|

|  |  |

|

|

Publications are given in reverse chronological order. Those marked with an asterisk (*) indicate principal publications, mostly on sites and monuments that have been introduced to the scholarly world for the first time.

ABBREVIATIONS:

BSOAS: Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London (Cambridge University Press)

ISSN: 0041-977X EISSN: 1474-0699

Available by subscription from Cambridge Journals Online

EI3: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Third Edition (E. J. Brill, Leiden-Boston)

ISSN: 1873-9830

Available on the Encyclopaedia of Islam website, http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/browse/encyclopaedia-of-islam-3

Architectural Diversity in South Asian Islam (Natalie H. Shokoohy), Chapter 8 Architectural Diversity in South Asian Islam (Natalie H. Shokoohy), Chapter 8

in South Asian Islam, A Spectrum of Integration and Indigenization, Nasr M. Arif

and Abbas Panakkal (eds), Routledge, Oxford – New York, 2024 pp. 187- 213 and

figs. 8.1-8.15,ISBN 978-1-032-45170-1 (Hardback), 978-1-032-57475-2 (Paperback)

978-1-003-43953-0 (e-Book)

Indo-Muslim architecture is striking for its combination of techniques and styles, stemming from the association

of the subcontinent with other lands through trade, invasion and settlement. The early maritime traders used

indigenous beam and bracket methods and a restrained local ornamentation, employing Jain and Hindu

craftsmen for their religious structures. The earliest surviving buildings of one of these trading communities are at Bhadreśvar, where an ancient Jain temple and centre of pilgrimage exists to this day. Bhadreśvar, on the coast of Kachchh (Kutch) in Gujarat, was once a magnificent ancient port. It was known to Ptolemy in the second century as Bardaxema and to al-Bīrūnī, writing in the eleventh century as Bhadra. The overseas traders dealt with the council of Jain merchants of the town, and a local Sanskrit chronicle mentions the Muslim community as “foreigners” of the Ismāʿīlī sect. The Jains gave the Muslims permission to build, and the most important Muslim building there is the shrine of Ibrāhīm, with its inscription of 554/1159-1160, the earliest date in situ on a monument in India. The environs of the shrine include two mosques: the Solahkhambī Masjid, and the Chhoṭī Masjid, all erected by local artisans.

The shrine consists of a square chamber with a corbelled dome, using the local technology, and on a plan which can be seen as a synthesis between Jain and Muslim architectural traditions. The miḥrāb, however, with its semi-circular plan and semi-circular arch, is in the style associated with Syria, Egypt and North Africa. A portico fronts the entrance featuring a flat ceiling decorated with a grid of squares with lotus patterns, which could be seen as a direct borrowing from temple architecture. The building, like all the Muslim buildings on the site, is constructed of large blocks of stone, a well-known method in India from ancient times, wiyh components including monolithic column shafts surmounted by brackets supporting lintels, roofed with flat slabs and corbelled domes.

Bhadreśvar, Kachh, Gujarat, above: Shrine of Ibrahim, the earliest standing Muslim building in

India. The concept of burial with a monument would have been unprecedented to the Jain host

community. Below: the Chhoṭī Masjid, a small mosque built by Muslim maritime traders with the

trabeate technology of a Jain or Hindu temple, but on a plan in accordance with the liturgical

requirements of a mosque. The porches in front of both buildings can be seen as a borrowing

from the concept of the maṇḍapa or open hall in front of a temple, and is a feature of the

mosques of Indian littoral

South India: shared technology of tiered wooden structures over stone walls. Left: the Mithqālpaḷḷi, a mosque built by merchants at Calicut.

Right: Bhagavati Temple at Cochin (Kochi). In spite of a superficial resemblance, the mosque’s planning makes it permeable and open from

the outside (the additions in the foreground are modern) while the temple interior is exclusive sacred space and out of sight.

Section of the west end of the Mithqālpaḷḷi showing its roof

structure with an example of its ancient antecedents, an

early fifth-century Buddhist wall painting from Cave 17 at

Ajanta depicting the roof space of a timber structure,

probably a monastery.

Travelling south, the architecture of the maritime traders in settlements all down the western and southern coasts of India again incorporates local building techniques and materials with the religious and social requirements of the traders. On the tropical coasts the traders would have found the main building material to be timber, and tiered structures the norm, from simple houses ‒ with the upper tiers providing airy lofts and at ground level patios protected from the sun and rain by deep overhanging eaves ‒ to elaborate multi-tiered temples.

The outer walls of the structures may be stone, but the joinery of the wooden superstructure employs pegs rather than nails and has ancient precedents and a wide geographic scope, being seen throughout South-East Asia and as far as China and Japan. The system used for laying beams and rafters is depicted in wall paintings in the Buddhist cave temples of Ajanta, and imitations of timberwork and joinery are also realised in the megalithic caves, although no actual timber structures of such an early period remain.

When it came to the conquerors of North India ‒ the Delhi Sultans ‒ the standing temples were objects of idolatry, but at the same time their stone elements were seen as instantly available building materials which could be taken down and reassembled into an approximation of the forms required. To demonstrate the establishment of the new power, the first act of dominance would be to demolish the towering temples, the symbol and centre of the old order, and build the place of worship for the new faith. A Muslim army’s key requirement was a place of prayer, and open areas known as namāzgāh, with a wall indicating the direction of Mecca would be set up ‒ large enough for the whole army ‒ some of which still survive. The sight of thousands of troops praying simultaneously would have been startling to the local population. The next move would be to build a mosque, as impressive, if not more so, than the standing temples. The components of these buildings ‒ built on the trabeate system based on beams resting on columns ‒ were held together not by mortar, but by the downward pressure of the weight of the stone components: all these could be used to build mosques, adopting the same system, but on a new plan. Careful reassembly on an entirely different layout resulted in decorative schemes that retained indigenous floral and geometric carved patterns, but human and divine images were defaced, or the stones turned back to front to use the plain surface, although carvings of animals were sometimes retained.

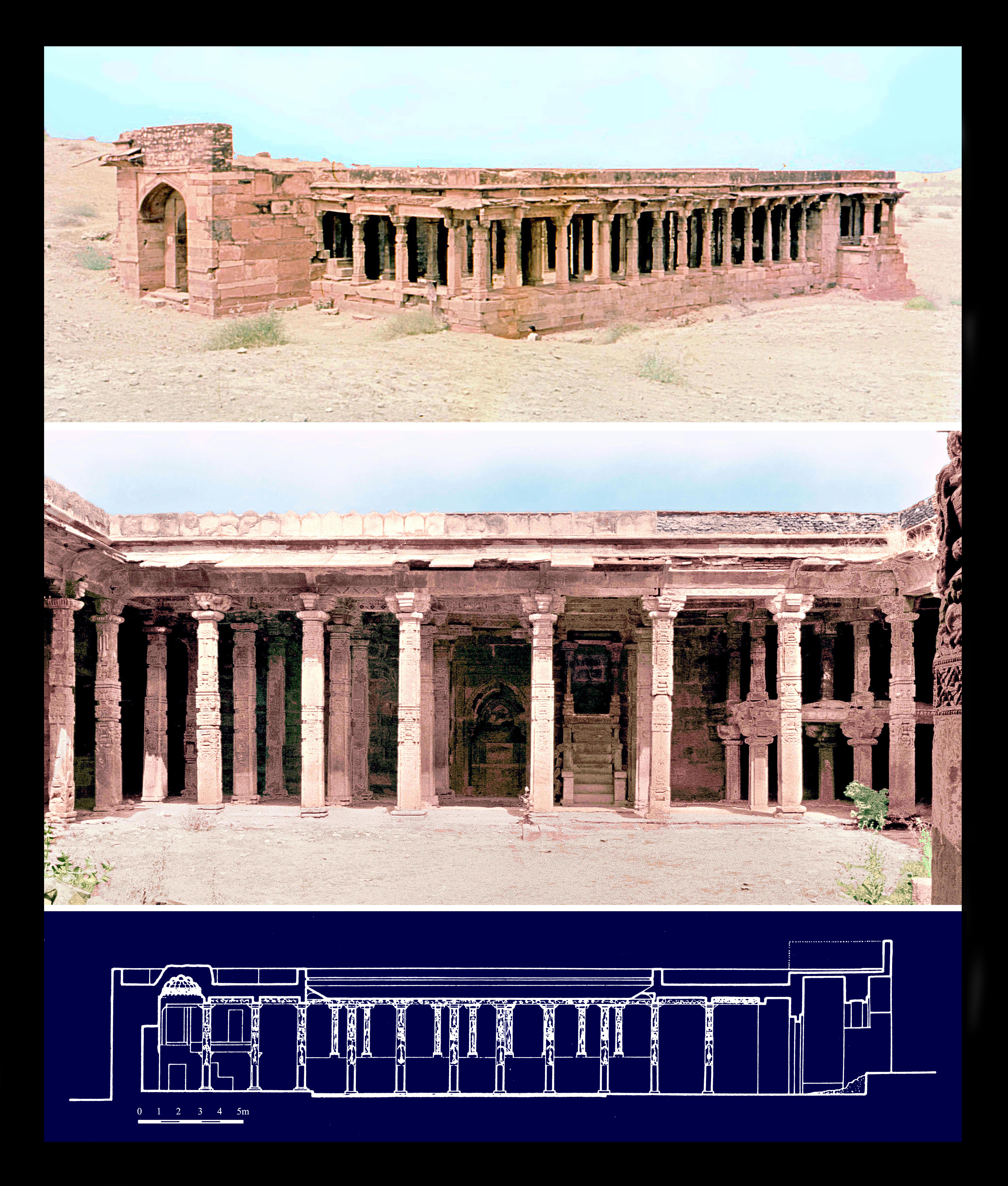

Ajmer, Rajasthan, Aṛha’i din kā Jhoṅpṛa, one of the first mosques built out

of the spoil of demolished temples by the Ghurids as a sign of conquest

in 588/1192‒3. Left: interior, three column shafts are superimposed to

create a huge lofty hall, with a roof of slabs resting on lintels combined

with reassembled corbelled domes, using the local building methods.

Right: the free-standing purpose-built screen wall added by Īltutmish

in c. 623/1225‒6 to give the mosque an outer appearance of the

vaulted ivāns of Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia, the builders’

homelands

Numerous sultanate buildings have survived in Delhi and

in North India, providing a clear picture of architectural

developments of this era. The early sultans’ destruction

of temples as a religious duty and the reuse of spolia as

an act of symbolic appropriation is demonstrated in the

mosque of Quwwat al-Islām in Delhi, built in 588/1192‒3.

To the west, in Rajasthan, the mosque known as Aṛha’i din kā Jhoṅpṛa – meaning “the hut built in two and a half days” alluding to its speedy construction – was erected the same year. Like the Delhi mosque Aṛha’i din kā Jhoṅpṛa is laid on an Arab-type plan with a vast courtyard surrounded by colonnades. The appearance of such mosques, while striking, must, however, have seemed alien to the builders, and in both cases a freestanding screen wall was added as a compromise to provide some resemblance to the vaulted ivāns and arcades of the Ghurid homelands, but still using horizontal layers of corbelled stone, rather than employing true arches.

In a temple city spectacular processions would have been the norm. A Hindu city would have the palace and temple at its core with the arrangement of the dwellings of the various castes complying to sacred diagrams, according to the hierarchy, sometimes in rings of fortified walls, which may have appeared impressive, but would trap the inhabitants if surrounded by besiegers. In a Muslim city the arrangement is pragmatic and defensive. The palace complex is within the fort, which is set at one side of the walled town. The main mosque for the Friday prayers would be in the centre of the town, linked to the palace by a processional route. Graveyards – unknown in Indian culture, where the dead were not buried, but cremated – were sited outside the walled cities and villages. The extant monuments of these newly configured Muslim cities include not only mosques, tombs, and open prayer grounds known as ʿīdgāh (or namāzgāh of an army, also used for ʿĪd and other celebrations by the whole town), but other new forms of structure such Sufi khānaqāhs, minarets and madrasas (theological colleges). The conquerors encountered mighty Hindu fortifications as well as walled cities, and the local systems for water resources. These they adapted for their own use, but in their secular buildings such as fortifications, dams, stepwells, reservoirs and canals they displayed new and radically different approaches to dealing with their needs, employing a combination of new and indigenous techniques and materials.

