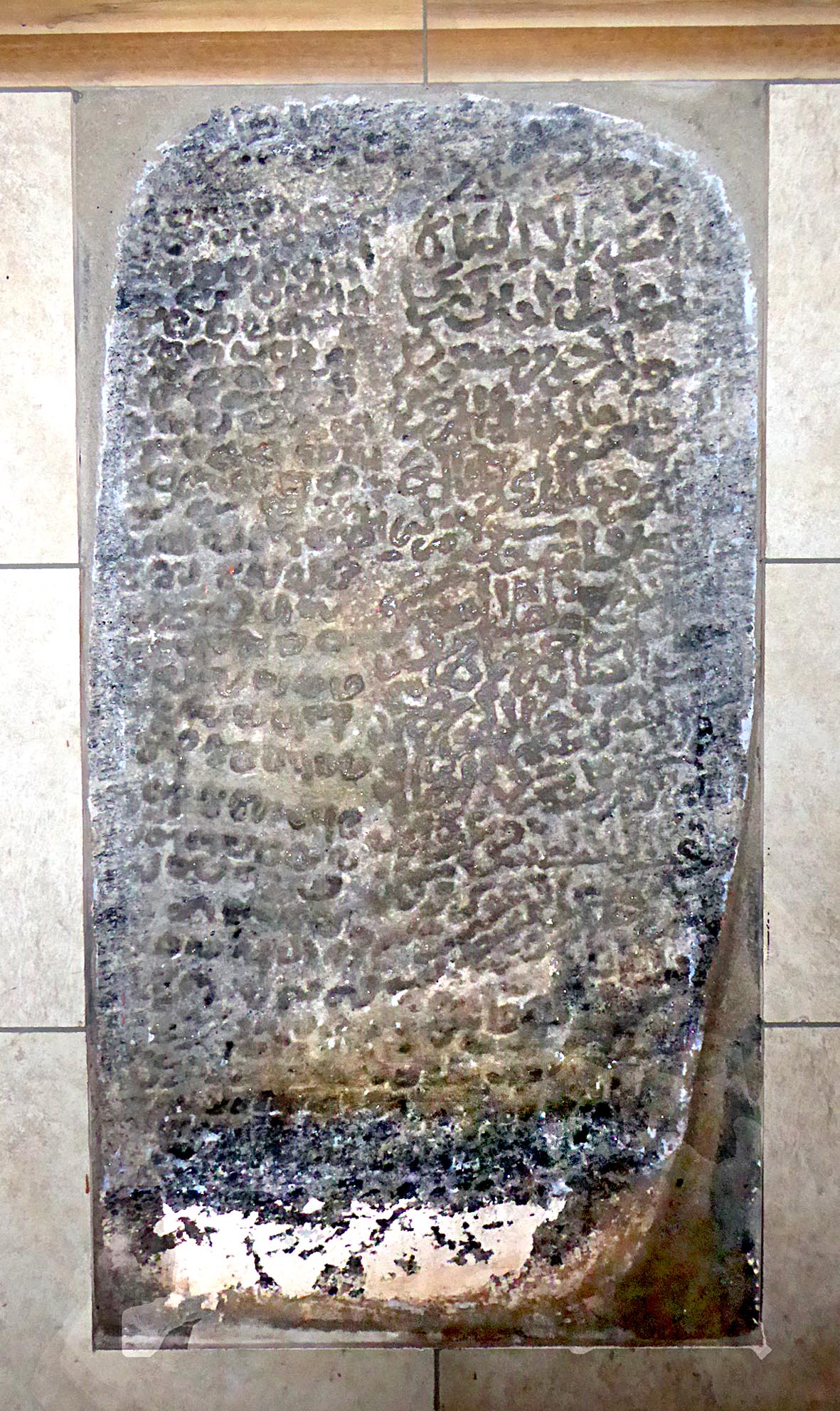

Calicut, the foundation stone of an early mosque preserved in the Muchchandipalli recording the construction of a mosque and the excavation of a well. The panel is likely to date from the thirteenth or early fourteenth century and while the date is eroded a reading of 686/1287–8 may be suggested.

