Fatehabad, inscribed column, erected by Firuz Shah Tughluq in the town he built on the site where his investiture was established after challenges from Delhi failed. The inscription sets in stone the events of the Tughluq dynasty from the death of the founder, sultan Ghiyath al-din, to the beginning of Firuz Shah’s reign.

This previously unstudied inscription is documented line by line in 70 plates, each plate containing four or five photographs. The book also records other inscriptions from Fatehabad, as well as towns of the region including Barwala, Hansi and Hisar. The earliest inscription is at Hansi, dating from the time of Muhammad b. Sam who conquered north India at the end of the twelfth century, up to one from the time of the Mughal Emperor Humayun dating from Ramadan AH 944 (February-March 1538 AD). Although Mughal inscriptions were not intended to be included in this volume, this very early Mughal example is significant as it records the construction of a tomb for an ordinary soldier who remained loyal to his troubled monarch and lost his life in battle. His body, along with those of some other soldiers, was buried outside the town walls of Hisar and by the order of the emperor magnificent domed buildings ‒ suitable for high ranking courtiers ‒ were built at considerable cost over their graves.

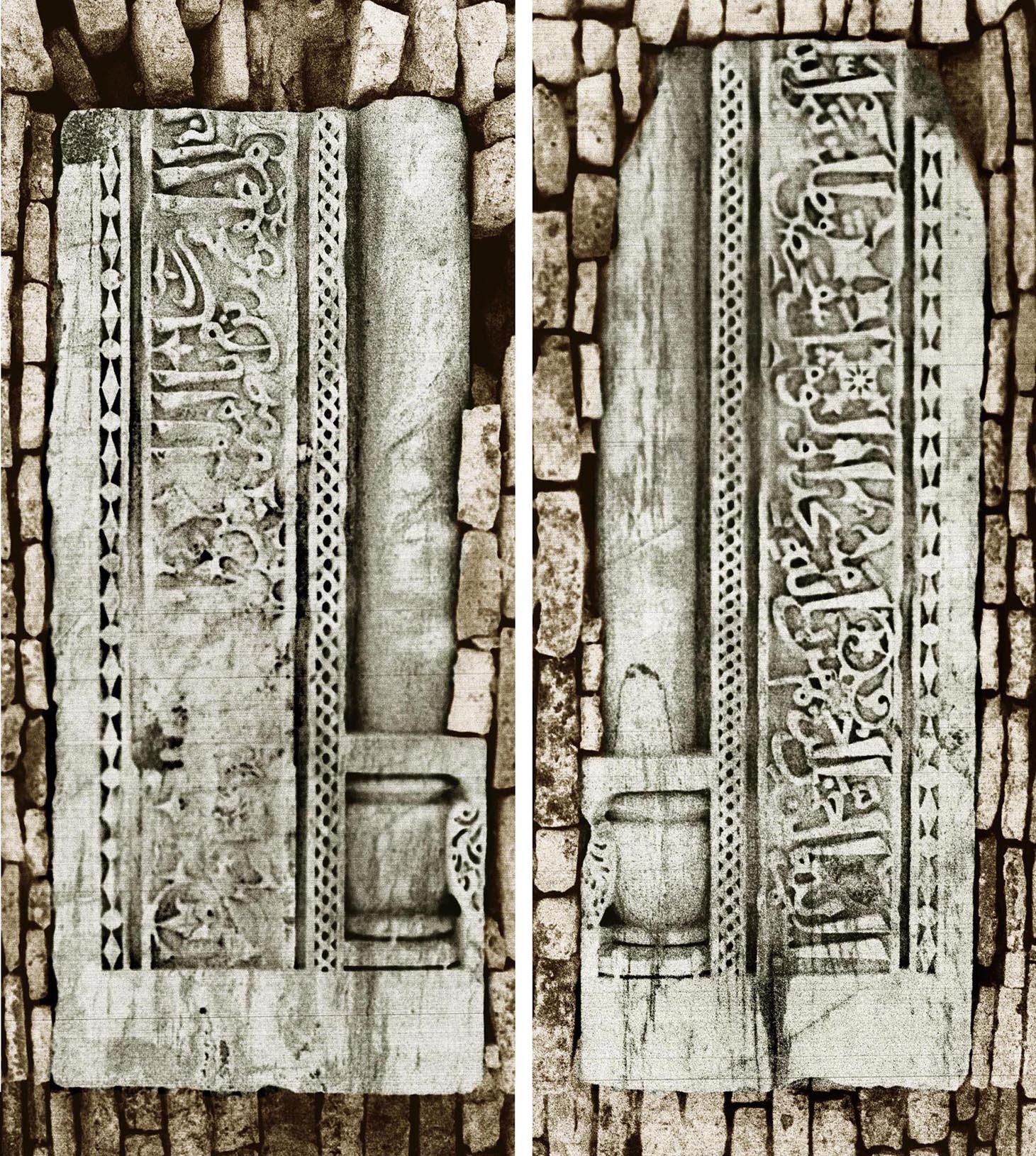

Hansi, two fragments of an inscription of Muhammad b. Sam,

which ran originally around a doorway or a prayer niche (mihrab)

of a mosque. These fragments, together with others from the same

sultan found in various parts of Rajasthan and Haryana, confirm the

historical records that from the very beginning

Muslims had firm control of northern India.

Haryana I can be ordered directly from SOAS, http://store.soas.ac.uk, e-mail: onlinestoreenquiries@soas.ac.uk

Bhadresvar, the Oldest Islamic Monuments in India, M Shokoohy with contributions by Manijeh Bayani-Walpert and N. H. Shokoohy (Studies in Islamic Art and Architecture, Supplements to Muqarnas, vol. II) (E. J. Brill) Leiden – New York ‒ Copenhagen ‒ Cologne, 1988, 84 pp., 42 line drawings, 119 monochrome photographs, appendix, index.

Bhadresvar, the Oldest Islamic Monuments in India, M Shokoohy with contributions by Manijeh Bayani-Walpert and N. H. Shokoohy (Studies in Islamic Art and Architecture, Supplements to Muqarnas, vol. II) (E. J. Brill) Leiden – New York ‒ Copenhagen ‒ Cologne, 1988, 84 pp., 42 line drawings, 119 monochrome photographs, appendix, index.

ISBN: 90 04 08341 3

ISSN: 0921-0326

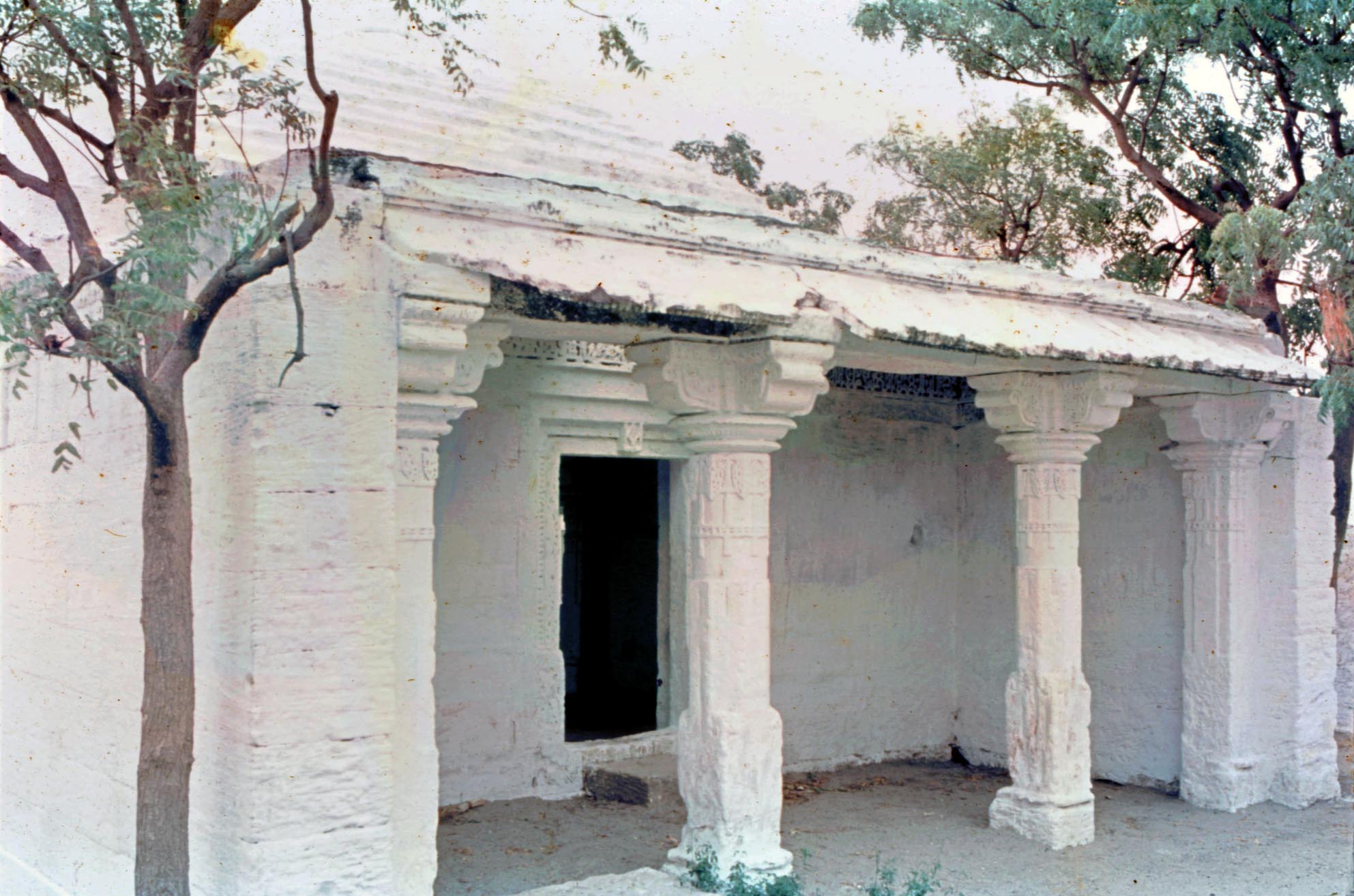

Bhadresvar, Shrine of Ibrahim, the earliest standing Islamic monument in India.