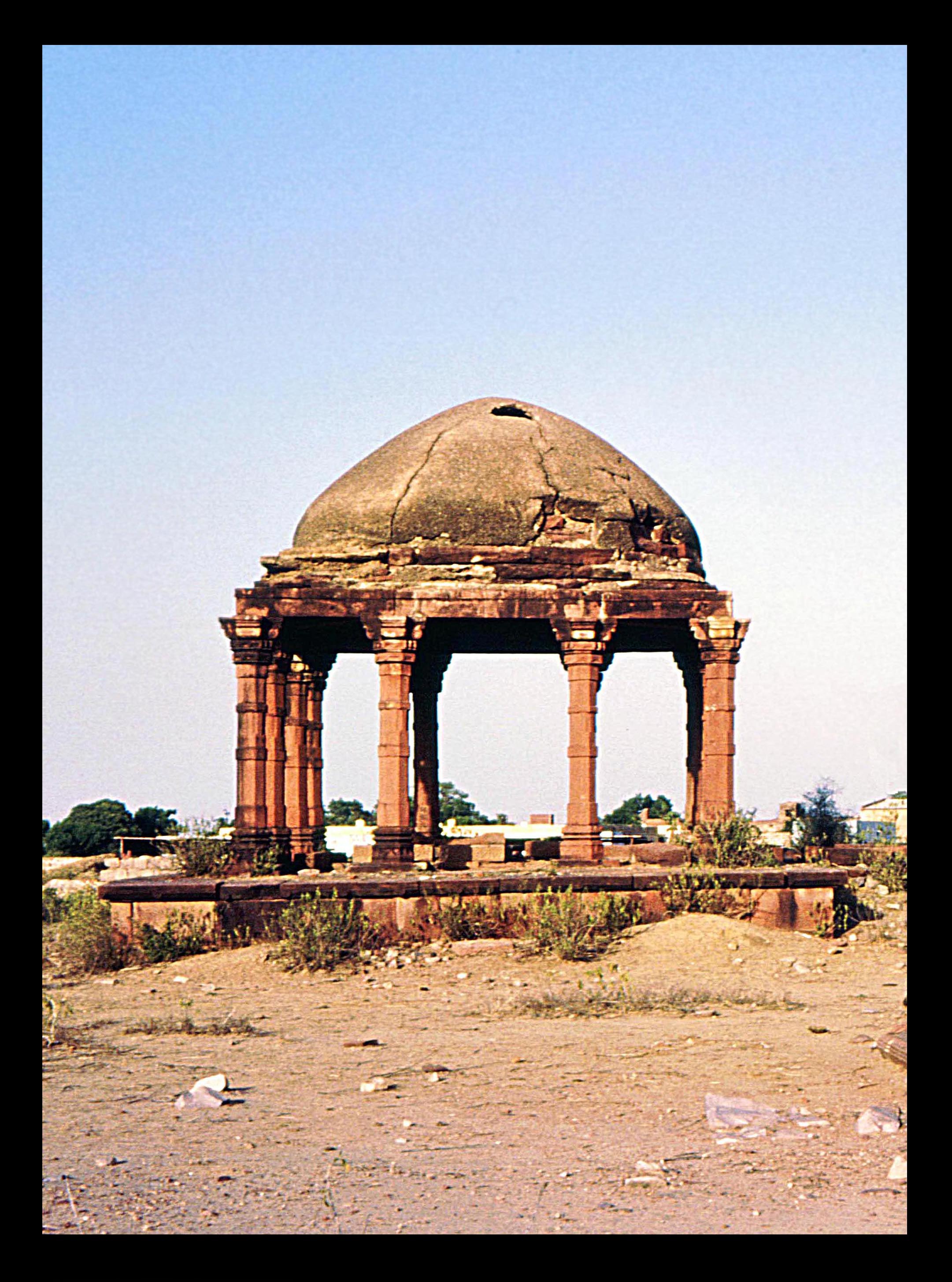

Water distribution and infrastructure were crucial for survival and prosperity, and we see examples of the ancient type of open reservoir lined with stone ‒ with steps leading down to the water table ‒ either adopted or built, An example is the Jhalār Bāʾolī of Bayana, built by Malik Kāfūr Ṣulṭānī, the governor of Bayana under Mubārak Shāh Khaljī (reg. 716‒20/1316‒20), for the use of the public and perhaps partly to serve the needs of the Khaljī army in camp, but walled against the desert environment and embellished by a shady colonnade running all around the tank, with a roof terrace and four corner pavilions accessible by stairways, all of which would have provide a pleasant retreat in the cool of the mornings and evenings. Even now in its ruinous state it provides a micro-climate and haven for indigenous and migrating birds.

The Jhalār Bāʾolī of Bayana, Rajasthan, dated 717/1318‒19 and built

as a multi-functional retreat for the population. The water is accessible

via the steps even when the water table is low in Summer, as in the

photograph. The building was vandalised in the riots at the time of

the Partition of India in 1947

The tomb of Ghiyāth al-dīn Tughluq, Tughluqabad, Delhi. The tomb

reinterprets pizé in stone: to create a monumental effect the structure

is built with large blocks of red sandstone, with a string course and

niches of white and black stone inlay. The dome, clad with marble, has

a Muslim – Persian – profile, but is surmounted with an amalaka and

kalasha, borrowed from ancient Indian architecture, adorning the temple

śikharas and maṇḍapas as finials. The fine and well-proportioned design

of the tomb contrasts with the robust appearance of the enclosure and

the towering walls of the town and fort. The delicately fringed four-

centred arches add a sense of lightness to the otherwise massive walls.

When the conqueror’s rule became established, the influx of settlers from the cultural centres of Iran and Central Asia led to a consolidation of techniques and materials, combining trabeate and arcuate styles. Features such as the pizé walls of the homeland were reinterpreted as massive battered dressed stone walls, with contrasting stone inlay and fine calligraphy designed by Muslim master craftsmen. By the time of the Tughluqs (780‒817/1320‒1414), visual demonstrations of dominance were put aside in favour of practical measures for the consolidation of power and production of wealth. The sultans built not just monuments to demonstrate their authority, but, as their predecessors had also done, whole new cities on virgin ground, but grander, better designed and with a particular eye to the climate. Outside Delhi, Ghiyāth al-dīn Tughluq (reg. 720-25/1320‒25) built – in less than the five short years before his untimely death – a new capital for himself, Tughluqabad. The city, set by an artificial lake to provide a micro-climate, included the Sultan’s tomb. The substantial stone chamber is set in its own fortified enclosure reached by a causeway across the lake. The tomb employed battered walls, not for defence, but to add to the impact of the monument.

Architecture took an entirely different turn with the invasion of Bābur (reg. 932-7/1526-30) and the establishment of the Mughal empire. A new vocabulary developed, first seen in the Tomb of Humāyūn at Delhi, with its Persian-style domes, the burial place in a crypt, and the whole set in the centre of a Persian type of garden (chahār bāgh) divided by watercourses reflecting the tomb. This type of garden, built for pleasure, usually had the pavilion at the far end. In India, for the gardens around Mughal tombs, the tomb is at the centre, except notably in the Tāj Maḥal, where the tomb is at the far end, with a view to the river Jumna and a wide expanse of gardens on the opposite bank. The emperor Akbar was greatly interested in religious debate and the unification of religious ideologies. Jesuits were invited to his court to expound their views.

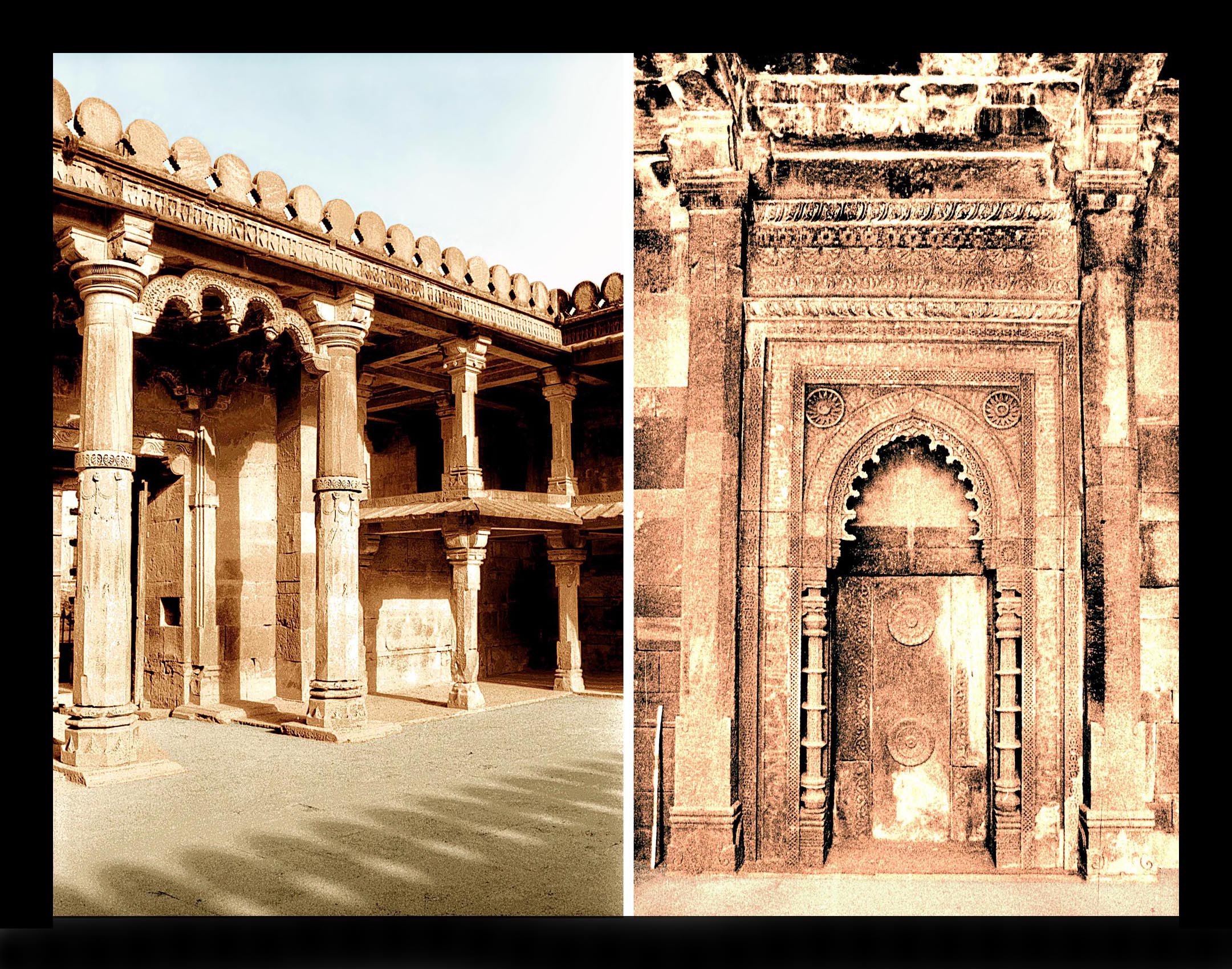

The emperor also attached importance to the Sufi Shaikh Salīm Chishtī. While a lavish dwelling would be inappropriate for a mystic teacher, the emperor was able to express his veneration by building an unparalleled mosque in the shaikh’s honour, in the new capital, Fathpur Sikri. The Mosque of Shaikh Salīm, built mainly of the finest red sandstone, exemplifies the empire’s and Akbar’s own cultural roots, the prayer hall being formed of three interconnected halls. The central one is in the Persian style, and has a triple arched opening, with a high transitional zone made of tall squinches with four-centred arched profiles supporting a Persian-style dome decorated with cartouches. The central hall opens on the north and south sides to smaller rectangular halls, constructed according to traditional Indian architecture with monolithic columns, beams and brackets supporting flat roofs, and which in turn connect with two halls, smaller than the central one, and alluding in style to Anatolian architecture: the transitional zone of the ribbed domes being supported on pendentives.

The arcade surrounding the courtyard is once again in traditional Indian style, in the idiom of the early conquest mosques, though purpose built, with tall columns and brackets supporting the slabs of the flat ceiling, but with the façades being arched. In the central chamber, the miḥrāb, inlaid with stone decoration in restrained geometric patterns, unifies the whole composition. The arcade surrounding the courtyard is once again in traditional Indian style, in the idiom of the early conquest mosques, though purpose built, with tall columns and brackets supporting the slabs of the flat ceiling, but with the façades being arched. In the central chamber, the miḥrāb, inlaid with stone decoration in restrained geometric patterns, unifies the whole composition.

Fathpur Sikri, Uttar Pradesh. The interior of the mosque built by Akbar in honour of Shaikh Salim Chishti in c. 979/1571–72. An architectural statement of empire, the interconnected prayer halls exemplify the architectural traditions of Iran, Anatolia and India itself.

The synthesis of architectural traditions continued throughout the Mughal period, and elements were adopted in Rajput architecture. Later, at the time of the British, grand public buildings still drew from the traditions laid down in Mughal and Sultanate architecture giving Indian architecture its unmistakable appearance

Muslim Epigraphy and Ornamentation: its Diversity in South Asian Culture, (Mehrdad Shokoohy)

Chapter 9 in South Asian Islam, A Spectrum of Integration and Indigenization, Nasr M. Arif and

Abbas Panakkal (eds), Routledge, Oxford – New York, 2024 pp. 187- 213 and figs. 9.1-9.16,

ISBN 978-1-032-45170-1 (Hardback), 978-1-032-57475-2 (Paperback) 978-1-003-43953-0

(e-Book)

From the day Islam was introduced to India the Muslims brought with themselves the Word, in the form of the

verses of the Quran, the Traditions of the Prophet and historical narratives. Muslims did not first arrive in India

with the sword. They came as friendly merchants bringing gold in exchange for the wonders that India could

offer ‒ from pearls and jewels to silk and fine muslin along with spices and other rarities. Welcomed by their

Hindu and Jain hosts, by the nineth century the maritime traders had established settlements, recorded by the early Muslim geographers. Their twelfth century settlement in Bhadreśvar (Bhadreshwar) on the coast of Kutch, represents what the two cultures could offer each other. While the Muslims brought with themselves the concepts of egalitarianism in their places of worship – mosques and shrines – open to all, they also brought the art of presenting the word. The mid-twelfth Muslim remains at Bhadreśvar are set close to the main Jain temple, indicating a close relationship between the two communities, although they probably lived in separate quarters. In Bhadreśwar we see some of the earliest examples of the Kufic script in India, represented in a frieze in the Shrine of Ibrahim as well as on several tombstones of the same era.