As with all regions of South Asia, the inscriptions of Malabar stand as incontrovertible historical records, as, unlike manuscripts, they are not subject to error or misinterpretation of ambiguous words by later copyists. The epigraphs speak to us directly from the time of composition, setting out the composers’ aims and perception of their social position as well as revealing the community’s attitude to itself and outsiders. The Malabar maritime Muslims were a small, but affluent, influential, minority and their inscriptions often include both historical and religious texts, recording dates, sometimes events, and usually the name of the patron of the project. With epitaphs the historical text usually provides the date of an event or the death of the deceased, with names sometimes comprising a lineage, indicating position in society as well as the town or region of origin. Such information is revealing for understanding the composition of the communities.

The major inscriptions in Quilon (Kollam), Calicut (Kozhikode) and Cochin (Kochi) are investigated in detail, analysing their significance. Some inscriptions provide material evidence for the presence of Muslim communities at least from the 13th century while others attest to the revival of Muslim influence in the region, after an interruption caused by the advent of the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean and their challenge to Muslim maritime trade.

A comprehensive chronological list is then given of all known Muslim inscriptions in Malabar, mentioning their location and giving reference to sources. Most of these inscriptions have simply been noted in the epigraphic reports, but have so far remained unstudied. Nevertheless, the list provides valuable social and historical information. Most of the tombstones seem to have been worn out, but the names of the deceased give revealing information on the composition of the community. Together the inscriptions of the edifices and the epitaphs speaks of the close network of Muslim communities in the trading posts of India and beyond.

A comprehensive chronological list is then given of all known Muslim inscriptions in Malabar, mentioning their location and giving reference to sources. Most of these inscriptions have simply been noted in the epigraphic reports, but have so far remained unstudied. Nevertheless, the list provides valuable social and historical information. Most of the tombstones seem to have been worn out, but the names of the deceased give revealing information on the composition of the community. Together the inscriptions of the edifices and the epitaphs speaks of the close network of Muslim communities in the trading posts of India and beyond.