Islam was first introduced to India, not by conquering armies, but by merchants plying the Indian Ocean from Arabia and Persia to South India and beyond, from at least the ninth century, if not earlier. While the presence of such trading communities was recorded by tenth and eleventh century Muslim geographers no physical evidence of an early settlement had come to light until the discovery of the monuments of Bhadresvar (Bhadreshwar) on the Gujarat coast of Kutch (Kachh), which are presented in this book with survey drawings of the monuments supported by photographs.

Islam was first introduced to India, not by conquering armies, but by merchants plying the Indian Ocean from Arabia and Persia to South India and beyond, from at least the ninth century, if not earlier. While the presence of such trading communities was recorded by tenth and eleventh century Muslim geographers no physical evidence of an early settlement had come to light until the discovery of the monuments of Bhadresvar (Bhadreshwar) on the Gujarat coast of Kutch (Kachh), which are presented in this book with survey drawings of the monuments supported by photographs.

One of the edifices, the shrine of Ibrahim also locally known as the shrine of La`l Shabaz, bears an inscription dated AH Dhi’l-hijja 554 (December 1159-January 1160 AD), the earliest Muslim date on a building in situ in India, some forty years before the Muslim conquest of Delhi and nearly a century and a half before the Muslim conquest of Gujarat. Near the shrine two mosques, the Solahkhambi and the Chhoti Masjid, along with many epitaphs, are also datable to the same period. A chapter considers a mosque at Junagadh in Gujarat. This mosque, built for the use of Muslim settlers by their chief merchant, the shipmaster Abu’l-Qasim, while later than the shrine of Ibrahim, is still prior to the Muslim conquest of the region.

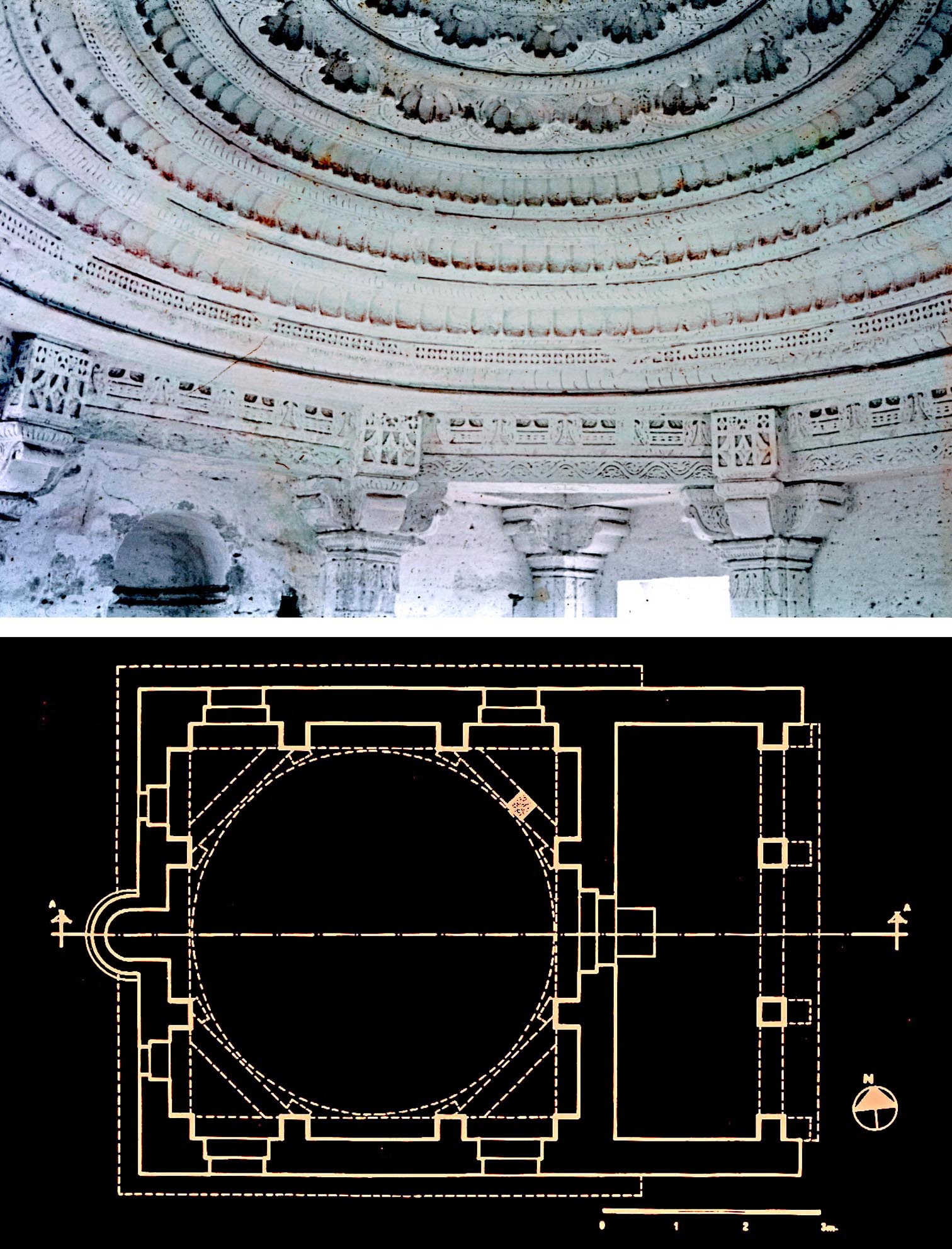

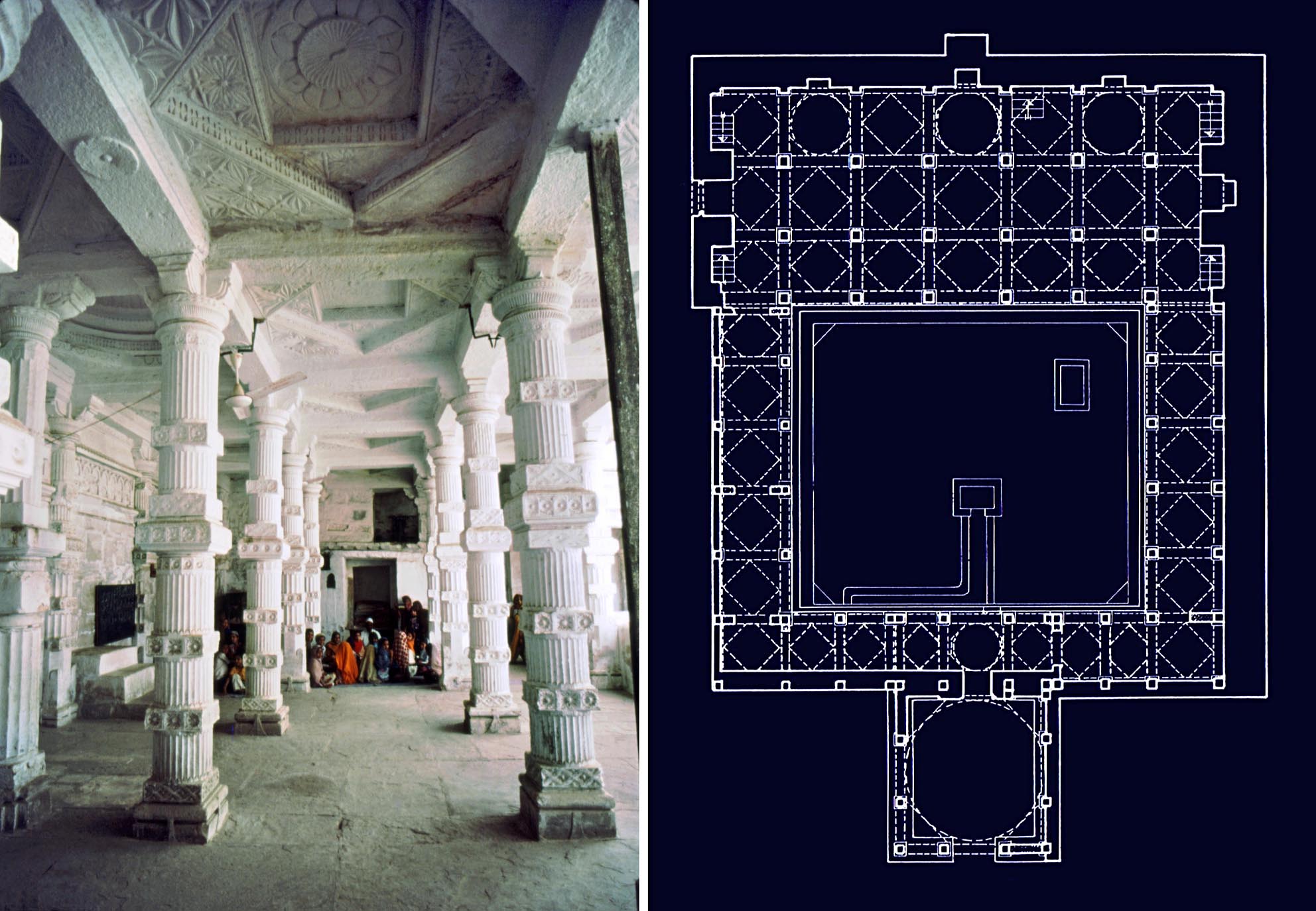

Shrine of Ibrahim, built by a community of maritime

merchants almost half a century before the Muslim

take-over of Delhi: plan and a view of the interior

displaying its traditional Indian decoration.