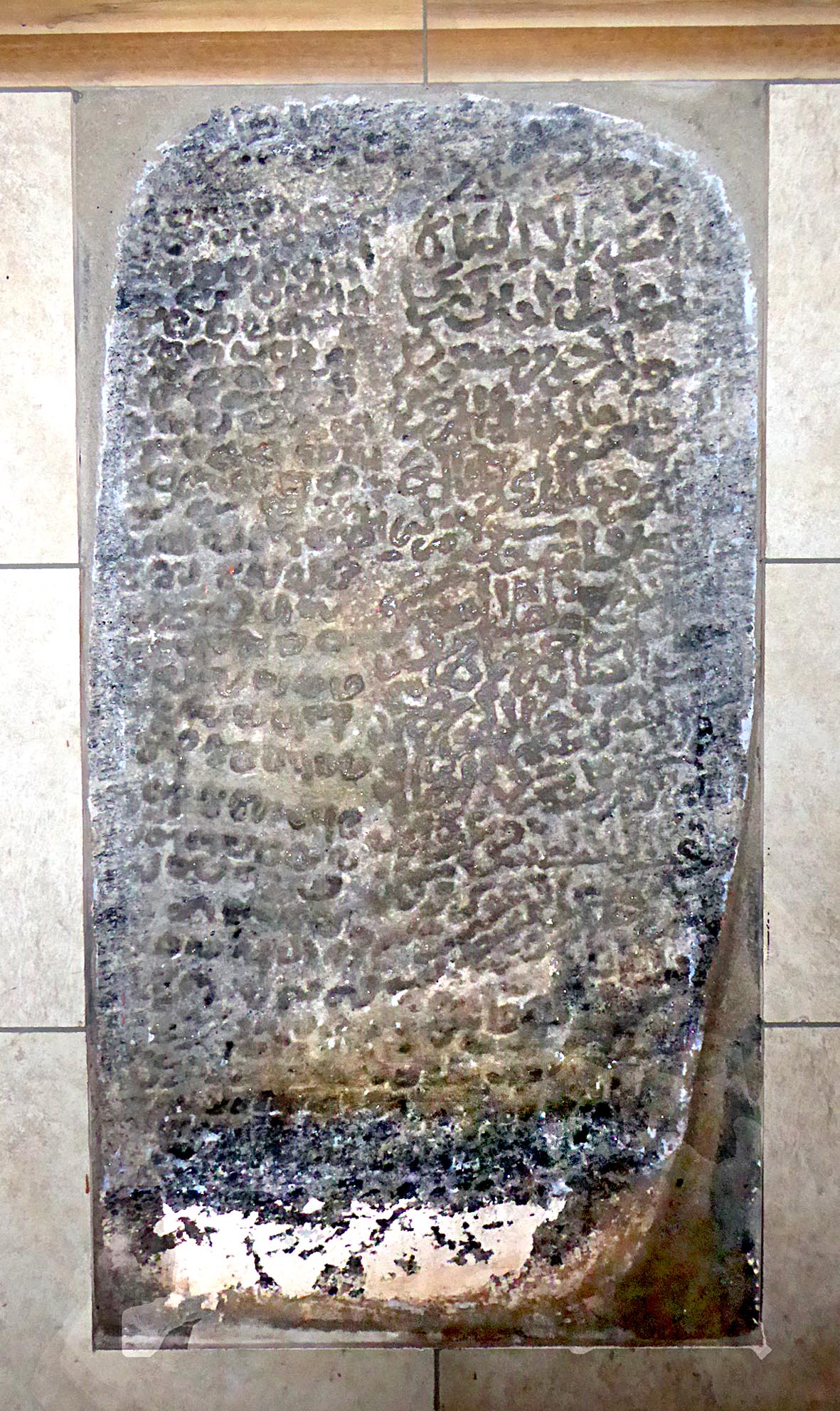

Bhadreśvar on the Gulf of Kutch, Gujarat. Above: Shrine of Ibrāhīm,

dated end of Dhi’l ḥijja 554 (11 January 1160), stone panels of the

portico, carved in the form of a wooden coffered ceiling, with a frieze

at the top of the wall bearing Quran II, 255 in a fine interlaced Kufic

script. Below: a tombstone bearing in fine Kufic a Quranic text, and

recording the death one Sumra son of Farhā[d]? in Jumādā I, 573

(October–November 1177). Only a small portion of the epitaph is

seen in the picture.

Such an integrated approach by the Muslim maritime traders was not restricted to a specific settlement but characteristic throughout the Indian littoral in subsequent periods. The merchant communities of South India incorporated Indian – religious Hindu – motifs freely in their early edifices, such as the fourteenth-century Mithqālpaḷḷi (rebuilt in 986–7/1578–9) in Calicut. An example is the vajramastaka, a common South Indian Hindu motif associated with protection from lightening, used on the eaves of the Greater Jāmiʿ mosque of Kayalpatnam (Jāmiʿ al-kabīr or Khuṭba Parriapaḷḷi), datable to 737/1336‒7, as well as on the Aḥmad Nainār Mosque, in the same town and dating from the same era, if not earlier. In this part of India the columns of the Muslim edifices adopt the elaborate details of Hindu decoration, apart from the representation of human figures. Such an integrated approach by the Muslim maritime traders was not restricted to a specific settlement but characteristic throughout the Indian littoral in subsequent periods. The merchant communities of South India incorporated Indian – religious Hindu – motifs freely in their early edifices, such as the fourteenth-century Mithqālpaḷḷi (rebuilt in 986–7/1578–9) in Calicut. An example is the vajramastaka, a common South Indian Hindu motif associated with protection from lightening, used on the eaves of the Greater Jāmiʿ mosque of Kayalpatnam (Jāmiʿ al-kabīr or Khuṭba Parriapaḷḷi), datable to 737/1336‒7, as well as on the Aḥmad Nainār Mosque, in the same town and dating from the same era, if not earlier. In this part of India the columns of the Muslim edifices adopt the elaborate details of Hindu decoration, apart from the representation of human figures.

Kayalpatnam, Tamil Nadu, Aḥmad Nainār mosque displaying the Hindu vajramastaka motif on the eaves.

To the right is a line drawing of the exterior projection of the miḥrāb, showing the same motif.