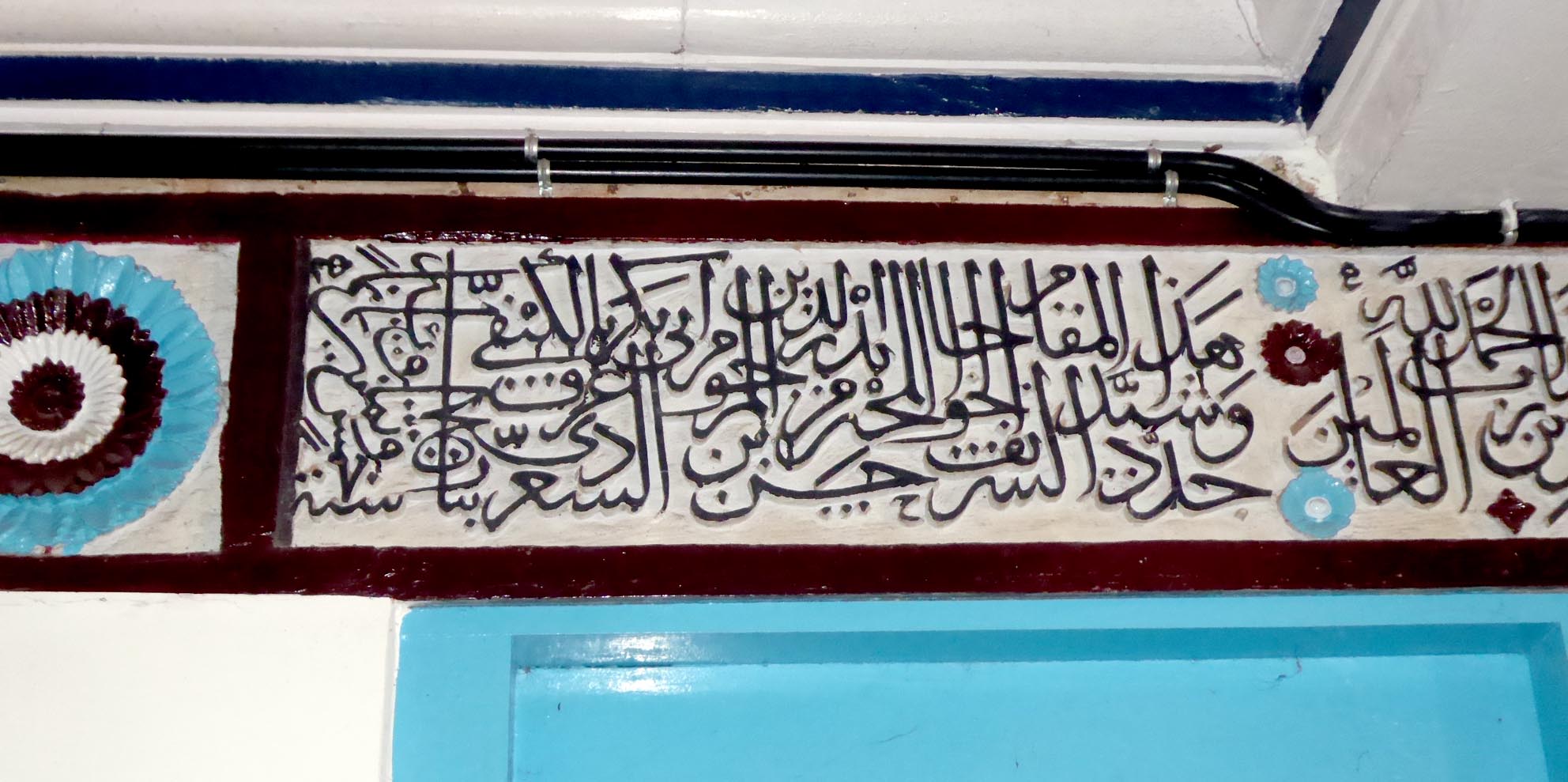

Calicut Jami`. The panel over the entrance

to the prayer hall recording the renovation

of the mosque in 885/1480–1.

It is hoped that the list will provide a stepping-stone for scholars to continue with detailed studies. The list is followed by a critical overview of such records, noting that in spite of the previous lack of proper investigation, considerable historical and social knowledge can be gleaned from their perusal.

* “The Malabar Mosque: a visual manifestation of an egalitarian faith”, M. Shokoohy and N. H. Shokoohy, in: Malabar in the Indian Ocean: Cosmopolitanism in a Maritime Historical Region, ed. Mahmood Kooria and Michael Naylor Pearson, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2018, 307-337, figs 11.1-11.23.

ISBN-13: 978-0-19-948032-6

Calicut, interior of the central part of the Jami` looking towards the mihrab

Calicut, interior of the central part of the Jami` looking towards the mihrab

and giving an impression of how the original mosque would have looked. The

modern blue and white paint has altered the original appearance, as the

wooden columns and ceiling would have been oiled and probably stained

with subtle colours.

The Indian Ocean trade did not begin with the Muslims. From the time of the ancient Greeks, Persians and Romans, people of many faiths – Jews, Christians and Zoroastrians – had settled on the India littoral, but no other maritime community had such a profound effect on the culture of their hosts as the Muslims, with the mosque as the architectural manifestation of their principal belief. While similarities can be drawn between the structure of the Malabar temples and mosques there was no parallel between them in concept or architectural planning. In a temple the gates and halls barred non-Hindus, outcastes and low castes from entry. Even for those allowed to enter, the dark inner sanctum of the temple was reserved for the Brahmins who performed the ritual on behalf of others. A mosque, on the other hand was a bright airy hall open to all. The prayer hall had no image of the sole invisible Almighty as a focal point, instead the worshipers prayed in the direction of Mecca, marked by a simple niche in the western wall. To all these differences one should add the concept of the khutba, the sermon usually delivered after the Friday prayer by the religious leader, guiding the faithful to the right path and furthermore giving the community – made up of merchants from different parts of the world – a sense of unity under the aegis of their single faith.

The planning of the Malabar mosques, consisting of an ante-chamber in front of the prayer hall differs from that of the sub-continent inland where there is no such ante-chamber. In Malabar a colonnaded porch often fronts this ante-chamber, a feature again absent in other Indian mosques. The Malabar mosque plan seems to be specifically related to the architecture of the trading communities and its roots can be traced back to the earliest Muslim settlements in Gujarat.

In structure, however the buildings employ the existing local traditional methods. This characteristic of the architecture of the maritime Muslims derives from the practice of hiring local craftsmen and using readily available material for building work. In the wider arena, the planning of the Malabar mosques resembles closely that of other coastal regions of India as well as lands further away – Malaysia, Indonesia and elsewhere – and in all these places local construction methods are employed, leading to striking similarities between the mosque architecture of Malabar and of South-East Asia.