The maritime merchants' buildings were constructed by local non-Muslim craftsmen who employed the techniques and decorative patterns of Hindu and Jain architecture, but the buildings are Muslim in concept; orientated towards Mecca and with a prayer niche (mihrab) to mark the direction. They have, however, elements such as front porticoes, not seen in the Muslim architecture of North India, but which became a distinctive feature on the maritime littoral of western and southern India.

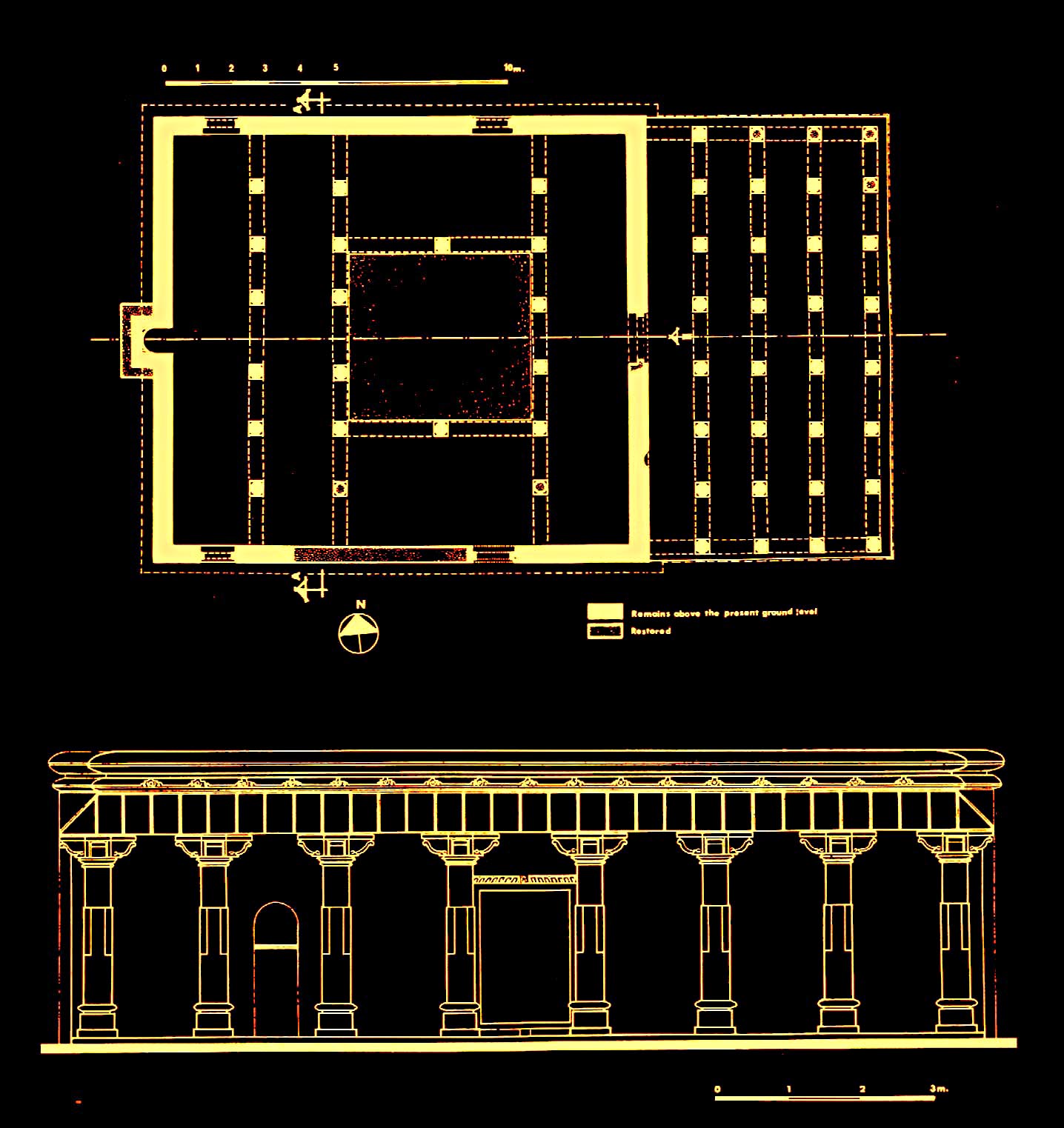

Solahkhambi mosque, plan and elevation, showing the building in its original condition. The large portico in front of the entrance to the courtyard has a subsidiary prayer niche, indicating that in addition to the prayer hall the portico was also used as a space for worship.

Available from major booksellers or directly from E. J. Brill at www.brill.com

Nagaur, Sultanate and Early Mughal History and Architecture of the District of Nagaur, India, M. and N. H. Shokoohy (Royal Asiatic Society Monograph XXVIII) London, 1993, 184 pp., 72 line drawings, 132 monochrome photographs, appendices, index.

Nagaur, Sultanate and Early Mughal History and Architecture of the District of Nagaur, India, M. and N. H. Shokoohy (Royal Asiatic Society Monograph XXVIII) London, 1993, 184 pp., 72 line drawings, 132 monochrome photographs, appendices, index.

ISBN: 978 0947593094

When Masʽud, the Ghazni sultan Mahmud’s son died the mighty Ghaznavid empire disintegrated. The later Ghaznavids ‒ no match for the Ghurids and the emerging Seljuqs ‒ could not even retain their ancestral capital Ghazna. Their lives were often cut short, one sultan replacing the other, except Sultan Bahram Shah (1118-1152 AD) who, while unable to extend his kingdom northwards, learned from his ancestors, and looked towards India for new territory. The fort of Nagaur, one of the oldest Muslim strongholds in India, is claimed to date from this period and was founded by his, not so loyal, governor, Bahalim, whose name suggests that he was a convert or perhaps still a Hindu. This may account for the original town plan of Nagaur, which may have been concentric in the ancient Indian tradition, rather than the Perso-Islamic design adopted by the Ghaznavids for all their cities.

Although nothing of the Ghaznavid era survives except perhaps the layout of the perimeter of the fort, the town and its surrounding district preserve numerous sultanate and early Mughul monuments displaying a strong architectural style which developed in the locality. Nagaur was also a centre for the Chishti sufis of India, whose buildings in the region are among the finest monuments of northern India, and are exemplified by a great gateway: the Buland Darvaza of the Khanaqah al-Tarikin (see front cover in List of Publications). The form of this gate has inspired the design of many others in the region right up to the time of the Emperor Akbar.

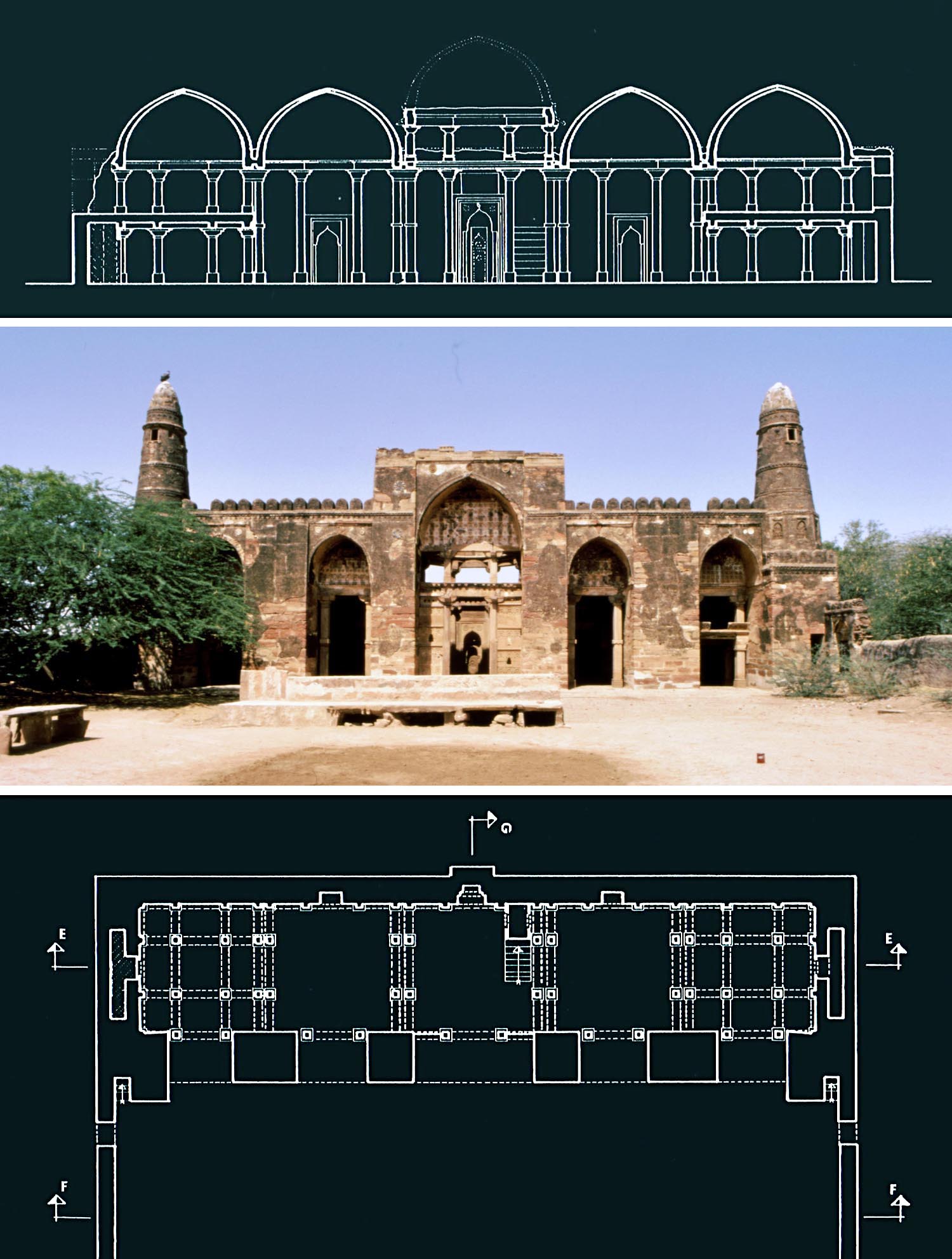

Nagaur, Shams Khan Masjid, the old congregational mosque of Nagaur built together with a lake-sized reservoir between AD 1412 and 1419 by the founder of the autonomous dynasty which for over a century controlled a large principality bordering the territories of many hostile Rajputs.