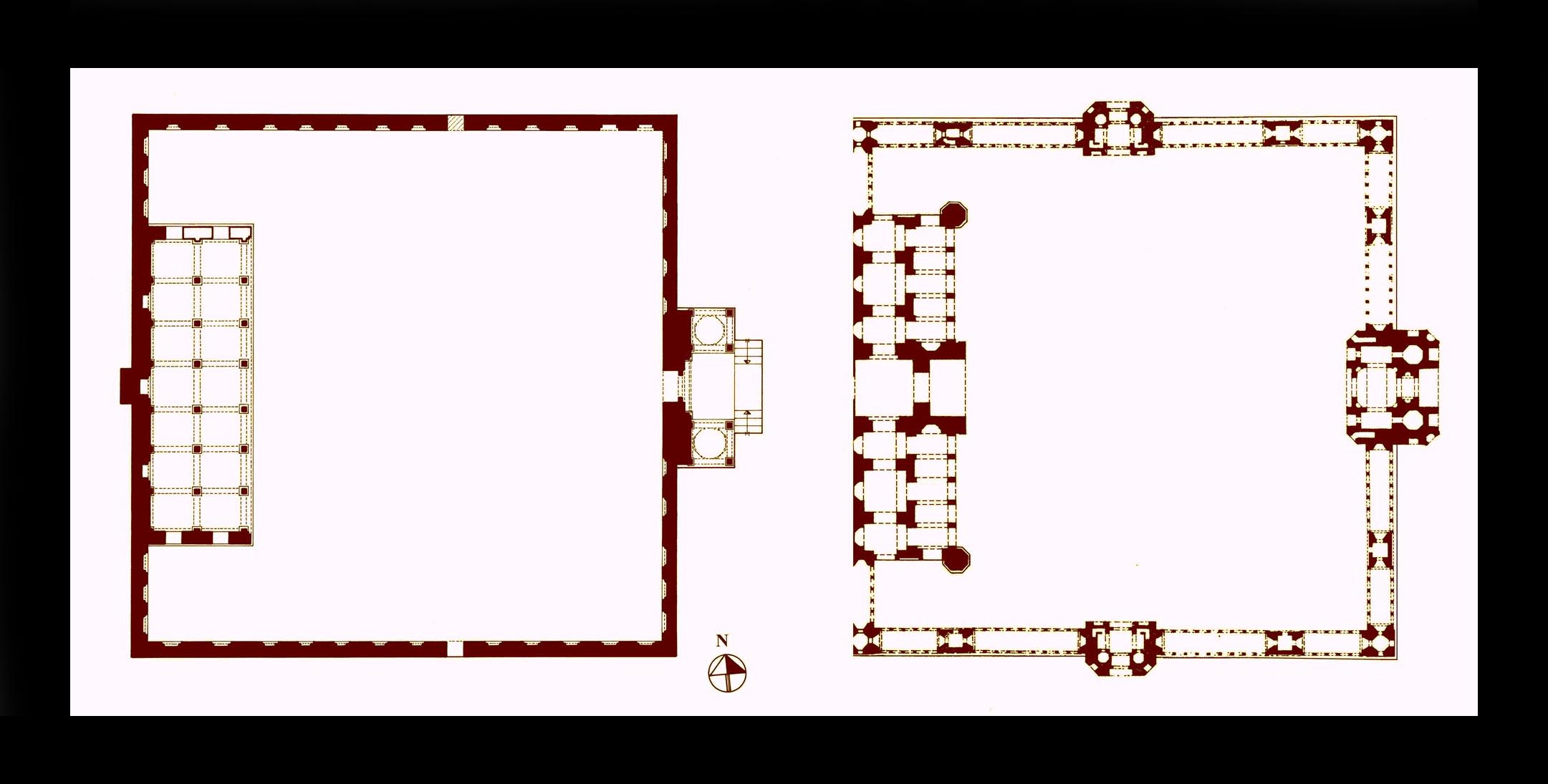

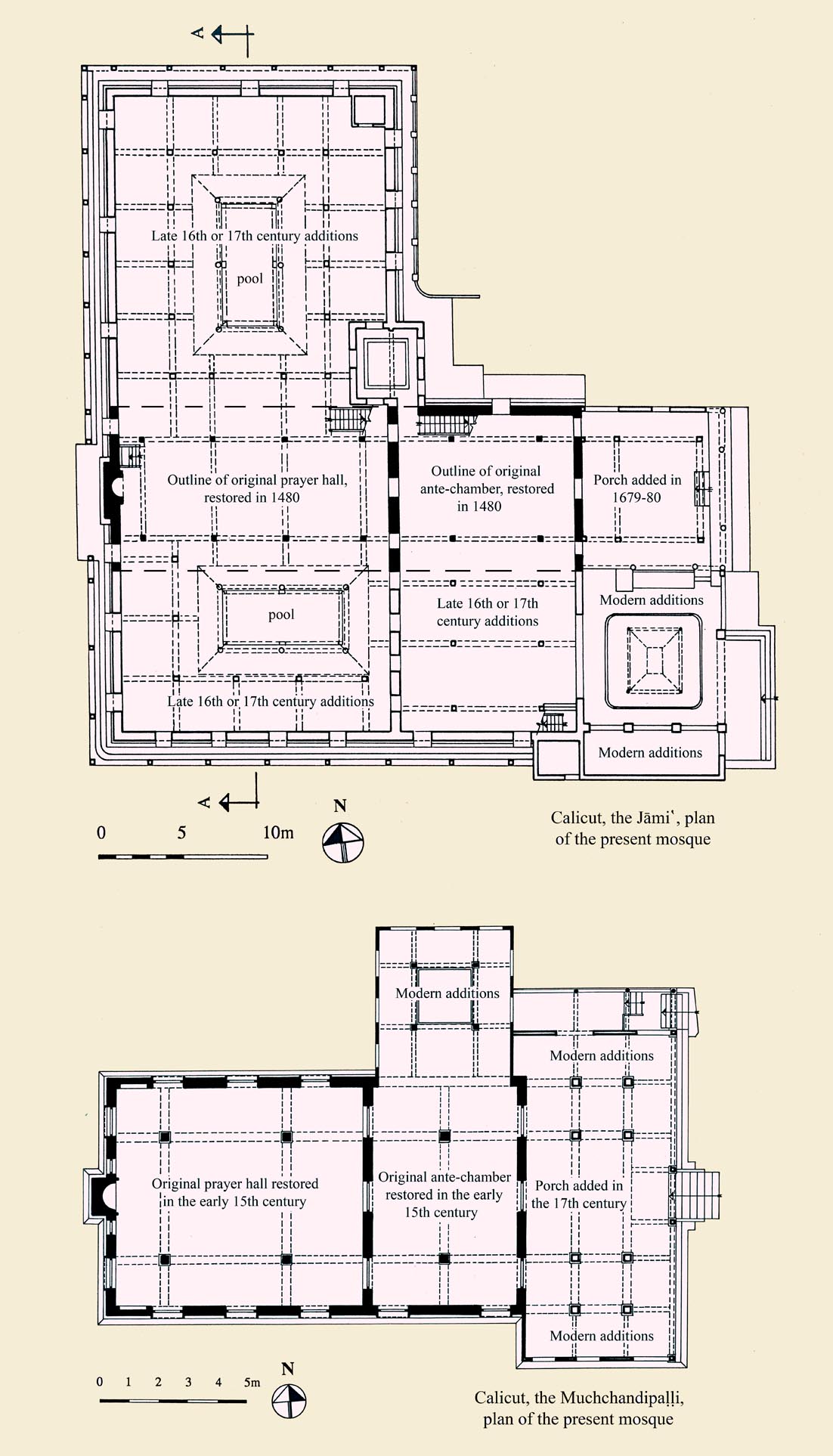

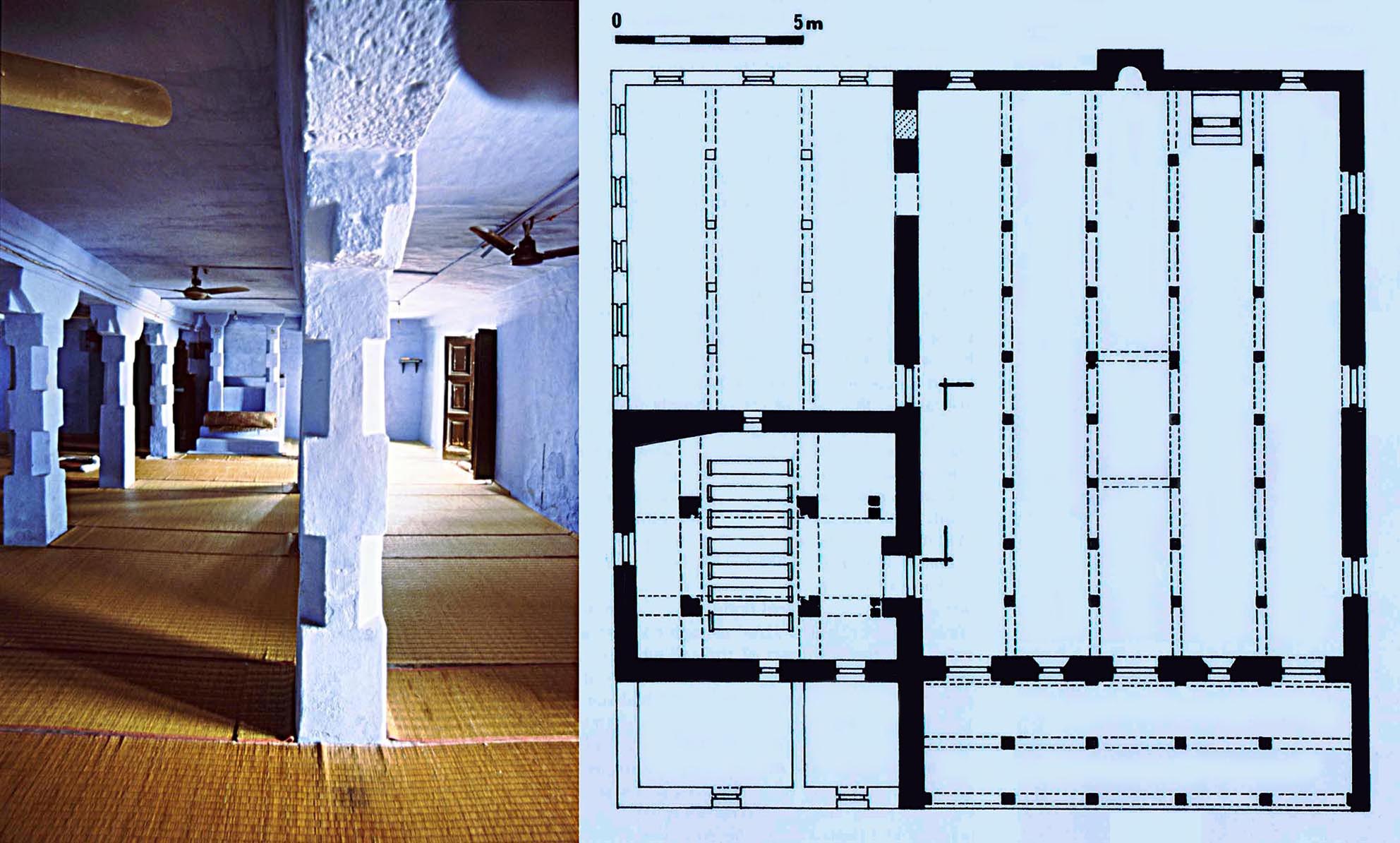

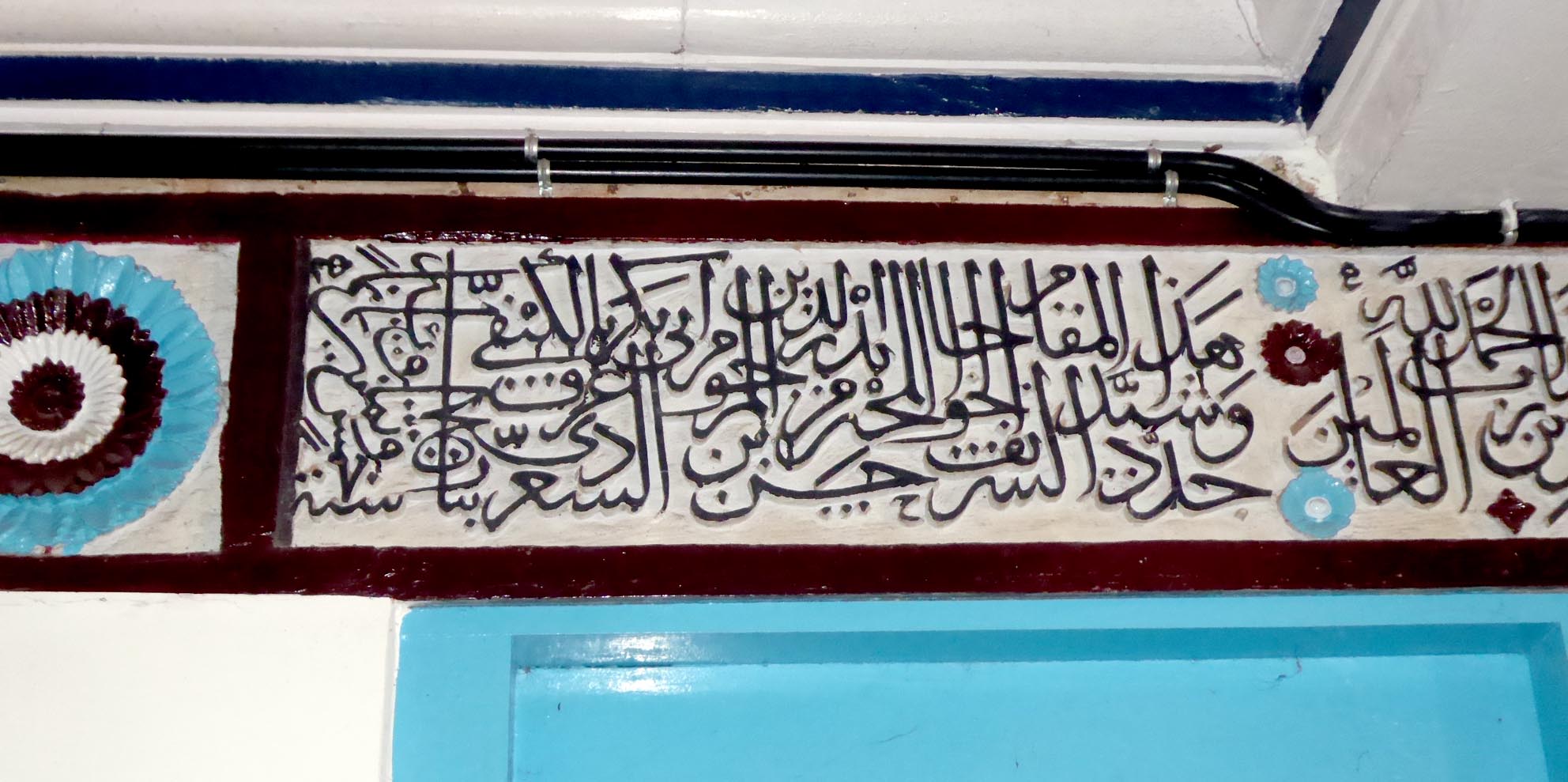

Calicut provides a good example of this synthesis. The Muchchandipaḷḷi is one of the oldest mosques to have survived the onslaught of the Portuguese and the present building dates from the fifteenth century. The additional portico in front of the entrance features an elaborate coffered ceiling supported by highly decorated beams, all carrying Quranic inscriptions, except on one of the beams which bears a historical text recording the construction of the portico by one ʿAbd’ul-Qādir ibn Ibrāhīm in the late seventeenth centuty. The inscription is in relief and the calligraphy, while not of exceptional quality, is decorated with a band of intricate carved ornamentation, typically Hindu. In the context of cultural connections the motifs are of interest in that they comply harmoniously with Muslim decorative parameters. Calicut provides a good example of this synthesis. The Muchchandipaḷḷi is one of the oldest mosques to have survived the onslaught of the Portuguese and the present building dates from the fifteenth century. The additional portico in front of the entrance features an elaborate coffered ceiling supported by highly decorated beams, all carrying Quranic inscriptions, except on one of the beams which bears a historical text recording the construction of the portico by one ʿAbd’ul-Qādir ibn Ibrāhīm in the late seventeenth centuty. The inscription is in relief and the calligraphy, while not of exceptional quality, is decorated with a band of intricate carved ornamentation, typically Hindu. In the context of cultural connections the motifs are of interest in that they comply harmoniously with Muslim decorative parameters.

Calicut, the Muchchandipaḷḷi. Above: detail of the dated

inscription of the portico of the mosque. Below: the portico’s

coffered ceiling decorated with complex lotus flowers, and below

the inscriptions a register consisting of a series of vajramastaka

patterns intermitted with smaller vajramastakas flanked by lotus

leaves. Below this register is a highly floriated wavy patten,

common in Hindu ornament. The wood of the ceiling would

originally have been oiled, or stained with subtle colours. The

brightly coloured paint is modern.

The incorporation of Hindu, Jain and even Buddhist patterns is not confined to the edifices of the Muslim maritime settlers. This assimilation is evident from the very early period of the Muslim conquest of North India. In the twelfth century the political map of Iran and Central Asia was rapidly changing with the Turkish elements rising to power and eventually ending with the Mongol conquest a century later. Such changes led to the Ghurid conquest of Delhi at the end of the twelfth century, establishing Muslim power in North India, from the Punjab to Bengal.

From the very early days the artisans were not inhibited about – or prejudiced From the very early days the artisans were not inhibited about – or prejudiced

against – learning, adopting and incorporating Hindu and Jain decorative elements

into their designs and combining them with their own. So, in the screen wall of the

Quwwat al Islām mosque in Delhi built in the late twelfth century and later extended

in the thirteenth century, in front of the prayer hall we see the combination of a well-

established traditional Muslim design with ancient Indian decorative motifs – Hindu

and Jain – not side by side, but amalgamated and well-integrated.

One would expect Muslim decorative and ornamental design to dominate, but the

Hindu traditional designs were so deeply rooted in the arts of North India that they

crept back into the architecture of Delhi. Taking the new gate built at the south of the

Quwwat al-Islām by ʿAlāʾ al-dīn Khaljī (reg. 695–715/1296–1316) we see that the

gate itself, in the form of a chamber, with three arches opening to the outside and

one leading to the courtyard of the mosque, follows traditional Muslim architectural

design of the Iranian world of the period, but executed in stone rather than brick.

However, on the face of an outer arch we see a curious pattern that may at first

seem like repetitions of a flower motif, common in Muslim designs, but when looked

at carefully manifests itself as a swastika, one of the holiest Hindu symbols, repeated

as a foliated pattern.

Delhi, Quwwat al-Islām mosque. ʿAlāʾ al dīn Khaljī’s

gate (dated 15 Shawwal 710/7 March 1311). Decorative

carvings on the pier of the arch, displaying a Hindu patten

of swastikas in the form of a field of repeating floral motifs.

The fourteenth century was a time for many innovations in North India, particularly under the patronage of Fīrūz Shāh Tughluq (reg. 752–90/1351–88), a learned man who designed buildings and cities. At this time a conscious synthesis of old Indian and Muslim art took place in architecture. A good example is the garden pavilion known as the Gūjarī Maḥal, apparently designed by Fīrūz Shāh to the north of the palace in the town of Hisar, also designed by the sultan and built under his personal supervision. While digging for the foundations of the palace some ancient Indian columns were uncovered, and Fīrūz Shāh made use of them in his royal mosque and in the garden pavilion, this time not as symbols of dominance, but simply for aesthetic reasons. On the interior of the Gūjarī Maḥal the pivotal elements are four ancient marble columns with fluted shafts, their elegant curved bases and capitals harmoniously supporting Islamic style arches and domes.

Outside the territory of Delhi sultanate, the culture of Muslim Bengal was quite different. As the furthermost north-east region of the Subcontinent, Bengal had an older tradition of its own, related to the Muslim maritime trade with South-East Asia and China. As far as the language of the Muslim inscriptions is concerned, in South India – Kerala and Tamil Nadu – the inscriptions, both religious and historic, are in Arabic. On the other, hand in the north, including the regions of Delhi, Rajasthan, Gujarat, and as far south as the Deccan, as well as in Pakistan, the historic epigraphs are in Persian, while Arabic is reserved for quotations from the Quran and the Traditions of the Prophet (ḥadīth). In Bengal too the language of the ruling sultans was Persian, but many of their historic inscriptions are in Arabic. Persian became widespread only after the Mughals took over the region. The calligraphy of the Bengal sultanate is also different from that of the other regions, being mostly in the form of an interlaced thulth with elongated strokes for letters such as alif (a), lām (l) and kāf (k). Outside the territory of Delhi sultanate, the culture of Muslim Bengal was quite different. As the furthermost north-east region of the Subcontinent, Bengal had an older tradition of its own, related to the Muslim maritime trade with South-East Asia and China. As far as the language of the Muslim inscriptions is concerned, in South India – Kerala and Tamil Nadu – the inscriptions, both religious and historic, are in Arabic. On the other, hand in the north, including the regions of Delhi, Rajasthan, Gujarat, and as far south as the Deccan, as well as in Pakistan, the historic epigraphs are in Persian, while Arabic is reserved for quotations from the Quran and the Traditions of the Prophet (ḥadīth). In Bengal too the language of the ruling sultans was Persian, but many of their historic inscriptions are in Arabic. Persian became widespread only after the Mughals took over the region. The calligraphy of the Bengal sultanate is also different from that of the other regions, being mostly in the form of an interlaced thulth with elongated strokes for letters such as alif (a), lām (l) and kāf (k).

Gaur, the site of the old capital of Bengal. Above: inscription of

Shams al-dīn Yūsuf Shāh (reg. 879‒866/1474‒81) not in situ

but now fixed on the gate of the Qadam Rasūl mosque and

recording in Arabic the construction of a mosque in 885/1480‒1.