During the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries Nagaur became the capital of an autonomous dynasty founded by Shams Khan, a brother of Muzzafar Shah, the founder of the Gujarat Sultanate. The book gives a detailed account of the Islamic buildings of the region from the twelfth century to the Mughal period, with descriptions of the monuments supported by original surveys and photographs.

During the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries Nagaur became the capital of an autonomous dynasty founded by Shams Khan, a brother of Muzzafar Shah, the founder of the Gujarat Sultanate. The book gives a detailed account of the Islamic buildings of the region from the twelfth century to the Mughal period, with descriptions of the monuments supported by original surveys and photographs.

Didwana, Qil`a Masjid (the Fort mosque), the congregational

mosque of the town, built between AD 1435 and 1452 by Shams

Khan’s son Mujahid Khan.

Many edifices also bear inscriptions, which throw light in particular on the history of the independent khans who controlled the region of Nagaur until the establishment of the Mughal Empire. Through the inscriptions ‒ the texts and photographs of which are given in Rajasthan I ‒ and other historical sources, including the sufi records, the previously little-known history of the region from the Ghaznavid period until the establishment of Mughal control is investigated. The work considers the whole region and records the edifices of other towns including Chinar, Didwana, Khatu, Ladnun, Mandor and Naraina. Nagaur has become the most comprehensive source for the Islamic architecture of the region, and was also a catalyst for the rehabilitation of the Rajput structures within Nagaur fort.

Many edifices also bear inscriptions, which throw light in particular on the history of the independent khans who controlled the region of Nagaur until the establishment of the Mughal Empire. Through the inscriptions ‒ the texts and photographs of which are given in Rajasthan I ‒ and other historical sources, including the sufi records, the previously little-known history of the region from the Ghaznavid period until the establishment of Mughal control is investigated. The work considers the whole region and records the edifices of other towns including Chinar, Didwana, Khatu, Ladnun, Mandor and Naraina. Nagaur has become the most comprehensive source for the Islamic architecture of the region, and was also a catalyst for the rehabilitation of the Rajput structures within Nagaur fort.

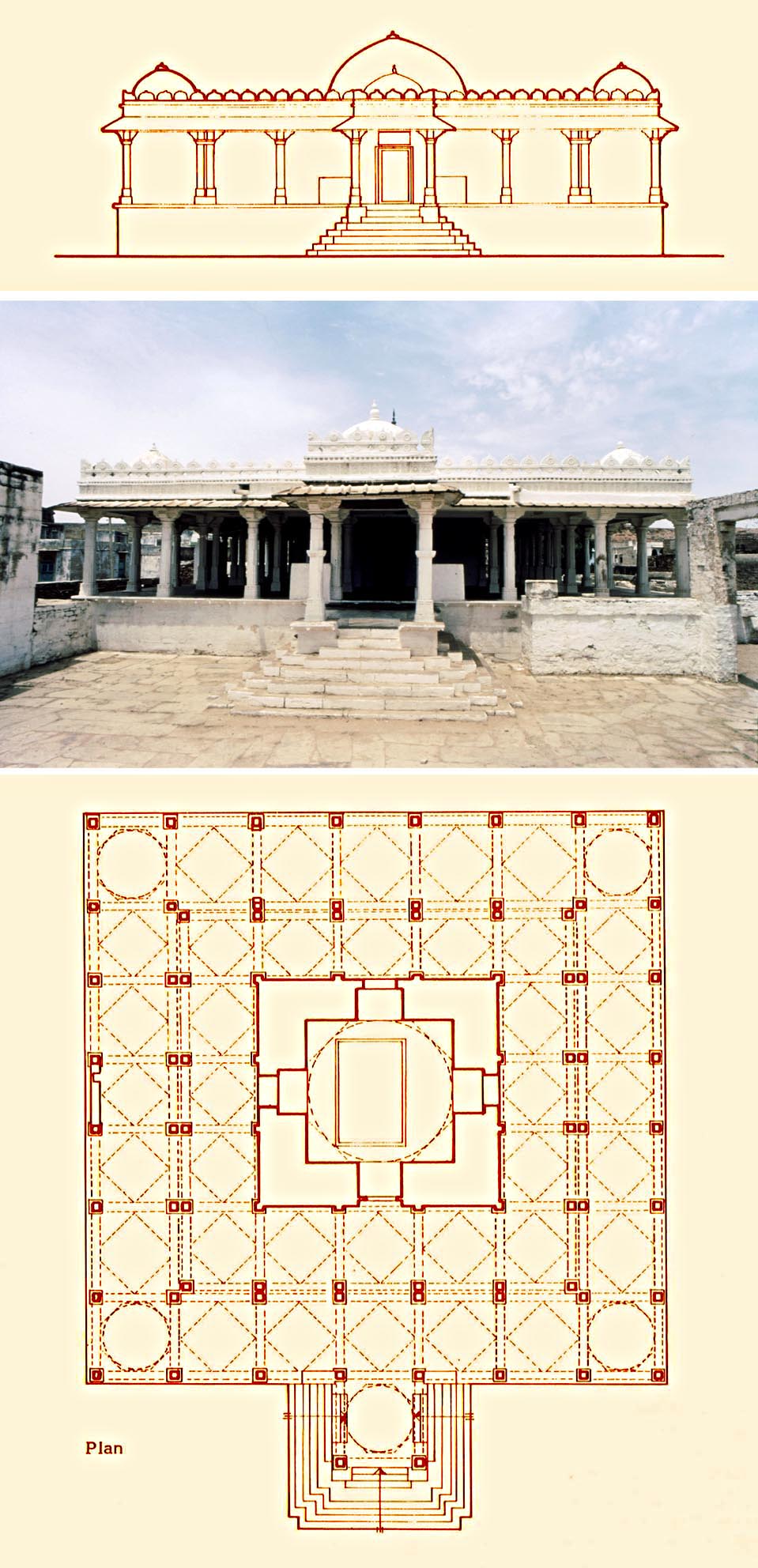

Bari Khatu, Shrine of Baba Ishaq Maqribi, a celebrated Sufi of the Maqhribiya sect, who resided in Khatu in the late fourteenth century. His follower Shaikh Ahmad, who moved from Khatu to Gujarat, became the spiritual leader of the sultans of the region. The building which houses the tomb of Baba Ishaq dates from the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century.

Originally published by the Royal Asiatic Society, distributed by Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group www.routledge.com

Kirtipur, An Urban Community in Nepal - its People, Town Planning, Architecture and Arts, edited and with contributions by M. and N. H. Shokoohy, (Araxus) London, 1994, 258 pp., 150 plates, 17 maps, 38 architectural drawings, 18 inscriptions, 10 graphs and tables.

Kirtipur, An Urban Community in Nepal - its People, Town Planning, Architecture and Arts, edited and with contributions by M. and N. H. Shokoohy, (Araxus) London, 1994, 258 pp., 150 plates, 17 maps, 38 architectural drawings, 18 inscriptions, 10 graphs and tables.

ISBN: 978-1-870606-02-8

Kirtipur’s central public square in 1986 with De Pukhu a reservoir with both religious and secular functions. It is surrounded by traditional houses, although many have now been modernised.

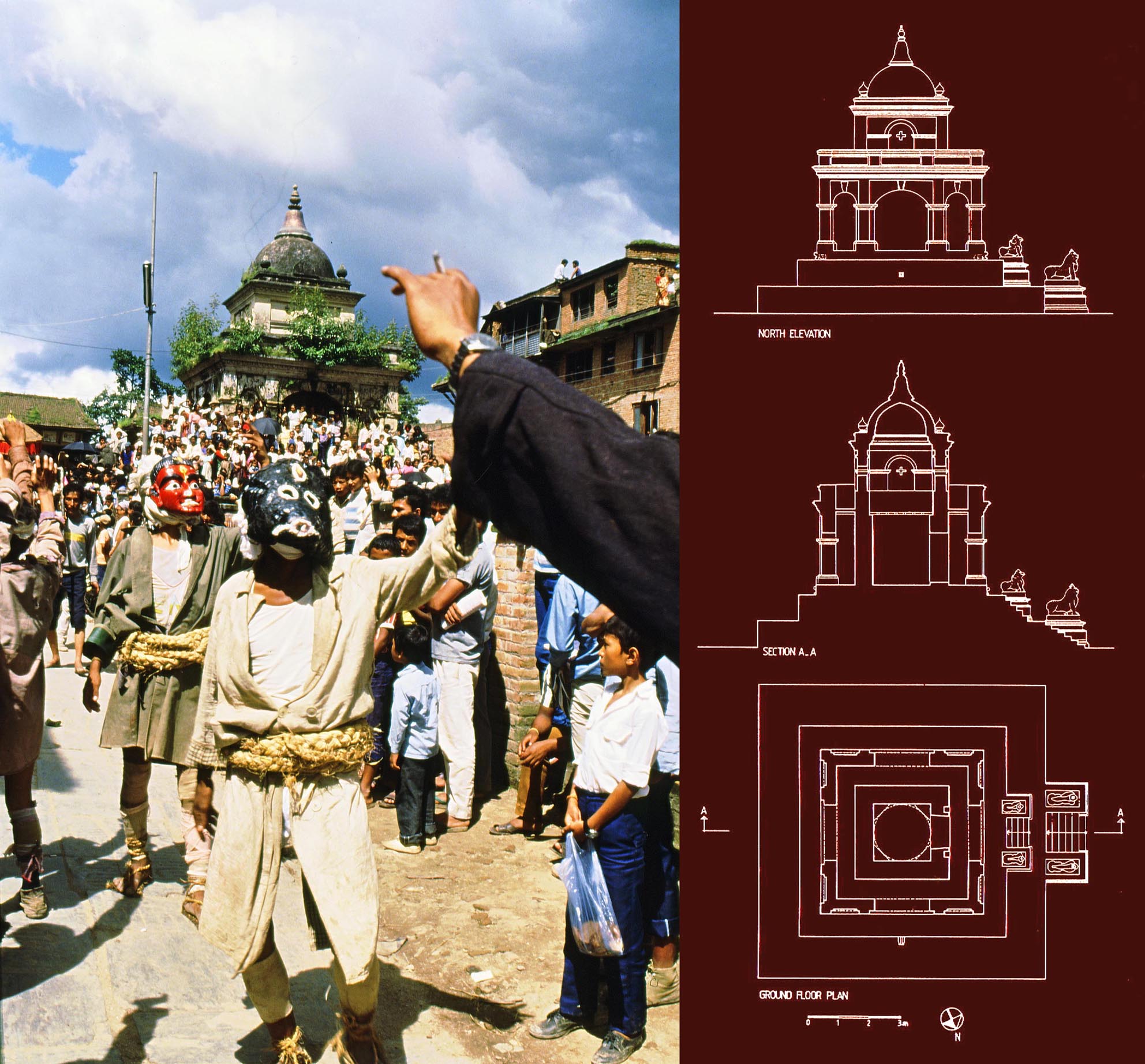

Kirtipur is the fourth largest town in the Kathmandu Valley but for historical reasons had remained cut off from modern infrastructure and development. The study of the town was carried out as a joint effort between the School of Architecture and Landscape at the University of Greenwich and the townspeople of Kirtipur with the co-operation of the Government of Nepal. The aim was to investigate the historic and cultural heritage and present condition of the town, to provide evidence of its religious and secular architecture and the evolution of its planning, and give background information which could be used in the future for proposals for development. The project began in 1986, and along with a number of articles the book brought the unique qualities of this town to wider attention. Several projects were initiated and carried out by townspeople to restore historic structures in the traditional style. A chapter of the book was part of the course work for students from Cornell University, which established a centre in Kirtipur. The project has continued with the publication of a book on the towns inscriptions (in Nepali, by Sukra Sagar Shrestha), and Street Shrines of Kirtipur in 2014.

Kirtipur has a complex social structure, unified by ethnic and cultural bonds, but diverse in the hierarchy of its social groups. It preserves elements of its rural society in close proximity to Kathmandu and Patan, which are becoming increasingly metropolitan. Kirtipur is inhabited by Newars, the most ancient population group in the valley, known for their artistic skills, and responsible for the much admired architectural forms which have produced the townscapes of the Valley. The town has preserved many elegant old houses and a number of important religious Buddhist and Hindu buildings. In Newar society the sacred and secular are closely connected, and all elements of the built environment have a sacred dimension, which still governs their use in spite of evolving social conditions. Simple dwellings and the arrangement of the quarters of the town are discussed along with the prominent religious monuments. Until recently the lack of roads to the town, as well as limited vehicular access within it because of the stepped lanes, had inadvertently controlled development and had an important role in preserving the urban fabric intact.

Kirtipur has a complex social structure, unified by ethnic and cultural bonds, but diverse in the hierarchy of its social groups. It preserves elements of its rural society in close proximity to Kathmandu and Patan, which are becoming increasingly metropolitan. Kirtipur is inhabited by Newars, the most ancient population group in the valley, known for their artistic skills, and responsible for the much admired architectural forms which have produced the townscapes of the Valley. The town has preserved many elegant old houses and a number of important religious Buddhist and Hindu buildings. In Newar society the sacred and secular are closely connected, and all elements of the built environment have a sacred dimension, which still governs their use in spite of evolving social conditions. Simple dwellings and the arrangement of the quarters of the town are discussed along with the prominent religious monuments. Until recently the lack of roads to the town, as well as limited vehicular access within it because of the stepped lanes, had inadvertently controlled development and had an important role in preserving the urban fabric intact.

Chilancho Stupa, one of the oldest stupas of Nepal with subsidiary

stupas at the corners of its vast platform. Local tradition holds that

it was founded by the Emperor Asoka. Its present form dates from

the sixteenth century with an earlier core, and its original exposed

brickwork is the best-preserved example of its kind.

The whole town turns out for important Newar religious festivals. Here the stepped platform of the Narayan Temple (plan, section and elevation before reconstruction of its roof, to the right) is transformed into an open-air amphitheatre.

A number of specialists from Nepal, some from Kirtipur, as well as other scholars contributed to the book. Marc Barani writes on “The residential unit - symbolic organization”; Padam B. Chhetri on “Kathmandu Valley Land Use Plan and Kirtipur”; Robin Lall Chitrakar on “Water supply and sanitation”; Chris Miers on “The Newari house”; Shanker M. Pradhan on “Land use and population survey”; Gauri Nath Rimal on “Private and public involvement in conservation policy development”; Ramendra Raj Sharma on “Traditional houses of Kirtipur, their types and their building materials”. Sukra Sagar Shrestha, Chief Archaeologist of the Nepal Department of Archaeology and a resident of Kirtipur writes on “Social life and festivals”, “Historic public buildings” and “Arts and antiquities” as well as providing material presented in the appendices. Uttam Sagar Shrestha, also a resident of Kirtipur, contributes on “Land use changes in Kirtipur” and “Road transport and communications”; and Professor Sudarshan Raj Tiwari of Tribhuvan University on “Tiered temples of Kirtipur, a study of their form and proportion”. Mehrdad Shokkohy’s contribution includes an introduction and chapters on “History”, “The Newars, the people of Kirtipur”, “Urban fabric” and “Tourism and its effects on Kirtipur”. Natalie Shokoohy was instrumental in editing the contributions and also contributed the chapter on “Buddhist Monasteries”.

The appendices consist of “Inscriptions of Kirtipur”; “Images from Chilancho Vihar preserved in the National Museum Kathmandu”, and “Images from Mul Bhagvansthan, Chilancho Mahavihar” also preserved in National Museum Kathmandu.

Available from major booksellers or directly from www. araxus.org, e-mail: sales@araxus.org

Muslim Architecture of South India, the sultanate of Ma‘bar and the traditions of the maritime settlers on the Malabar and Coromandel coasts (Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Goa), M. Shokoohy, (Routledge Curzon Studies in South Asia) London and New York, 2003, 304 pp., 116 figures including survey drawings, maps and old engravings, 234 monochrome plates, appendices, lists, bibliography, index.

Muslim Architecture of South India, the sultanate of Ma‘bar and the traditions of the maritime settlers on the Malabar and Coromandel coasts (Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Goa), M. Shokoohy, (Routledge Curzon Studies in South Asia) London and New York, 2003, 304 pp., 116 figures including survey drawings, maps and old engravings, 234 monochrome plates, appendices, lists, bibliography, index.

ISBN: 978-0-415-30207-4 (hb)

ISBN: 978-0-415-86645-3 (pb)

This work reinterprets the Muslim architecture and urban planning of South India, looking beyond the Deccan to the regions of Tamil Nadu and Kerala – the historic costs of Coromandel and Malabar. For the first time comprehensive survey of the Muslim monuments of the historic ports and towns demonstrates a rich and diverse architectural tradition entirely independent from the better known architecture of North India and the Deccan sultanates.

The roots of the traditions of the South Indian Muslims are investigated through the history and culture of the maritime trading communities settled all along on the coasts of India since at least the tenth century AD and a large number of epitaphs and inscriptions on the monuments are analysed to establish the historical context.