The only Persian word, pādshāh (king) is Arabized and the

Persian letter p is substituted with the letter b. The epigraph

is in thulth, with elongated letters interlaced with horizontal

strokes of the letter kāf, and large-sized letter nūn (n). The

style of the inscription is characteristic of most of the pre-Mughal

inscriptions of Bengal. Below: Tantīpara Mosque (c. 1480). The

decoration of the arch of the central entrance, formed with

moulded bricks decorated with interlacing vines with rosettes,

is perhaps an expression of the Hindu concept of the Tree of

Life, but represented almost like patterns.

The inscriptions of Bengal are not meant to be decorative, but simply informative. Nevertheless, ornamental features can be seen in many of the edifices in the form of glazed tiles and moulded brick. Bengal, formed by the estuary of the Ganges, is rich in clay and the tradition of brick construction goes back to the Buddhist era. Decorative tilework in Bengal is not sophisticated, as in the fourteenth to fifteenth century Deccan or in Multan, but can be found in many buildings of Gaur. However, ornamental moulded bricks are widespread and can be seen on the exterior of the buildings for the corner towers and on the spandrels of arches as well as on the interior mainly on the miḥrābs and other niches. A good example is in the Tantipara Mosque depicting vine decoration and rosettes, but alluding to the Hindu concept of the Tree of Life.

The assimilation of all aspects of the Indo-Muslim visual arts with older The assimilation of all aspects of the Indo-Muslim visual arts with older

indigenous traditions is perhaps best seen in Gujarat. The Gujarat architects,

artisans and stone carvers incorporated the Jain and Hindu repertoire fully

into their designs. The amalgamation of the Muslim and Indian traditions

continued in the region unabated even after its conquest of the region at the

end of the thirteenth century by the sultanate of Delhi and later under the

independent Sultanate of Gujarat. Building out of temple spoil – exercised

formerly in North India as a sign of dominance – in Gujarat gave way to

constructing buildings in the same manner, but purposely designed,

employing traditional Indian motifs: the patterns of diamonds, lotus and

lotus leaves, serpentine scrolling patterns, miniature bas-reliefs of temples

and numerous other configurations. A good example is the depiction of the

design of the Tree of Life. We have noted an allusion to it in the arts of other

regions, particularly Bengal, but in Gujarat it appears first in the traditional

Indian form in the early mosques of the Sultanate of Gujarat, in the Grand

Jāmiʿ of Ahmadabad built in 826/1423.

Hindu motifs embellish all sultanate buildings of Gujarat, including the

sophisticated reservoirs such as Adalaj Wāv, a structure built in VE 1558/

1502 AD under the patronage of Sultan Maḥmūd Baigara (reg. 863‒917/

1458–1511) for the use of his Hindu subjects. In this reservoir we see not

only diamond patterns, hanging drops and rows of downward turned semi-

circular lotus patterns with a border of pearls, common in almost all

temples; above them are representations of a row of miniaturised North

Indian temple towers (śikhara). The Adalaj Wāv is not the only structure

built under the Muslim sultans for the majority population. The sultans

allowed their courtiers to patronise the construction of temples, reservoirs

and other Hindu or Jain edifices.

Ahmadabad. Above: Sīdī Saʿīd or Sīdī Sayyid’s Mosque, pierced stone window depicting the Tree of

Life in a design with pure Muslim antecedents that might be found as a pattern for a textile or

carpet. The carving is exquisite and the dark silhouette of the pierced stonework of the window

creates a fascinating play of light and shade in the interior of the mosque. Below: Adalaj Wāv, a

reservoir built by the permission of Sultan Maḥmūd Baigara for the use of his Hindu subjects and

adorned with Hindu ornamentation. Details of the balustrade of the underground platform.

In the late fifteenth and sixteenth century, the Muslim concepts of ornamentation gained strength gradually and familiar Muslim floral patterns began to appear in the carved decoration. From the early days of the Gujarat sultanate Muslim-style foliation can be found in the tombs of the wives of Aḥmad Shāh (reg. 813‒46/1410‒42), but later, foliation and floral motifs as well as Islamic geometric patterns appeared on many buildings. Most intriguing is the development of the representation of the Tree of Life. It began to lose the rigidity of the Hindu standard pattern, and became more realistic and foliated in design, as appears in many mosques and shrines. The tree eventually appears in its pure Islamic form on the pierced stone screens of the mosque of Sīdī Saʿīd (or Sīdī Sayyid). This mosque built in 978/1570‒1 is one of the latest edifices of the Sultanate period before the Mughal takeover of Gujarat.

Muslim art took a new turn in the sixteenth century when the Mughals invaded, creating a vast empire in North India, also wielding nominal power over the sultanates of the Deccan. Much has been written about Mughal art and their architectural heritage attracts visitors from all over the world. The Mughal inscriptions take many forms; apart from carving in relief they also created a large number of inscriptions in the form of inlay, often with coloured stone set in marble. This type of inscription was almost as long-lasting as those carved in relief, but created a smooth surface on the walls. They went even further, and, on the interiors, created inscriptions painted on the walls, often in gold, set within highly ornamented cartouches and other decoration. Their wall painting and inlay work merges together creating exquisite results. While the Persian influence was developing strong roots in the inscriptions and ornamentation of Mughal architecture, the technology of carving and inlay, particularly in marble, was Indian, even if not of ancient or Hindu origin. The best manifestation of it appears in the tomb of Iʿtimād al-daula, the Persian father-in-law of the Emperor Jahāngīr (reg. 1014–37/1605–27). As long as Iʿtimād al-daula was alive he virtually ran the Empire and when he died, his daughter, Nūr Jahān, the beloved wife of the Emperor, built a mausoleum for her father which is enriched on the exterior with marble inlay decorated entirely with Persian patterns similar to those which appear in Iranian wall paintings.

Mughal inscriptions and ornamentation at their zenith, during the reign of Shāh Jahān. Left: the lower shaft of a marble column and its base in the audience hall of the Emperor’s palace in the fort of Agra. The inlay is coloured stone as well as precious and semi-precious stones, creating a subtle, colourful and harmonious design. The small red stones are garnets and the light blue stone on the top of the centre of the base is turquoise. Other gemstones are also employed, including lapis lazuli. Right: view of one of the public rooms of Shāh Jahān’s palace in the Red Fort at Delhi. The flowing arabesque designs are similar to those seen in Agra, and derive from Persian ornamentation, but the lobed arches are characteristic of later Mughal architecture. In a cartouche above the arch is the first stanza of a Persian verse, with the other over the next arch not in the photograph, declaring: “If paradise could be on earth, it is this, it is this, it is this”. The inscription and many others of the period are in fine nastaʿlīq.

Agra, the Taj Mahal, the mausoleum built by Shāh Jahān for his beloved queen and himself. Two panels Agra, the Taj Mahal, the mausoleum built by Shāh Jahān for his beloved queen and himself. Two panels

decorated with flowering shrubs are apparently taken from similar European patterns, but executed in

different materials. Above: detail from the mausoleum itself, with the plants carved in fine low relief in marble.

Below: a similar design rendered in red sandstone for the mosque of the complex. The deep shade of the

courser material contrasts with that of the tomb to set it to advantage. The panel from the mausoleum is

bordered by an interlaced floral pattern inlaid in the same manner as those seen in the palaces of Shah Jahān

while that of the mosque has a simple geometric zigzag border, as found in many earlier monuments.

A generation later, at the time of the Emperor Shāh Jahān (reg. 1038–68/1628–57) a

more subtle style of decoration developed which although it still had references to

Iran, was entirely Indian. Inlaid marble continued to be favoured, often incorporating

precious and semi-precious stones. The appearance was richer and grander than

anything seen before, but simpler in general design. At the same time, in the palaces

of Shāh Jahān, wall-painting and even painting of the ceilings became more elaborate,

often incorporating gilding. From the early days of the Mughals the Portuguese had

opened trade routes to India, South-East Asia and China, establishing small enclaves

as their territories all along the Indian Ocean coasts. The Portuguese found friendly

relations with the Mughal court expedient, and accepted, at least nominally, Mughal

dominance. This relationship resulted in a flood of European artifacts, engravings,

prints and drawings finding their way to the Mughal court and into the hands of the nobility. The effect of all this new material on Mughal art was great, and is seen particularly in later Mughal miniatures. Stone carvers and artisans were also influenced by the European images, for example in the depiction of flowering shrubs, which up to then had only been rendered in the Persian style. Delicately executed examples appear in the Taj Mahal, in the mausoleum itself as well as its associated structures.

India, throughout its history, has offered much to world culture, but has also been, and is still is, a melting pot of cultures. It has absorbed elements from civilizations beyond its boundaries – Arab, Persian and European – and integrated them into its own identity. To illustrate this, one should perhaps glance at the many details in the designs by Lutyens and Baker for the Secretariat at New Delhi, proudly displaying European, Hindu and Muslim elements – complete with Persian inscriptions – not side by side or in parallel, but in an amalgamation denoting the unification of diverse cultures.

Nagaur, Muslim history and art and architecture, EI3, Part 3, 2022, pp. 114-123, illustration 1-5

Nagaur, the Buland Darwāza of the Khānaqāh al-Tārikīn (733/1332-3),

view of the gateway from the south-west, outside the enclosure. The

simple tomb of Shaykh Ḥamīd al-dīn Chishtī is within the enclosure.

Nagaur in the desert terrain of Central Rajasthan is associated with its celebrated townsman, Abū’l-Faḍl b. Mubārak, the author of the Āʾīn-i Akbarī and the Akbar-nāma, and also for its Sufi shaykhs of the Chishtī, Qādirī and Suhrawardī sects. Nagaur itself was one of the oldest Muslim strongholds in India, and its district included a number of historic towns such as Didwana, Khatu, Ladnun and Naraina, all preserving numerous sultanate monuments from the thirteenth century to the time of the establishment of the Mughal empire in the sixteenth century and displaying a distinctive local architectural style. Nagaur fort also retains later palaces of the Rajput period embellished with wall-paintings.

The foundation of Nagaur goes back to the Ghaznavids, its fort being built by Muḥammad Bāhalīm (or Bahlīm), Multan’s Governor under Bahrām Shāh (1117-57). With the fall of the Ghaznavids Nagaur fell into the hands of the local Rajputs, but the Ghurid Muḥammad b. Sām (r. 1173-1206) took over the region in 588/1192-3, and his control was consolidated in 592/1195-6 by his commander (later Sultan) Quṭb al-dīn Aibak.

.

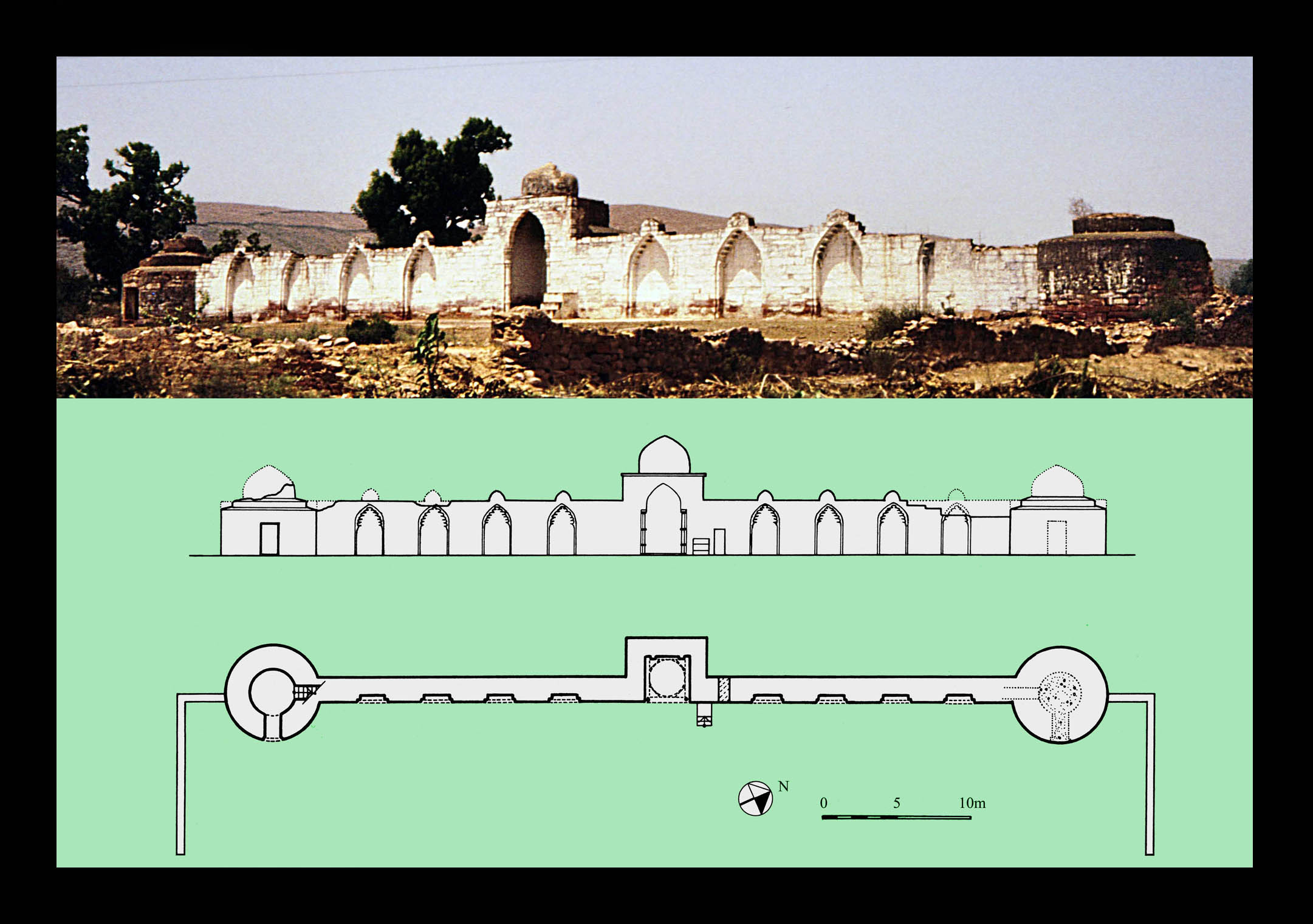

Nagaur, The early fifteenth century Shams Khān Masjid,

eastern façade of the prayer hall. Below: plan.