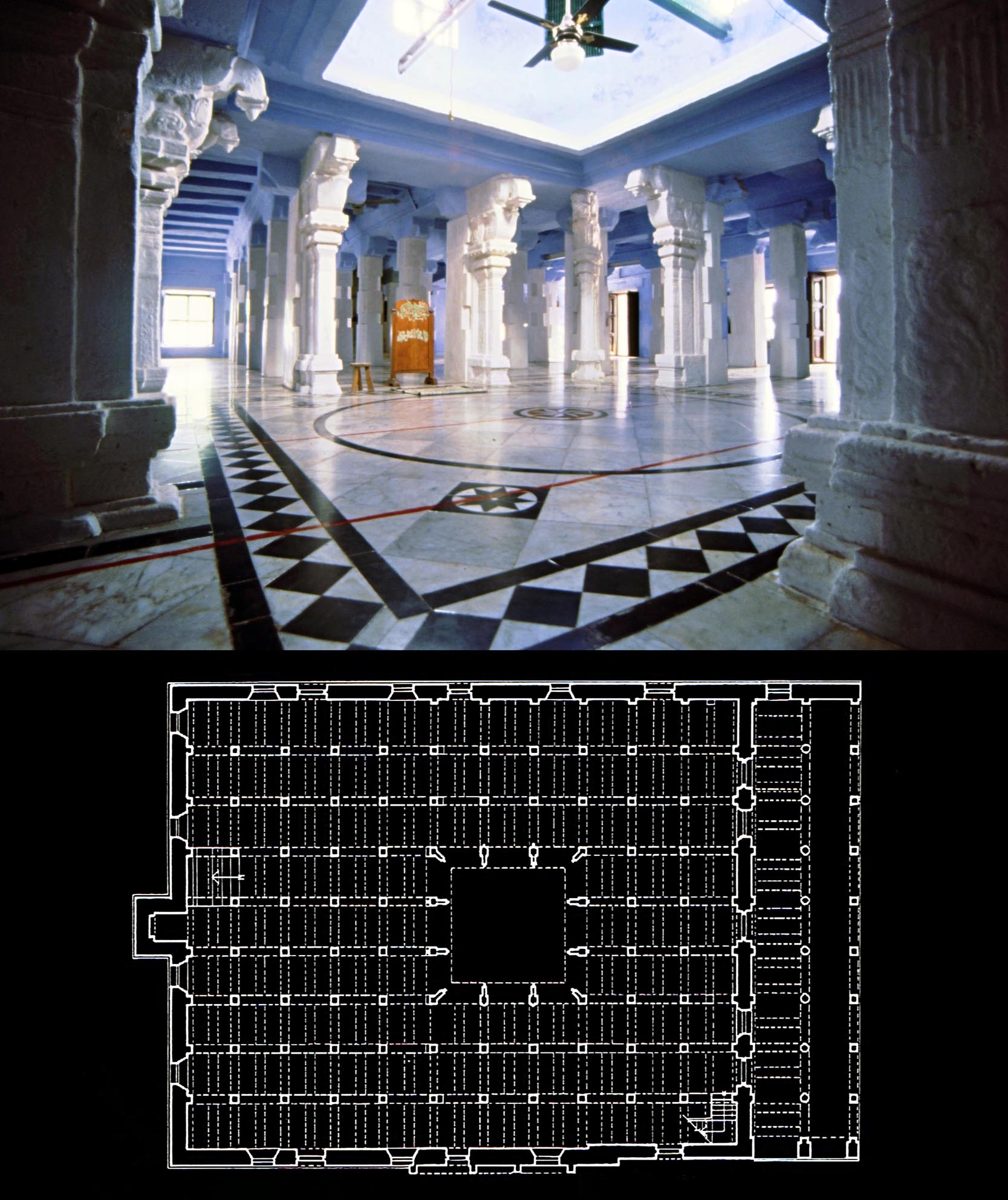

Kayalpatnam, the historic port of Qa’il, an interior view of the Khutba Parriapalli or Jami` al-kabir, the larger congregational mosque of the town, built in AH 737 (AD 1336-7) according to an inscription installed later. The square space in the centre was once an impluvium.

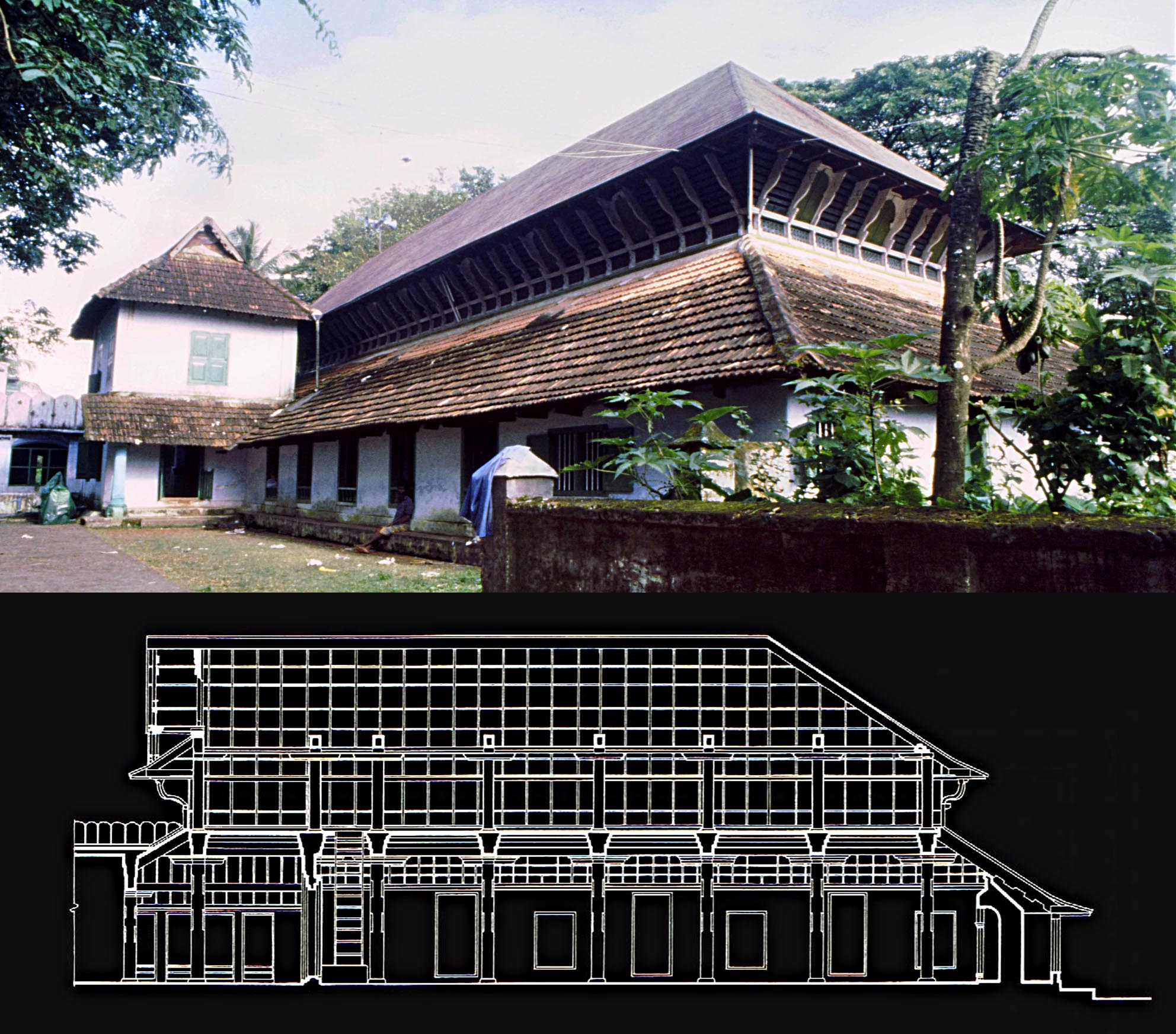

The journey begins in Gujarat with a brief introduction to the mosques and shrines at Bhadresvar and Junagadh which predate the Islamic conquest of this region. Further south the focus in Malabar is on the towns of Cranganur, Calicut and Cochin. Their historic urban patterns are studied and the wooden mosques, unique in style in Indian Islamic architecture, are discussed in depth. On the Coromandel coast Kayalpatnam is identified as the historic port of Qa’il (Marco Polo’s Cail) and its historic monuments described. In the heart of Tamil Nadu the short-lived fourteenth century sultanate of Ma‘bar is investigated and its associated monuments in Madura and the nearby town of Tiruparangundram are studied.

The journey begins in Gujarat with a brief introduction to the mosques and shrines at Bhadresvar and Junagadh which predate the Islamic conquest of this region. Further south the focus in Malabar is on the towns of Cranganur, Calicut and Cochin. Their historic urban patterns are studied and the wooden mosques, unique in style in Indian Islamic architecture, are discussed in depth. On the Coromandel coast Kayalpatnam is identified as the historic port of Qa’il (Marco Polo’s Cail) and its historic monuments described. In the heart of Tamil Nadu the short-lived fourteenth century sultanate of Ma‘bar is investigated and its associated monuments in Madura and the nearby town of Tiruparangundram are studied.

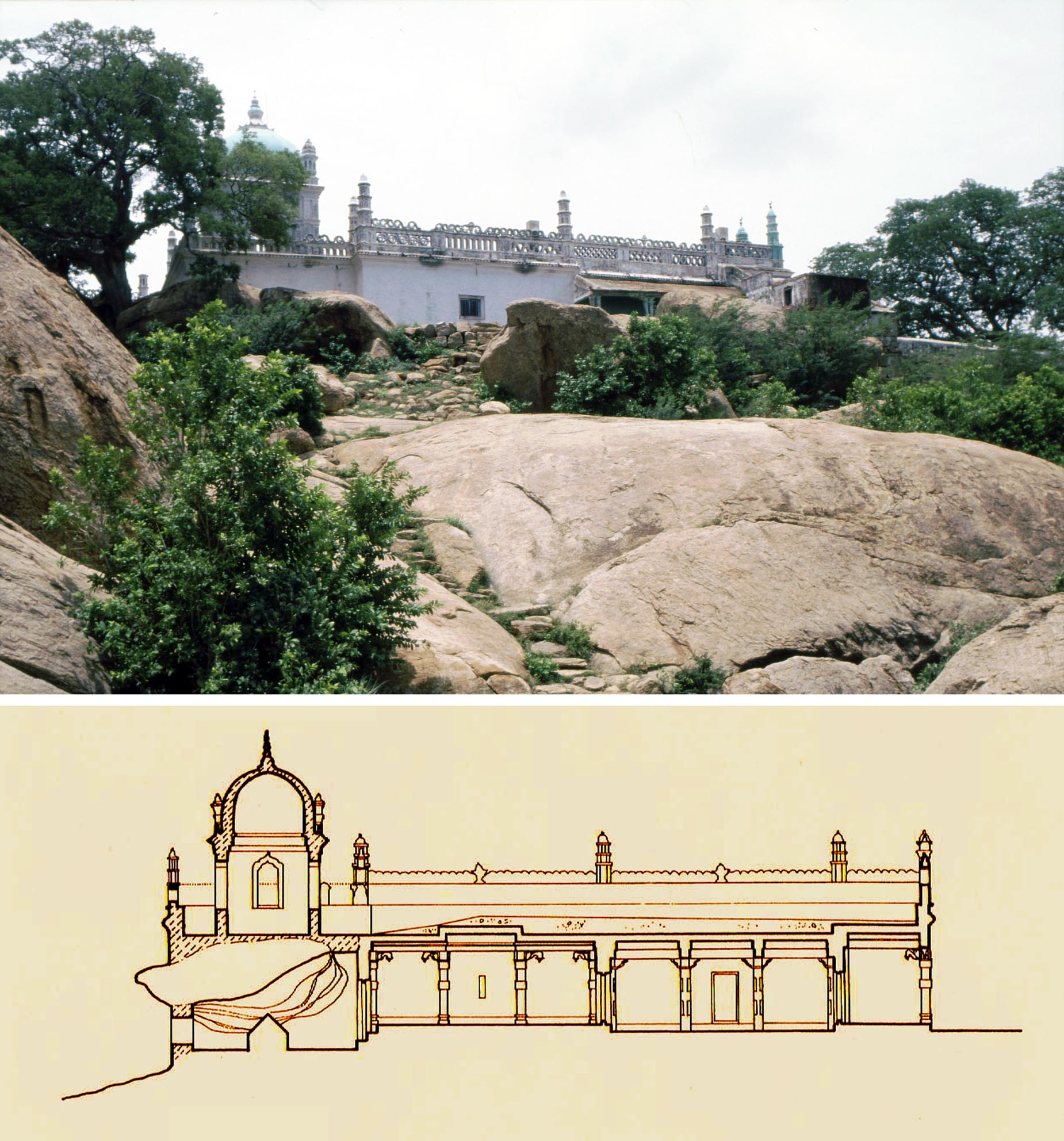

Tiruparangundram, tomb of the last Ma`bar sultan, Sikandar Shah,

who was slain together with his band of loyal troops by the mighty

Vijayanagar army. He was buried beneath a rock in the dramatic

setting where he fell and his tomb is now regarded by the local

Muslims as a shrine.

Photographs and architectural drawings illustrate the grandness of many of these monuments and the extent of the artistic achievements of these communities. Finally, in the light of the architectural vocabulary of the South Indian Muslims, two of the monuments associated with the sultanates of the Deccan are re-examined: the Safa Masjid in Ponda and the Jami‘ mosque of Gulbarga. These buildings represent the interface between the northern and southern traditions, but in earlier studies had often been misunderstood as the focus had been solely on the northern sultanates with little awareness of the architectural wealth of the maritime trading communities. The book widens the horizons of our understanding of Muslim India and has alerted the communities concerned and people in the wider maritime region to the importance of this heritage, as well as being a catalyst for new studies in the field.

Cochin, the Shafi`i Jami` or Chembattapalli, a fine specimen of traditional Malabar (Kerala) architecture, rebuilt in AD 1520 soon after the original building was burnt by the Portuguese.

The book is available in hardback and paperback from major booksellers and directly from Routledge at www.routledge.com. A Kindle edition is also available.

Tughluqabad, a paradigm for Indo-Islamic urban planning and its architectural components, M. and N. H. Shokoohy, (Monograph of the Society for South Asian Studies, British Academy) (Araxus) London, 2007, 266 pp., 95 drawings, 235 monochrome photographs, appendices, list, bibliography, index.

Tughluqabad, a paradigm for Indo-Islamic urban planning and its architectural components, M. and N. H. Shokoohy, (Monograph of the Society for South Asian Studies, British Academy) (Araxus) London, 2007, 266 pp., 95 drawings, 235 monochrome photographs, appendices, list, bibliography, index.

ISBN: 978-1-870606-10-3

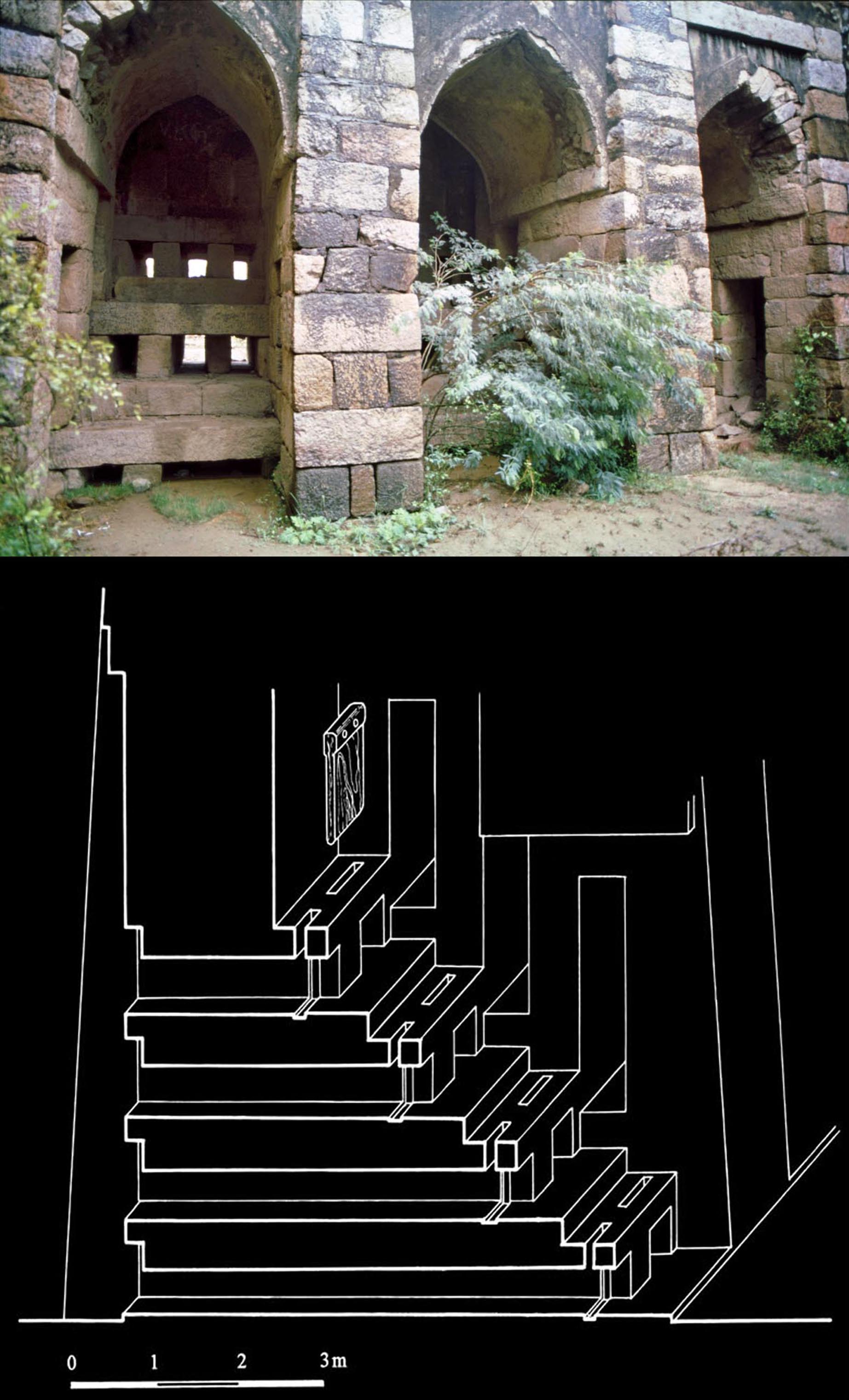

Tughluqabad Fort, the halls and apartments south of the public audience hall, probably used for the sultan’s more private meetings with courtiers and close companions as well as for retiring before and after great public events.

The historic town of Tughluqabad and its substantial lake is disappearing, being buried under the newly built houses of a less-privileged suburb of Delhi. During the twenty-four years of studying the site and seven seasons of fieldwork we witnessed the erosion of this very important historic heritage. Only the remains of Tughluqabad fort and citadel have been listed as Protected Monuments, but little has been done for the preservation of the town and the remains of its buildings. The town walls and major structures have become the source of building materials for rudimentary new houses on the historic site, while developers transform Tughluqabad into another suburb of the capital.

Tughluqabad, situated 15 kilometres south-east of the centre of New Delhi, is the oldest surviving sultanate town in India. Built by Sultan Ghiyath al-din Tughluq early in the fourteenth century, its towering walls, street layout and the remains of its buildings provide us with the earliest existing example of Indo-Muslim urban planning and its architectural components.

Tughluqabad, situated 15 kilometres south-east of the centre of New Delhi, is the oldest surviving sultanate town in India. Built by Sultan Ghiyath al-din Tughluq early in the fourteenth century, its towering walls, street layout and the remains of its buildings provide us with the earliest existing example of Indo-Muslim urban planning and its architectural components.

Tughluqabad is also unique from another point of view. Built in the first two years of the 1320s it had an unusually brief life, and within a generation was abandoned. Whatever is left of its layout and its monuments can, therefore, be dated to the early fourteenth century. The only minor interruptions were caused by a small settlement which remained as a village in the ruined town, and in the late Mughal period in the citadel. However, in spite of the proximity of Tughluqabad to Delhi, apart from the tomb of the sultan, the town itself and the monuments in its fort and citadel remained unstudied prior to our project.