After Tīmūr’s sack of Delhi in 801/1398-9 the sultanate of North India disintegrated and in Nagaur an independent dynasty was established which was related by blood to the sultans of Gujarat. The founder of the independent state was Shams Khān whose dynasty lasted for over 120 years. The khans minted coins without acknowledging Delhi, although their coins have not been uncovered. Their independence is also confirmed by their inscriptions which do not acknowledge any sovereign sultan. During their reign in addition to the Sufi schools, a community of learned Jains flourished in Nagaur, leaving many manuscripts acknowledging the khans as sovereigns.

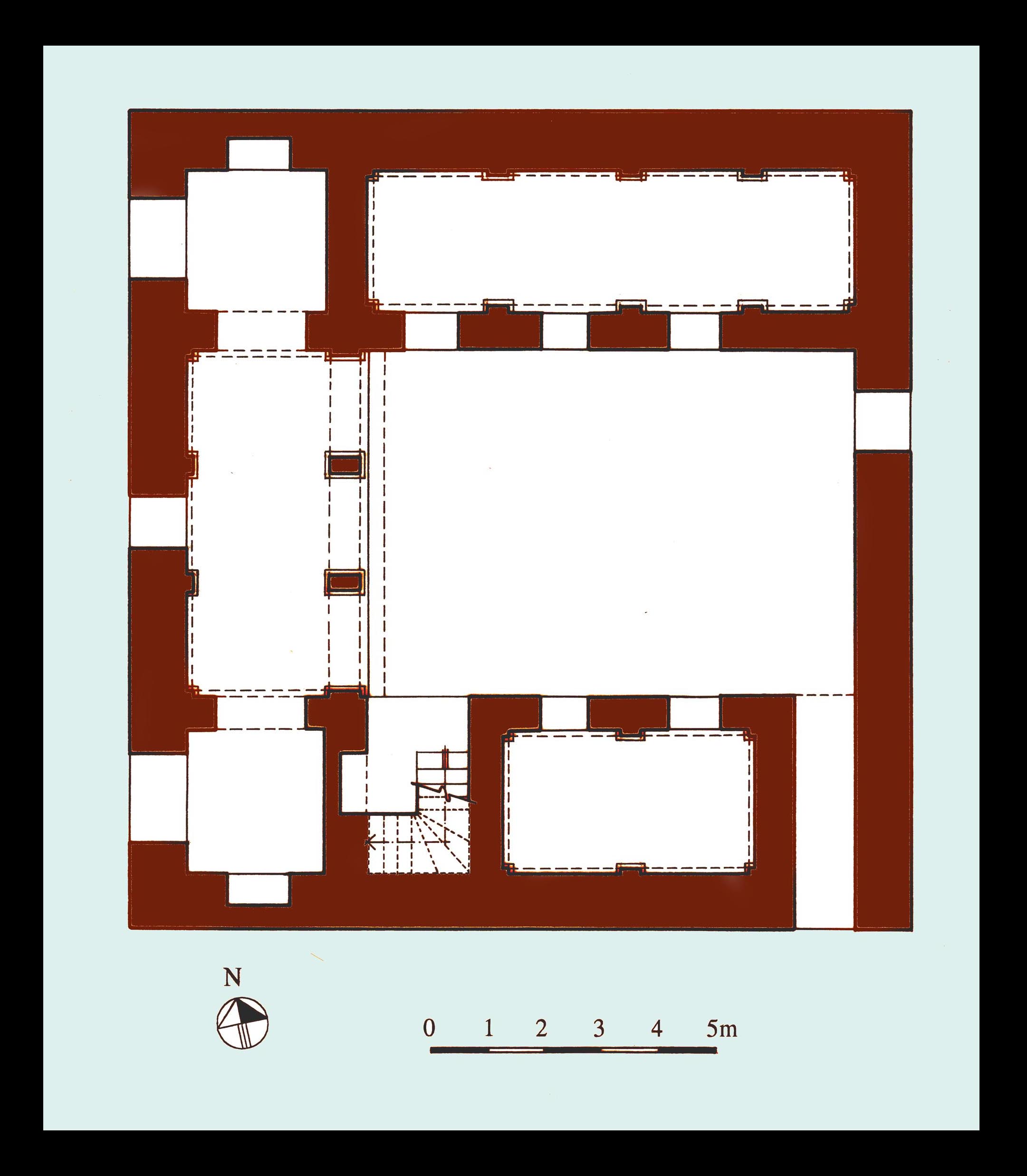

Tīn Darwāza of Nagaur, southern façade from the

middle of the central square (Ghandi Chowk). Below, plan.

An outstanding monument, and a landmark of Nagaur town, is the Buland Darwāza, the gate to the Khānaqāh al-Tarikīn, constructed during the reign of Muḥammad b. Tughluq in 733/1333; an arched portal of red sandstone,12 m. high, and flanked by two three-tiered square pavilions (chatrīs) each topped with a hemispherical dome. Two more pavilions are set on either side of the roof. Behind the portal, three chambers were added later, probably by the efforts of Makhdūm Ḥusain Chishtī (d. 901/1495-6) who took on the mantle of the khānaqāh in 859/1454-5.

The other landmark is the Shams Khān Masjid, the old Jāmiʿ of Nagaur, and a paradigm of the architecture of the independent khans. The style is an amalgam of Delhi and Gujarat. Built on the bank of a substantial reservoir, also known to be the work of Shams Khān, the prayer hall is massively built with five arches opening to large interconnected domed units. The central dome is raised over squat columns in the Gujarat style, but all domes are true domes as opposed to the corbelled domes of Gujarat.

In competition with their cousins, the Sultans of Gujarat, the khans remodelled Nagaur to resemble the Gujarat capital Ahmadabad (founded in 813/1410-11), complete with a royal square in front of the entrance of the fort with their own version of Ahmadabad’s ceremonial gate: the Tīn Darwāza. Nagaur, lacking the resources of Gujarat, made the khan’s attempts a pale imitation of the grand Gujarati architecture, but are perhaps best represented in Nagaur’s Tīn Darwāza. It consists of three archways, built with dressed sandstone with similar façades on both sides, but plastered over later. Each pier is decorated with a small arched balcony, making four on each façade, roofed with a domed profile similar to the form of a Hindu śikhāra. Above the central arch at the roof level on each side were stone balconies which are now lost. In spite of the general resemblance of the Tīn Darwāzas of the two towns, they differ in plan and in the treatment of the elevations. Apart from plainer façades at Nagaur a distinct difference is its Delhi-style four-cantered arches as opposed to almost two-centred arches at Ahmadabad.

Nagaur Fort, wall paintings in the Rajput palace, depicting carefree courtly recreations.

The combined North Indian and Gujarati style of architecture continued up to the mid-sixteenth century, but in time many of the distinctive Gujarati features, such as the imposts of domes being raised above the level of the roof, gave way to more traditional North Indian forms, and in particular the flat roofed colonnade.

During the Mughal period, Nagaur and its region fell in the hands of the Jhodpur rajas who accepted the soverign of the Mughal emperor and in the fort of Nagaur built palaces in the Mughal style, which have survived and been restored in recent years. The fort and its palaces are still the property of the Raja of Jhodpur.

South Asia, Chapter 5.2 in The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Archaeology, Bethany J. Walker, Timothy Insoll and Corisande Fenwick (eds), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2020, pp. 543–573, figs 5.2.1–5.2.8

ISBN 978-0-199-98787-0 (hardback) ISBN 978-0-197-50787-2 (epub)

From the early days of European encounters with Indian culture, merchants, travelers and officials arriving in

India were astounded at the quantity of ancient remains, dominated by Hindu and Buddhist monuments, in every

state of repair: from richly endowed temples to picturesque ruins swallowed by jungle and enigmatic mounds

hinting at past civilizations. The Muslim presence in India goes back the first century of the Hijra, but their

monuments, as with those of the host communities, would be cared for mainly because of their religious rather

than their historic significance.

Formal archaeological studies in South Asia may be taken to have started in 1870 when the Archaeological

Survey of India (ASI) was established with Alexander Cunningham (1814–93) appointed as Director, but interest

in archaeology goes back much earlier. The value of the historic monuments and vast ruins was understood and

early in the nineteenth century two legislations – the Bengal Regulation of 1810 (Regulation 19:1-3) and the

Madras Regulation of 1817 (Regulation 7) – were designed to prevent vandalism, but with little effect as the East

India Company had only nominal authority over the Subcontinent.

Although at the beginning a scholarly approach to archaeology was lacking, what attracted enlightened officials of the East India Company was the Buddhist and Hindu monuments, ancient inscriptions and numismatics. They presented papers to the Asiatic Society of Bengal, published in its Journal. Islamic sites and monuments attracted less attention as they were ubiqitous and “too recent”. We come across papers regarding Muslim materials very occasionally, such as one on eight early Muslim silver coins published in 1851, two of which date from AH 121/738-9 and 162/778-9. Although at the time the archaeology of Sind and Multan was unknown, these two early Caliphate coins pointed to an Arab presence in Sind, and over a century later explorations of the historic Arab settlements enhanced our understanding of early Muslim architecture and urban form in South Asia. Delhi was, of course, the centre of Muslim power and its antiquities were described first in 1846, not in English, but in Urdu by Sayyid Ahmad Khan (1817-98).

However, the quality and characteristics of Indo-Muslim edifices were considered before this by James Fergusson (1808-1886), a Scottish architect who plied the subcontinent between 1834 and 1845 making measured drawings of the buildings. In 1876 he eventually published his History of Indian and Eastern Architecture which, while mainly concerned with Hindu and Buddhist antiquities, included survey plans of the then unexcavated Quwwat al-Islām mosque and the tomb attributed to Īltutmish in Delhi, Shīr Shāh’s tomb at Sasaram, the Ādīna Mosque at Pandua, the Jāmiʽs of Jaunpur and Ahmadabad and the mosque called Aṛha’i din kā Jhoṅpṛa in Ajmer. He also produced a sketch of the eleventh-century minaret at Ghazna, the upper tier of which has since fallen, making his sketch our only record of its design.

In 1870 the Indian Central Government established the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), with the fifty-seven year old General Cunningham as Director. He and his few assistants explored the antiquities of various regions, publishing their reports in 23 annual volumes, each supported by sketches, measured drawings and renderings of inscriptions. The quality of the reports varies greatly. Those of Cunningham himself, while not entirely free of error, are more reliable but those of his assistants are often unprofessional, inadequate, inaccurate, and full of statements and anecdotes gathered from local pundits, presented as historical fact. An example is the report by Archibald C. L. Carlleyle (1831-97) on the town and fort of Bayana. The town was established by the Muslims in the first decade after the Ghurid conquest, yet Carlleyle devotes most of his report to the pre-Islamic fictional history, inventing a name for the town: “Bāṅāsur” and another for the fort: “Santipūr”. He ignored many of the Muslim remains, designated the Jāmiʽ mosque of the fort as a “temple converted to mosque” and described one of the most significant early conquest mosques as a temple. He gave an inaccurate sketch of the minaret of Dāwūd Khān in the fort. The shortcomings of this report were to the extent that Cunningham had to revisit the site and provide a fresh report correcting many of Carlleyle’s slips. With all their shortcomings, however, Cunningham and his assistants did set up the basis of systematic archaeological exploration, with a fair proportion devoted to the Muslim period. Nevertheless, their reports were regarded as unscientific and were criticised harshly at the time. In 1887 Sir F. S. Growse, the founder of the Mathura archaeological museum, publicly commented “The unrevised lucubrations of General Cunningham’s assistants are a tissue of trivial narrative and the crudest theories”, and the Quarterly Review of July 1889 noted "We trust that all future Reports issued by the Archaeological Department of the Government of India will be free from the defects which mar the usefulness and impair the authority of Sir Alexander Cunningham's Series”. For all that, Cunningham’s publications brought the extent and importance of Indian antiquities to the attention of the authorities.

The subsequent history of the ASI was not without ups and downs, but survived the test of time. The quality of its publications improved, reaching a zenith when the Viceroy, Lord Curzon (1859-1925), reformed the ASI, appointing a young archaeologist, John Marshal (1876-1958). Under his directorship the work of the ASI reached a highly profesional level and numerous volumes of exploration and excavation reports were produced. The inscriptions, in Sanskrit, as well as Arabic and Persian were also studied systematically. The ASI continues its work, its many directors of different calliber being appointed directly by the Central Government. The ASI is also responsible for the preservation, maintenance and repeair of sites and monuments. After Partition in 1947, while the ASI remained in charge of archaeology in India, in Pakistan and subsequently Bangladesh similar offices were established with their own archaeological departments.

Major Sites and Edifices

Eighth to early twelfth century

The Arab appearance on the coasts of India goes back to pre-Islamic times and large numbers of Roman, Byzantine and early Muslim gold coins found in India were brought via the Red Sea by the maritime traders from Syria, Iraq and elsewhere. Histories tell us that at the time of the Caliph Al-Walīd, when the Muslim ships were attacked by Indian pirates, in retaliation Muḥammad b. Qāsim took an army to Sind and first took over Daibul in 93/711-12 and within a year annexed Sind to the Caliphate. Excavations at the site of the port of Daibul at Banbhore have uncovered the perimeter of the walled town, small parts of the palace area and foundations of the main mosque with its inscription dated 109 /727-8), which makes the building one of the earliest known mosques in the world. The foundations reveal that the mosque had an Arab type plan with the usual colonnade around a central courtyard, but little survives to reveal the features of the superstructure. Further north, the village of Brahmanābād is the site of al-Manṣūra, the Arab capital of Sind, once a sizable city which is still left practically unexcavated, except the foundations of a large mosque (described by some as the Jāmiʽ) and a smaller one, both built of brick, the main building material in Sind and Multan. The excavated mosque seems to have been a walled prayer hall with a single entrance to a courtyard in the eastern side. Again, the superstructure is lost, but inside the prayer hall are the foundations of massive piers that may have supported an arcaded roof, or as some traces suggest, over each of these large piers two wooden columns probably supported a light roof.