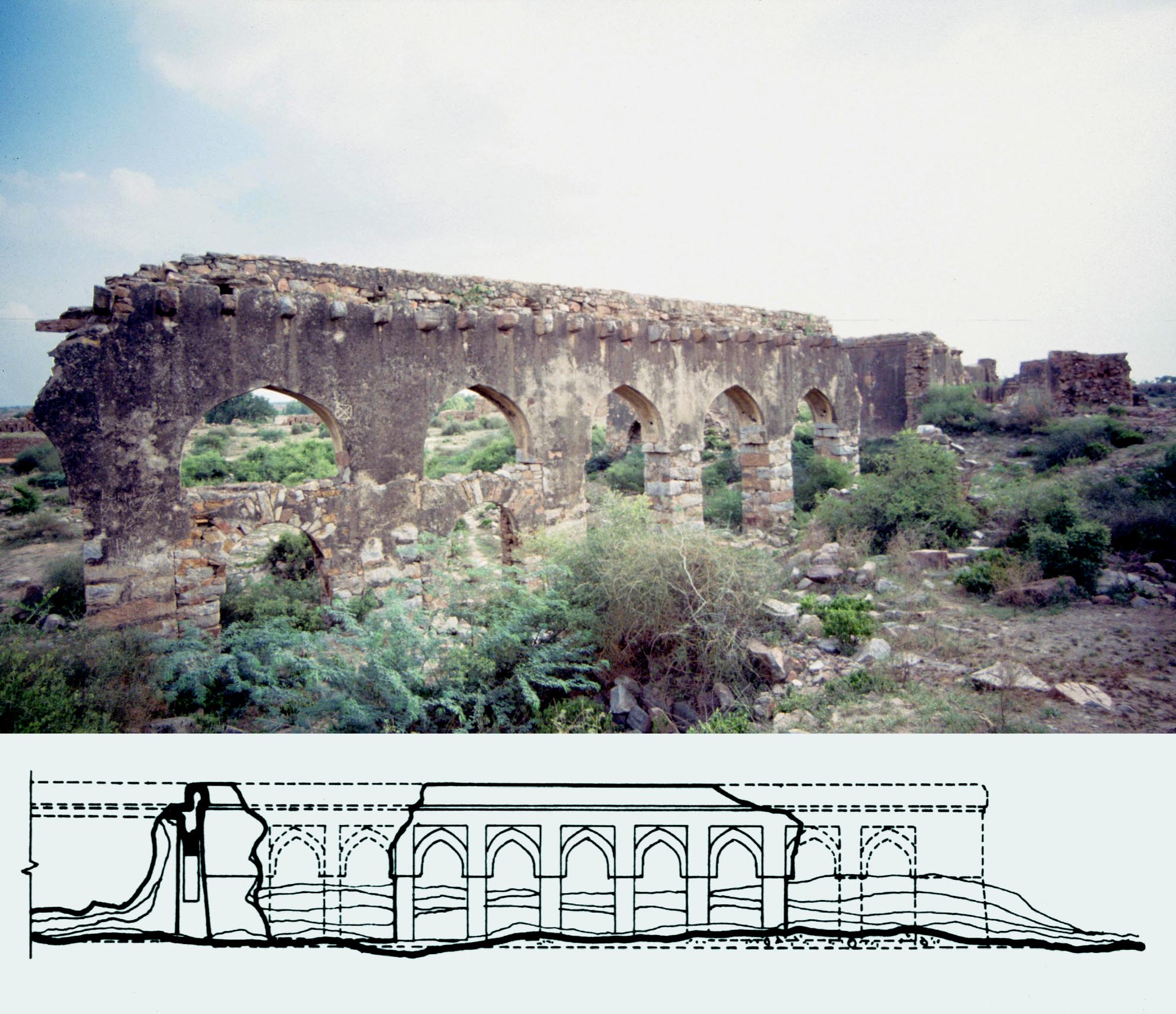

The ruins of Tughluqabad’s congregational (Jami`) mosque before it

was demolished, still preserving most of the original layout and enough

of the walls to provide information on the location and size of windows,

as well as the bases of the domes. A digital reconstruction of the structure

was produced based on the standing remains.

The book quotes and analyses the historical accounts related to the construction of the town, its short life and its final fate. The design of the town, and the way it was constructed in a period of about two and a half years is explained and surviving features of the citadel which housed the private palaces, the fort with the substantial interconnected public buildings and audience halls and the town with its street layout, bazaars and private houses are discussed in detail. A theological college (madrasa) and the grand mosque of Tughluqabad, both demolished along with many other buildings while our fieldwork was being carried out, are studied and a three-dimensional digital reconstruction of the mosque presented. Other reconstruction drawings of the buildings in the citadel and the audience halls also give an impression of the grandiose quality of Ghiyath al-din Tughluq’s palaces which Ibn Battuta describes:

“Tughluq’s treasury and palaces are located there, and in it is the greatest palace, covered with golden bricks, which when the sun shines reflect dazzling light, preventing the eyes from looking at it for long. He concealed great wealth in its treasuries, and it is said that he built there a cistern and filled it with gold, and all of that was spent by [his son] Muhammad Shah when he came to power.”

“Tughluq’s treasury and palaces are located there, and in it is the greatest palace, covered with golden bricks, which when the sun shines reflect dazzling light, preventing the eyes from looking at it for long. He concealed great wealth in its treasuries, and it is said that he built there a cistern and filled it with gold, and all of that was spent by [his son] Muhammad Shah when he came to power.”

The book ends with three appendices on the auxiliary sites outside the town: the lake and its waterworks, the tomb of Ghiyath al-din and the fort of `Adilabad.

The ingenious and unusual sluice gate of the Tughluqabad lake, designed in a manner that a single person, without the aid of machinery or animal power, could control the water level. The system, unparalleled in mediaeval times, appears to have continued to function for many generations after the town was abandoned, as silt eventually accumulated up to the highest level of the apertures of the sluices.

Available from major booksellers or directly from www. araxus.org, e-mail: sales @araxus.org

Street Shrines of Kirtipur, as long as the sun and moon endure, M. and N. H. Shokoohy and Sukra Sagar Shrestha (Araxus), London, 2014, pp. 440, with 168 colour and 320 monochrome illustrations, 9 maps and 11 diagrams, appendices, glossary, bibliography, index.

Street Shrines of Kirtipur, as long as the sun and moon endure, M. and N. H. Shokoohy and Sukra Sagar Shrestha (Araxus), London, 2014, pp. 440, with 168 colour and 320 monochrome illustrations, 9 maps and 11 diagrams, appendices, glossary, bibliography, index.

ISBN: 978 1 870606 11 0

Miniature stupa or chibhha and its associated mandala at Mvana Tol. As with all shrines it is more than an identifier or an urban node, being the object of daily worship by the residents of the close-knit neighbourhood, as well as for other townspeople passing by, particularly during religious processions, which incorporate particular shrines en route. The urban space around the shrine is used for farming operations such as drying grain, and for everyday activities like hanging out laundry.

A main feature of the towns of the Kathmandu Valley is their street shrines, Hindu, Buddhist and aniconic. These small shrines are not just the nodes of their environment, but distinguish and characterise the neighbourhood. They express the desire of ordinary townspeople to commemorate their faith and presence in a tangible way rather than being public manifestations of piety expressed by rulers and high ranking officials in the building of major temples or religious structures.

Our earlier study of Kirtipur considered the town as a whole, with emphasis on the use of public and private space, focusing on the urban form and survey of the major religious buildings, temples, stupas and monasteries as well as dwellings. The street shrines were also mentioned in association with larger monuments and some examples were illustrated, but it was clear that a thorough study of the shrines would require a volume of its own.

Istachoni Mahakala shine built of stone in the

form of a miniature temple, with the roof

imitating a wooden tiered roof. An aniconic hole

in a stone set in the floor represents the deity,

and people from the surrounding area make an

offering here of the first milk given by their

domestic animals after the birth of a calf or a kid.

The Ganesh Shrine at Singhaduval, an important stopping point on processional routes, built originally in the sixteenth to seventeenth century in the traditional style and photographed in 1986. It was demolished a few years later and replaced by a concrete structure of no architectural merit, incorporating only some of the original carved elements.

It is ironic that in spite of the prevalence of shrines in the public and semi-public space in every town of the Valley, they have never been studied in a systematic way. The shrines exist where they would be expected and are so much part of everyday life that every detail about them is perceived to be known. This sense is reinforced by a superficial similarity between various types of Hindu shrine, those dedicated to Ganesh for example. Buddhist shrines, particularly the miniature stupas, also follow an instantly recognisable configuration. However, when looked at closely, no two shrines are exactly the same – each offer certain individual characteristics and many are of intrinsic artistic value. In addition, apart from artistic value, each shrine bears the marks of its own relationship with its immediate urban space, and together the shrines reflect the history and the social life of the town.

In 1995 a project for studying the street shrines of the town was set up at the University of Greenwich, jointly with Sukra Sagar Shrestha, a resident of Kirtipur and former Chief Archaeologist at the Department of Archaeology of the Government of Nepal, with the aim of providing a full record of the shrines. In many cases the shrines incorporate a number of images or features, each of which is given individual attention.

In 1995 a project for studying the street shrines of the town was set up at the University of Greenwich, jointly with Sukra Sagar Shrestha, a resident of Kirtipur and former Chief Archaeologist at the Department of Archaeology of the Government of Nepal, with the aim of providing a full record of the shrines. In many cases the shrines incorporate a number of images or features, each of which is given individual attention.

Gachhen hiti, a natural spring which as with other springs, is regarded as a shrine and has its water spout carved in the form of makara, a mythical water creature. The icon of Lakshmi and Narayana, once set over the waterspout and seen in this 1996 photograph, has since been stolen and its present whereabouts are unknown.

Field-work was carried out in three seasons in 1996, 1999, and 2004 and Sukra Sagar Shrestha apart from contributing to the study also provided impressions and transcripts of the inscriptions associated with the shrines. This exhaustive work, illustrated with numerous colour and monochrome photographs considers every item in the shrines from the earliest dates to the end of the twentieth century, with a few examples set up in the first decade of this era, demonstrating the continuity of the tradition.

Available from major booksellers or directly from www. araxus.org, e-mail: sales @araxus.org