Early in the eleventh century Multan and Swāt, to its north-east, were annexed to the Ghaznavid territory and excavations at Swāt have revealed a sizable Ghaznavid mosque, several times renovated, with stone walls and traces of wooden columns. The entire mosque was roofed and it seems that it did not have a courtyard – at least in its final form. Multan and the nearby town of Ucch retain other remains, almost all constructed of brick and many displaying glazed tilework, a reflection of the region’s association with Greater Khurāsān rather than South Asia. The oldest, the tomb of Shāh Yūsuf Gardizī (1152), has an unusual layout and structure for the region: oblong in plan and not domed. Other tombs, such as the tombs of Shāh Bahā’ al-Ḥaqq (d. 1262), Shams al-dīn Tabrīzī (d. 1276), Shādnā Shahīd (d. 1270) and Rukn-i ‘Ālam, are all built with battered walls reflecting the traditional mud-brick and pisé structures of Afghanistan.

Early Muslim geographers record many ports on the coasts of Gujarat with Muslim settlements, dating from the ninth and tenth centuries, including Khambāya (Cambay), Asāwul, Ṣaimūr, Sindān, and Sūbāra. Cambay remained a prominent port throughout history. Asāwul was later incorporated with the fifteenth century Ahmadabad and the site of Ṣaimūr has not yet been identified. Sindān, may be the same as a remote village of the same name on the coast of the Gulf of Kutch (Kachh), but the site has not yet been explored. Subāra on the other hand is likely to be the same as Bhadreśvar, also recorded as Bhīswāra, a port raided by Maḥmūd of Ghazna on his return from Somnath. Bhadreśvar retains the oldest dated Muslim monuments in India. The main mosque is a colonnaded structure with a small central courtyard and a large colonnaded portico in front of the entrance to the courtyard, a feature not seen in Banbhore and Brahmanābād. The dated structure, however, is the Shrine of Ibrāhīm, locally attributed to one Laʽl Shahbāz, bearing a Kufic inscription of 554/1160.

Numerous sites of Muslim maritime merchants are to be found in South India, in places such as Calicut, Cranganur and Cochin on the coasts of Malabar (present Kerala) and at the site of the historic Muslim port of Qā’il now called Kayalpatnam (the city of Kayal) in Tamil Nadu (still a Muslim town). The historic buildings of Malabar, dating from the fifteenth to eighteenth century, have stone walls with wooden columns and wooden tiered roofs. They do not have an enclosed courtyard and their porch usually opens to an ante-chamber leading to the prayer hall, an innovation from the planning principles seen in the earlier maritime edifices. The surviving edifices in Tamil Nadu (the historic Maʽbar of the Muslim records) are on the other hand built entirely of stone, and in their planning, with a portico opening to the prayer hall or shrine are closer in concept to the earlier maritime traditions seen in Gujarat. Numerous tombs and gravestones, from 806/1404 to recent eras include genealogies of Middle Eastern settlers. The Muslim archaeology of South India is still relatively untouched, leaving many sites throughout Tamil Nadu and Kerala to be explored and provide a better understanding of the history and cultural traditions of the maritime settlers in India and beyond.

Delhi: Muslim dominance, 1191 to mid-fourteenth century

North India was taken in 1191 by the Ghurids of Khurāsān, who, within two years established a powerful sultanate with Delhi as their capital. Their armies penetrated as far as Bengal, but the sultanate of Bengal generally remained aloof from Delhi. The Hindu Delhi was transformed to a Muslim city and in the next 150 years several other cities were built in its neighbourhood: first Kīlūgharī, founded in 685-8/1286-9; then Sīrī 698/1298-9; Tughluqābād 720/1320-21; Jahānpanāh c. 726/1326 and Fīrūzābad c. 760/1358-9. Early in the twentieth century, when New Delhi was built south of Shāhjahānābād (Old Delhi), traces of all the earlier cities were gradually buried under the new capital, except the more distant Tughluqābād, although it too is now being submerged under modern development. No systematic excavations were carried out in any of these towns and their historic urban fabric has been lost.

The architecture of the first few decades of the conquest could be crystallised into a few words: the Architecture of Dominance. It differs entirely from the architecture of the conquerors’ homelands, where arcuate engineering, with arches and domes was already in an advanced stage. The early Delhi sultans chose instead to build their mosques and tombs with temple spoil. Later with the Mongol invasion of Iran and Central Asia in 1221 causing a flood of architects, craftsmen and artisans to India, the traditions of Middle Eastern architecture, as seen in the tomb of sultan Balban and buildings of ʽAlā al-dīn Khaljī, replaced trabeate structural methods. By the fourteenth century, however, the Muslim and old Indian techniques coalesced creating a distinctive Indian architectural style, first appearing in early Tughluq buildings and reaching its maturity at the time of Fīrūz Shāh Tughluq. Yet the “Architecture of Dominance” did not die out and right up to the end of the fourteenth century was implemented in new regions conquered by the Delhi sultanate. Examples are the Jāmiʽ of Daulatabad in the Deccan, the mosques in Dhār, the early capital of Mālwa, and numerous mosques in Gujarat’s Saurashtra peninsular, mostly dating from the time of Fīrūz Shah Tughluq. This type of architecture is also seen in Jaunpur, the seat of the fifteenth-century independent Sharqī sultanate. Jaunpur was, however, devastated by the Delhi sultan Sikandar Lodī (1489-1517) sparing only a few mosques; the modern town now covers the ruins of the old.

Bengal (West Bengal, India and Bangladesh)

Muslim remains in Bengal demonstrate a marked difference from those of the rest of South Asia. Bengal, with its tropical climate and its isolation from Western India, had a substantial Buddhist culture with an ancient red-brick building tradition. Later Hindu temples were built of brick faced with blocks of stone. The Muslims inherited these traditions, rare elsewhere. The British ASI’s interest was mainly concentrated on excavation of Buddhist and Hindu sites, now mostly in Bangladesh. The ASI contribution to Muslim sites was, as usual, to clear the sites and reveal standing monuments, restoring some and preserving the ruins of selected others, but much remains to be investigated. The oldest Muslim remains, are in Tribeni (or Tribani), and are partly in ruins, but have stone walls and piers surmounted by brick arches and domes, characteristic of many later edifices. The Muslim capital, however, was Lakhnautī, the site of which is now divided between Bangladesh and India, covering a vast area of Gaur and Ḥaḍrat Pandua. The earlier buildings such as the Ādīna Masjid 776/1374 and Chota Sona mosque 899-925/1493-1519 have again stone or stone-faced walls supporting brick arches and domes, but the Buddhist influence in the former is demonstrated in the three-lobed arch of the miḥrāb, where in Buddhist iconography the arch frames the head and shoulders of the Buddha.

In later brick buildings liturgical requirements are observed, but often expressed idiosyncratically, both in planning and structural form. Many consist of a fairly small prayer hall often covered with a single dome, with a corridor in front or running around three sides of the hall. There are corner columns with the roof curved down towards the columns on all faces, imitating traditional domestic bamboo dwellings, as can still be seen in the peasant huts of remote villages. In about the fifteenth century glazed tiles were introduced in Bengal, displayed in many buildings. Most of the other sites are scattered in Bangladesh: in Bagerhat, Goardi, Mugapara, Sherpur and Sonargaon. Bagerhat and its nearby site Sherpur in particular preserve a large number of Sultanate monuments, Sherpur being rich in unreported ruins still awaiting exploration, excavation and restoration. Bengal was annexed to the Mughal Empire in 983/1575-6 by Akbar; the region has numerous sixteenth and seventeenth-century remains, including in the Bangladesh capital, Dhaka, principally a Mughal town, where the ruins of the Mughal fort and palaces attract visitors.

Mid-fourteenth to late seventeenth century: Central and South India

The brutality and mismanagement of the Delhi sultan Muḥammad b. Tughluq (1325-51) ended with the fragmentation of the Delhi Empire. Facing rebellions, the sultan himself had to remove his capital for a short time to Daulatabad in the Deccan. Well before Muḥammad’s death, independent sultanates were springing up in Maʽbar (Tamil Nadu) and the Deccan. The capital of the sultanate of Maʽbar was Madura and opposite the Hindu town is the enclosure containing the tombs of the two sultans – ʽAlā al-dīn Udaujī and Shams al-dīn ʽĀdil Shāh – housed in a domed chamber, surrounded by a colonnade, as well as a mosque and a few other tombs. In Tiruparangundram, where, in a battle with the Vijayanagar forces the last Maʽbar sultan, Sikandar Shāh, fell, a mosque has been built next to his tomb under an exposed rock.

The Deccan was at first divided into two kingdoms: the Bahmanī sultanate in the north, and in the south the Hindu Kingdom of Vijayanagar, which employed Muslims in its army and traded with the coastal Muslim communities, who sold them, among other things, numerous horses. Some of their edifices incorporate Muslim features, such as vaults and domes. The Bahmanīs, on the other hand, were devout Muslims, their founder ʽAlā al-dīn Bahman Shāh claimed Sasanian origin and the arches of their early buildings in their capital Gulbarga are crowned with a Sasanian style motif. Their structures, however, follow the North Indian style. Later, in 1429, the capital was taken to the newly-built Bidar, where the town still retains its original street layout and many monuments. In Bidar Fort the palaces employed wood extensively, but little survives, as when Bidar was falling to the Mughals the buildings were set on fire intentionally to prevent the enemy using them. Nevertheless, the prevalent high quality of the tile-work in the palaces and elsewhere indicates high levels of Deccani artistic achievement.

The Deccan, heavily influenced by Iranian culture, gradually became disposed to Sufi doctrines and by the late fifteenth century the Bahmanī realm eventually disintegrated into several smaller kingdoms: the Quṭb Shāhīs in Golkonda, where the fort and a number of edifices have survived, but are not fully investigated; the Barīd Shāhīs of Bidar who replaced the Bahmanīs and have left the ruins of some palaces in the fort and numerous tombs and shrines; the ʽĀdil Shāhīs of Bijapur and a number of smaller sultanates of short duration. The most significant archaeological remains are those of the ʽĀdil Shāhīs who built Bijapur as their new capital. Unlike other Muslim cities Bijapur has a roughly circular plan, approximating Hind urban planning, but Bijapur’s architecture is markedly original, developed from that of the Bahmanīs. The ʽĀdil-Shāhī territory went as far west as Goa which was taken by the Portuguese in 1510, but in the nearby town of Ponda stands the Ṣafā Masjid, a curious hybrid of ʽĀdil Shāhī architectural traditions and those of the maritime settlers.

Fifteenth to mid-sixteenth century: West India

The small and short-lived sultanate of Mālwa (1392-1531), set between Gujarat and the Deccan, has left many fine edifices, both in its first capital, Dhār and the second, Mandu. The major historical remains in Dhār are the mosque of Sultan Dilāwar Khān 808/1405-6; the fifteenth-century Kamāl Maulā mosque and tomb; and the Lāt ki Masjid, named after a pre-Islamic iron pillar originally re-erected in front of it; the broken pieces being preserved on the site. Mandu was built over a natural flat summit of a hill, and in its fort many palaces, ornamental reservoirs, and other historic edifices are preserved, some in fairly good condition. Marble, sometimes inlaid with other stones was favoured, and the seventeenth-century marble architecture of Shāh Jahān is indebted to Mandu, as it was his headquarters as a prince.

One of the archaeologically richest and also best-studied areas of West India is Gujarat, with numerous Islamic sites from both the pre- and post-conquest period. There is a legend in the Muslim world, unfounded but current at least since from the early eleventh century, that in the very early days of Islam the pagans of Mecca smuggled the idol Manāt – whose worship was forbidden in the Qur’an (LIII, 19-25), together with the worship of Lāt and ‘Uzzā – via the maritime route to Somnath, providing an excuse for Maḥmūd of Ghazna to sack the holy temple of Somnath in 1025-6. Somnath, a Hindu pilgrimage city – and its neighbouring towns, Veraval, Mangarol and Junagadh – retain large Muslim populations who are custodians of their edifices. This is not the case with the Jāmiʽ of Somnath which is built out of temple spoil near the site of a demolished ancient temple, and now serves as a museum displaying Hindu and Jain images, inflating the already uneasy Hindu-Muslim relationships in the town – exploited by local and national politicians. The Jāmiʽ is apparently later in date than other mosques, the Chaugān and Idrīs Masjids, both under Muslim custodianship and, in spite of their fourteenth-century origin, well preserved.

Gujarat was annexed to the sultanate of Delhi only in 1297 – a century later than the conquest of Delhi. Jalor and Sanchor, now in Rajasthan, were historically the borderland between Delhi and Gujarat territory, and the Jāmiʽ of Jalor seems to have been constructed in the early days of the conquest and completed at the time of Ghiyāth al-dīn Tughluq in 1325. Some aspects of pre-conquest Muslim traditions continue to be seen in Gujarat and the only influence from Delhi may be in the use of temple spoil and the introduction of a screen wall in front of the prayer hall, first seen in the Jāmiʽ of Cambay, and later to become a prominent and highly decorative feature in the architecture of the Gujarat sultanate. The rich architecture of this period, including mosques, shrines, step-wells, lake-size reservoirs and even temples built with the sultans’ permission were studied by James Burgess.

North-west India, fifteenth century to the Mughal era

To the north of Gujarat the state of Rajasthan was nominally under the dominance of Delhi, but apart from certain areas: Ajmer and the regions of Nagaur and Bayana, the rest remained in the hands of the Hindu Rajputs, whose descendants made affiliations with the Mughals, some remaining influential in places such as Jodhpur, Jaipur and Jaisalmer. Rajasthan’s arid terrain, Tīmūr’s attack on Delhi and the consequent debilitated central power in Delhi during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries contributed to the rise of autonomous – if not independent – principalities in Nagaur and Bayana. Shams Khān, the first independent ruler of Nagaur, was the brother of Muẓaffar Shāh, the first Gujarat sultan, and the subsequent Khāns of Nagaur kept a close but guarded relationship with their relatives. Nagaur’s architecture of this period is an amalgamation of Delhi and Gujarat styles. Nagaur has an irregular circular fort founded in the early twelfth century, and among the remains of the Delhi sultanate is the impressive fourteenth-century Buland Darwāza. The independent Khāns, however, transformed the city to a smaller – but humbler and more modest – replica of their cousins’ capital, Ahmadabad, complete with a royal square with a ceremonial gate at one end imitating the Tin Darwāza of Ahmadabad. Numerous mosques of the Khāns are scattered around the town.

To the west of the region of Nagaur, Bayana’s strategic position on the route from Delhi to Gwalior and the Deccan, combined with a formidable fort and natural and agricultural resources ranging from red sandstone to sugar and indigo, made it, in spite of its harsh desert environment, a prized possession of its Hindu and, later, Muslim rulers.The two substantial monuments of the early Muslim period are the Jāmiʿ (now known as Ukhā Mandīr mosque) and its open prayer-ground (ʿīdgāh). Other early fourteenth-century remains include the reservoir known as Jhalār Bāʾolī, and an extension to the Jāmiʿ (known as Ukhā Masjid). These laid down a regional style displayed in the later monuments of the autonomous Auḥadī Khāns of the fifteenth century and also those of Sikandar Lodi. The architecture of Bayana, isolated from Delhi, flourished independently with its own diverse characteritics. The most significant architectural contribution of the Auḥadīs is the urban development in the Fort (destroyed in an earthquake in 1505 and abandoned afterwards) preserving the original street layouts, still unexplored, together with mosques, a lofty minaret dated 861/1456-7, the rulers’ mansion and numerous houses, leaving us with examples of fifteenth and sixteenth-century domestic dwellings.

With the decline of Bayana in the sixteenth century we enter the Mughal era, with its outstanding monuments featuring elements first seen in Bayana. While the major Mughal monuments were the first to be restored and are well-documented many sites of the Muslim era await perusal, for excavation and examination of the still functioning historic urban fabric of numerous provincial towns, so far ignored by archaeologists, architects and urban designers alike. In short Muslim archaeological sites in the subcontinent are under-studied and hardly excavated systematically. Much is left for present and future archaeologists to explore.

Maʿbar (Mabar) history, art and architecture, EI3, 2021, pp. 117–125, figs 1–3.

Maʿbar (Mabar, Tamil Nadu, India), called “the key to India” by Rashid

Al-Dīn, was the Muslim name for the Coromandel Coast, chronicled from

the early thirteenth century. Abuʾl-Fidāʾ places it east of Cape the early thirteenth century. Abuʾl-Fidāʾ places it east of Cape

Comorin, noting its towns: Manīfatan and Biyardāwal, where horses

were landed. Chinese exports to the ports of Maʿbar were exchanged

with goods from the Persian Gulf and as far as Europe; Marco Polo

mentions the main import as Persian Gulf horses with an annual quota

of 11,400 head. Early in the fourteenth century the area was under the

Delhi sultanate, followed by a brief sultanate established by Aḥsan Shāh

in c. 734/1333-4 which terminated in 779/1377-8, when Sikandar Shāh

was slain by the Vijayanagar forces. His tomb and those of other sultans

are kept as shrines, Sikandar Shāh’s displaying the long-established architectural

and artistic traditions of the region.

Madura, the tomb of Sultan ʿAlā al-Dīn Udaujī (c. 1334–1339) and

Shams al-Dīn ʿĀdil Shāh (c. 1356–1373), view from the

east. The dome is carved out of a single piece of rock. The tomb

of Sayyid Ḥusain Quddus’ullāh, said to have been ʿAlā al-Dīn’s

vizier, is in the foreground and the minaret of the mosque of the

site can be seen on the right.

Kayalpatnam, Jamiʿ al-Ṣaqīr mosque or the Kayalpatnam, Jamiʿ al-Ṣaqīr mosque or the

Khuṭba Śirupaḷḷi (c. 13th–early 14th century),

interior looking west. The antiquated form of

the monolithic columns and their capital brackets

supporting the lintels of the roof structure can

be seen.

Kayalpatnam, the tomb of Shaykh

Sulaymān (d. 1079/1668–9), a stone

building with its roof imitating a timber

structure, and featuring three finials

adopted from Hindu and Buddhist

architecture, but also common in

South Indian Muslim buildings.

The Muslim architecture of Maʿbar is manifested in its major cities, particularly Kayalpatnam and Madura. The tomb of ʿAlā al-Dīn Udaujī is said to have been constructed by Shams al-Dīn ʿĀdil Shāh, who was buried beside him, but other mosques and tombs are not directly related to the sultanate and some in Kayalpatnam are probably earlier. Unlike in North India, the mosques of Maʿbar are free-standing covered halls without a defined courtyard, and many have a colonnaded portico in front. Their stone construction with ornamentation based on the Hindu repertoire, displays a synthesis of artistic styles. Nevertheless, Ibn Baṭṭūṭa also speaks of grand wooden structures near Madura and in Kayalpatnam three stone tomb-chambers remain, with roofs which imitate the form of wooden hipped roofs.

The mosque and tomb of Sikandar Shāh

(r. c.774–9/1373–7), Tirupurangundram.

Above: view from the rocks of the battlefield

where the sultan perished. Below: the front

colonnade, the monolithic columns incorporate

motifs common to South Indian Hindu and Muslim

architectural decoration.

The artistic achievement and traditional planning of the Muslim architecture of Maʿbar is displayed in the mosque attached to the tomb of Sikandar Shāh, set on the summit of a hill near the town of Tirupurangundram. The shrine is believed to be on the site of his death and burial in a grave with a simple tombstone beneath a great rock jutting diagonally out from the ground. The present edifice consists of two parts, a mosque at the eastern side and a square tomb chamber incorporating the rock at the west. The finely-ornamented mosque consists of a front porch opening to an ante-chamber which leads to the prayer hall. The highly decorated columns of the porch support the lintels, the soffits of which are embellished with foliage patterns. These decorative features are shared with the Hindu ornamentation of the early Vijayanagar period, but of course exclude figurative elements. Similar columns are found in other Muslim buildings of Madura but none as refined or elaborate as those in this building.

Bayana: the Sources of Mughal Architecture, Edinburgh University Press,

Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies, pp. 768 with 352 colour photographs

and 255 monochrome photographs, maps and diagrams; appendices;

bibliography; index.

ISBN 978 1 4744 6072 9 (Hardback), ISBN 978 1 4744 6075 0 (Webready PDF),

ISBN 978 1 4744 6074 3 (EPUB). In print, publication date 31 March 2020.

Bayana, were it not for its shortage of water, might have been the capital of India. Agra and Fathpur Sikri, the capitals of the mighty Mughals were once mere villages of Bayana. Situated in south-eastern Rajasthan, Bayana held a strategic position on the ancient route from Delhi to Gwalior and the Deccan, combined with an impregnable fort and natural and agricultural resources. The Moroccan traveller, Ibn Battuta, who had seen fine mosques and great cities from Cordoba to Cairo, Delhi and Khanbaliq (Beijing) visited Bayana in 1342 and found it so impressive that he called it a “great city” and its congregational mosque “one of the finest”. The mosque still stands, along with many other monuments.

The Fort, called Tahangar, also preserves the layout of its own walled town with gates, markets, palatial dwellings, and even ordinary houses dating from the fifteenth century. To deal with the aridity of this desert region, water was harnessed for utility in reservoirs and stepwells, embellished to also provide private and public places of resort.

Between Timur’s (Tamerlane’s) invasion of Delhi in 1398 terminating the empire of the Delhi sultanate, and the rise of the Mughal empire in the mid-sixteenth century, India had fragmented into small independent sultanate states or autonomous principalities.

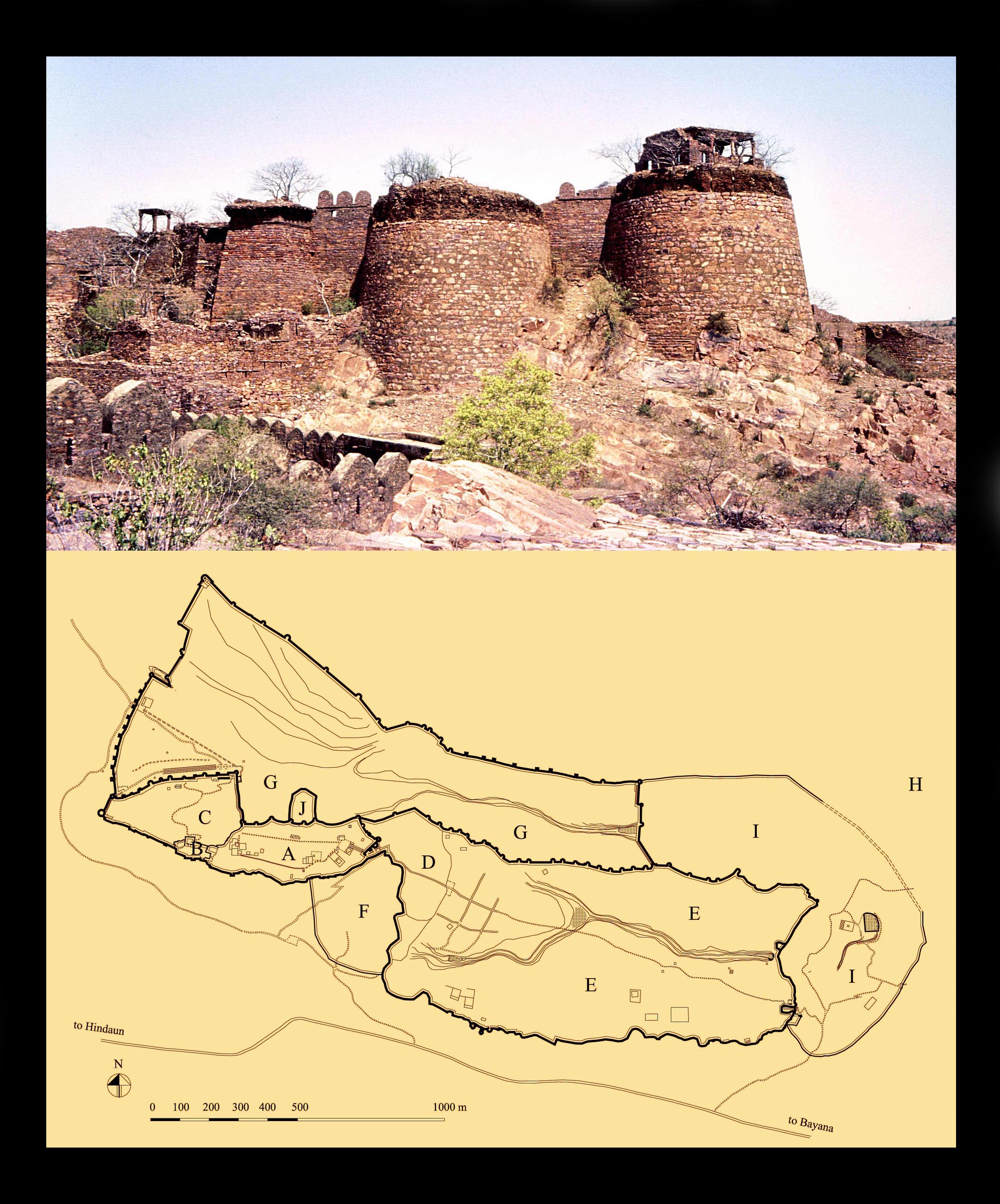

A corner of the impregnable fortifications of the

citadel (A in map), within the much larger Tahangar

Fort. The origin of the site is pre-Islamic, but it was

almost entirely rebuilt by the Muslims with massive

ramparts and circular towers.

In architecture, the Delhi style, which had dominated most of the northern regions was transformed during this period, and in many areas regional styles developed, some of which – such as those of the Deccan, Malwa and Gujarat – have been studied in some detail in the past, but not Bayana.

The `Idgah of Bayana, the prayer ground

for Muslim festive days, built by Baha al-din

Tughrul in the last days of the twelfth century.

It is the oldest standing structure of its kind

in India and probably the world.

Bayana, controlled in the fifteenth century by the Auhadi family, was a key player among these states, with its formidable fort as the Auhadi’s power base. They bore the title of Khan and while not claiming to be sultans, ruled independently from Delhi and occasionally took sides with the Sharqi sultans of Jaunpur.

The Chaurasi Khamba Mosque, built at the end of the

twelfth or the first years of the thirteenth century out

of temple spoil in the northern borderland between

the territory of Bayana and Delhi. The inscription of

the mosque declares Baha al-din Tughrul as sultan.

The mosque itself has preserved most of its original

features, including its mihrab (the prayer niche marking

the direction of Mecca), the royal gallery at the right

(north) side of the prayer hall and the stone minbar or

pulpit, the oldest surviving specimen of its kind in India.

The Ukha Masjid, an extension to Baha al-din’s congregational mosque, added in 1320-21

during the reign of the Delhi Sultan Mubarak Shah Khalji. Left: the entrance seen from the

courtyard. Right: the elegant central mihrab in the prayer hall. Constructed entirely of local

red sandstone, which later was to become the hallmark of the Mughal Emperor Akbar’s

buildings, the mosque has many details which were later adopted by Mughal architects. The

subtle, well-balanced and impressive design of the mosque left a life-long impression on Ibn

Battuta who visited it only twenty-one years after its construction and remarked: “It is one